Socky Pitargue’s subversive brush

Painter Socky Pitargue recently exhibited at the Freedom Factory in Toronto. INQUIRER/Patty Rivera

TORONTO—It’s been less than a decade since artist Socky Pitargue left Manila and set foot in Toronto. Yet in that narrow span of years she has managed to set her goals and work on them one step at a time.

Of course, goal-setting was nothing new to her. It came with her job as vice president and executive director at J. Walter Thompson (now Wunderman Thompson), and as founder of her own ad agency, PC&V Communications, which she set up in 1997.

Toronto, “Where there are trees standing in the water,” from a Mohawk word “tkaronto,” became home because her partner had moved here, and she had followed soon after.

Masarap!Steytsayd!/Socky Pitargue

Freed from agency life, Pitargue had plenty of time in her hands. She checked out her options and decided to pursue the one avocation she thought was beyond her: to be a maker, instead of a viewer of art. In no time, she picked up the brush. That was four years ago and she has not put it down since.

And like the wunderwoman that she is to clients and friends, Pitargue taught herself to paint, not just in one, but in various media: acrylic; digital; printmaking.

Even in her choice of subject matter or theme, Pitargue goes against the grain.

Subversion and political and social action permeate her work; they comment and pick on the various aspects of contemporary culture and social givens whether in her home country or in her adopted land. She accomplishes this through energetic figurative works that put to life Elaine de Kooning’s perspective on art, or painting as primarily a verb, not a noun.

Ang Mga Babaeng Nanlaban/Socky Pitargue

Her artist’s statement sheds light on a cultural upbringing that blends the old and the new from her past and current historiography: “Her point of view comes from her identity as a person of color, female and gay. She explores themes of the Philippines’ colonial past, bringing to life what more than 400 years of Spanish and American colonization look like.”

She paints a lot of women in colonial dress, whether they’re from the cacique class or the indentured class. They figure prominently in her canvas, whether they are holding a beaded rosary or clasping a revolver (“Ang Mga Babaeng Nanlaban”) instead of the ubiquitous pamaypay or fan.

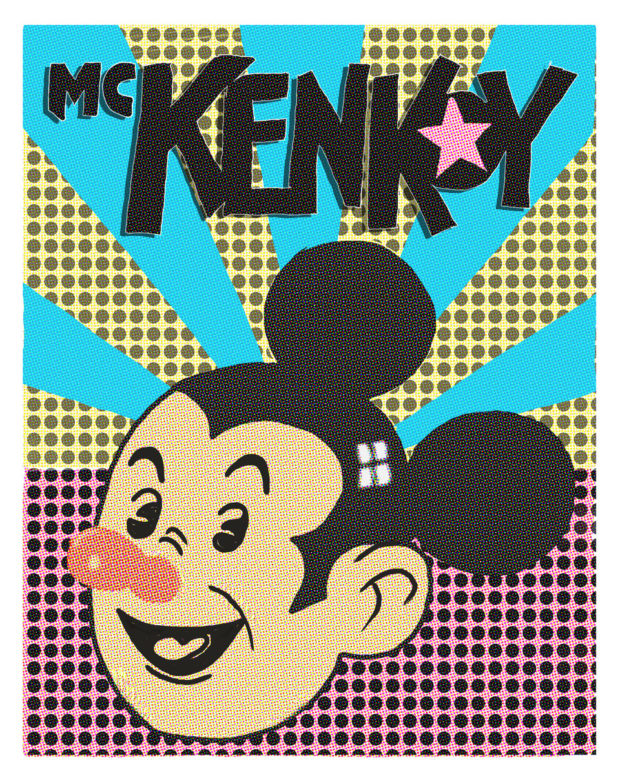

McKenkoy/Socky Pitargue

Worrying about gun violence in America? “We gat them plenty here,” is Pitargue’s tongue-in-cheek response. Filipino women “have got it” even the days before women’s lib.

Take a look at “Mahinhin Pero Maldita” (Modest But a Bitch).

Filipino artists have been known to use their art to provoke or to harangue. Whether in the social realist art of Juan Luna’s Spoliarium, 1884 (national hero Jose Rizal was known to have said that Juan Luna’s Spoliarium “embodied the essence of our social, moral and political life: humanity in severe ordeal, humanity unredeemed, reason and idealism in open struggle with prejudice, fanaticism and injustice”) to the cartoon characters that emerged from early American occupation, art has been employed to bring to the fore issues of class, social and economic inequality, and the misdeeds of political figures.

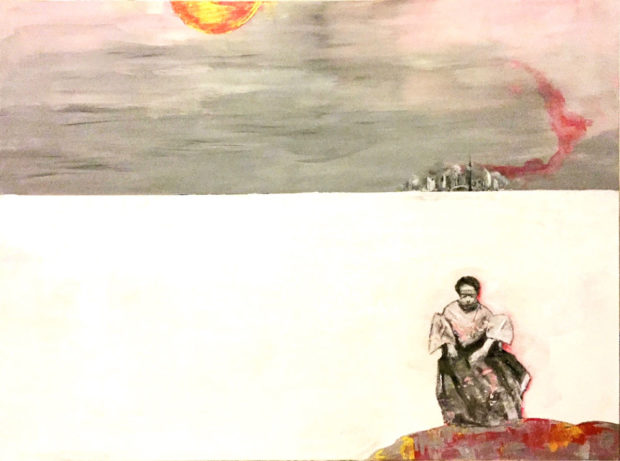

What We Left Behind/Socky Pitargue

Kenkoy, a comic character who was introduced to Filipino vernacular magazine readers in 1929 (or a year before Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse), satirized high society.

In her own way, Pitargue takes a cue from this iconic symbol by caricaturing the Filipinos’ love of the Stateside by placing Kenkoy with an image of that famed canned luncheon meat also known to Western connoisseurs as Spam (“Masarap…Isteytsayd!”). To Filipinos at home and to expats here, Spam meets Kenkoy is even a livelier rendition than Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans.

Thus in her work, Pitargue emphasizes themes of consumerism, popular culture, politics, gender and identity. She challenges rigid perceptions of fine art by using the common and the popular—from the Ben Day dots in “McKenkoy” to denote gradients and texture much like the way pop artists did in the 1960s, to the erasure of paint to show the veins of color underneath.

Mahinhin Pero Maldita/Socky Pitargue

Echoing Rauschenberg’s take on erasing a De Kooning painting to draw his own over it (“I put my trust in the materials that confront me, because they put me in touch with the unknown”), Pitargue experiments with erasing her own already-drawn canvas to discover images previously hidden.

In an exhibit at the Freedom Factory in Toronto, Pitargue documents not only her art journey, but also describes the diasporic experience and point of view, and hopefully, provokes thought, contrary opinion, and discussion.

She hopes to tell the journey story with the shape and images she conjures—from the playful to the whimsical, from the mundane to the ethereal.