The cassette recording begins with a simple greeting: “To Nonoy, on your fifth birthday from Tatay and Nanay.”

Edgar and Joy Jopson were living underground in Mindanao when they made the tape for their son, Noy, in 1980. This was a time before cell phones and digital media, and sending letters and audio recordings were the only ways to keep in touch with him.

On the 20-minute recording, they sing activist songs and ask how he is doing in school. They tell him stories of life in the resistance with ordinary Filipinos who bore the brunt of the dictatorship’s cruelty.

“We are still living in a probinsya, but it’s different from the place you visited before,” Edjop says.

“Here we also have a lot of good friends, the poor, the masa. Ordinary people. They are good to us. They share their food, their blankets, their pillows, with us. They let us stay in their houses. They help us in many ways. When you come here, we will introduce you to them.”

Noy never got the chance to meet the ordinary people Edjop was fighting for and who in turn embraced and welcomed his Tatay and Nanay to their communities. Edjop was killed in a military raid in Davao two years after they recorded the message.

The recording was one of the most emotionally compelling materials I worked with when I wrote Edjop, The Unusual Journey of Edgar Jopson, which came out in 1989.

I was 25, young and single, when I made my first attempt to trace Edjop’s dramatic journey.

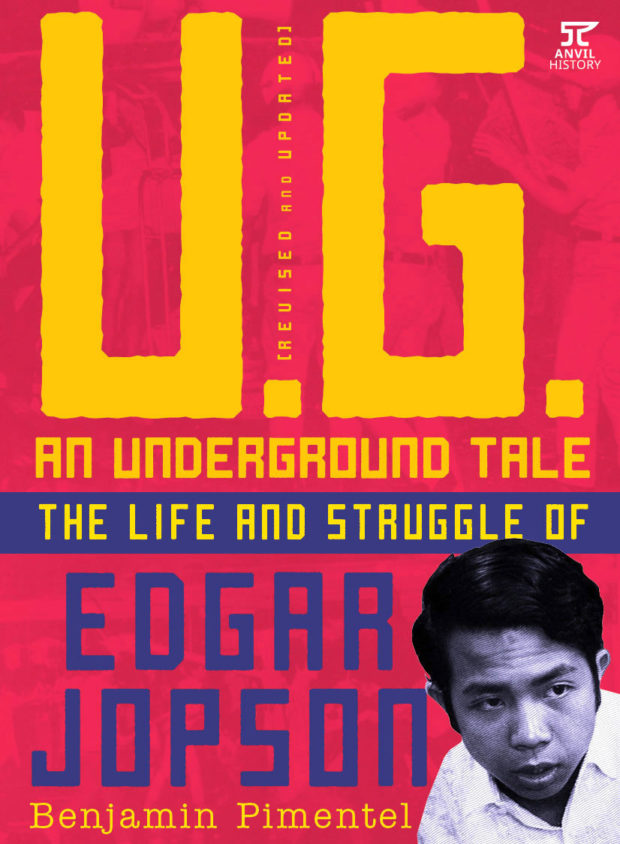

Edjop was later re-published in 1991 in New York by Monthly Review with the new title, Rebolusyon, A Generation of Struggle in the Philippines. More than a decade later, I saw the need to tell a more complete story which led to U.G., An Underground Tale which was published by Anvil in 2006.

Re-telling Edjop’s story led me again to the audio cassette that he and Joy sent to Noy on his fifth birthday. It was a tougher listen that time around.

As I heard Edjop’s voice again, I felt a tightness in my chest and choked up. I had to stop playing the tape a few times.

I was then 42, eight years older than Edjop when he was killed. By then, too, I was a parent with two young sons. Suddenly, the magnitude of Edjop’s sacrifice became clearer, more daunting.

When U.G. An Underground Tale went out of print a couple of years ago, I felt that a new edition was in order and Anvil Editor Ani Habulan readily agreed.

The timing is perfect, which is sad in a way. This new edition of U.G. An Underground Tale comes out at a time when Edgar Jopson’s story has become even more compelling for me and I suspect for many Filipinos.

Once again, the Philippines is in darkness, reeling from repression, abuse and fear.

In 2017, the dictator Edjop sacrificed everything to defeat was proclaimed a hero. This disgraceful act was endorsed by a leader who has inspired a horrifying mass slaughter, who routinely bullies his opponents, and who has shown brazen disrespect for women, the poor, for anyone who dares to criticize and oppose the bloodbath he unleashed.

In 2018, the dictator’s daughter, Imee Marcos declared, “The millennials have moved on, and I think people my age should also move on as well.” Translation: forget the past, forget the plunder, the torture, the murder and the abuse.

Edjop would have turned 70 in 2018. He was 34 when he was killed by Ferdinand Marcos’s military.

He “moved on” decades ago, though not in the way Imee Marcos would want Filipinos to move on today. Edjop was in his early 20s when he moved on from the prosperous, safe, secure future young Filipinos of his generation and class always felt entitled to in order to join the fight against a tyrant. He didn’t have to give a damn about the plunder, the torture, the abuse.

But he did.

One thing is clear: Edjop’s story, his sacrifice and journey of courage, resonates with many young Filipinos. Thirty-six years after his death. Edgar Jopson’s journey still inspires.

This new edition of U.G. An Underground Tale includes a moving essay by Edjop’s daughters. Joyette, now an accomplished triathlete, was about to run in the North Pole Marathon, the first Filipina to do so, when I asked if she could share her reflections on the race and her father’s incredible journey.

She went on to write a moving essay that became part of UG.

“There are things for which I am truly grateful to my parents,”Joyette writes. “From Tats: You lived your best life, even if it was short From Nanay: You taught me to not be afraid to stand up for myself. And that while there is life, there is hope … and to keep fighting for what is right.”

Risa was five months old when his Tatay was killed. She grew up meeting people who knew of and were inspired by Edjop’s story. “One morning in fifth grade, my homeroom teacher took me to one side of the room next to a large open window and told me that my father was a hero. I was stunned that my favorite teacher, who was neither a relative nor a friend, would know of my father, and maybe even better than I did.”

This edition of UG also includes two essays by young Filipinos who never knew Edjop but who were both moved by his story.

Lawyer and Philippine Daily Inquirer columnist Oscar Franklin Tan had just turned three when Edjop died. I got to know him after he reached out to share how U.G. An Underground Tale influenced his understanding of the past.

“U.G. allows us to intimately picture how a youth just like us struggled against the Philippines’ descent into chaos,” he writes. “U.G. empowers us to believe that should martial law return, our generation can stand equally ready to defend our democracy.

“When deposed President Ferdinand Marcos was buried in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, it was young Filipinos not yet born during martial law who led the protests. Today’s youth know how to search for history and harness its power.”

Oscar is right about the Filipino youth. I was surfing the web one day when I came across a blog post in the form of a letter written by another young man I didn’t know. It was addressed to his friend, Joyette Jopson, Edjop’s daughter. Rey Agapay was also three when Edjop was killed.

“I just finished reading your father’s biography, U.G., An Underground Tale,” he tells Joyette. “I bought the book a few months back but never got to read it, but when I started I couldn’t put it down.

“Gusto ko lang sabihin sa’yo na idol ko ang tatay mo, ang nanay mo, ikaw, at ang buong pamilya n’yo. Before reading the book, I was only vaguely familiar with your father’s martyrdom, kaya mas lalo akong napabilib at namangha nang mabasa ko na ang kuwento niya. …. I’ve always felt that I owe a lot to your father’s generation, kasi sila talaga ‘yung nag-sacrifice ng normal na pamumuhay para lang makapag-aral ako sa UP nang hindi nahihinto dahil may diktaturyang kailangang kalabanin. Dahil isinantabi ng tatay mo ang komportableng buhay, at isang financially rewarding career path, walang gaanong guilt kong magugugol ang mga panahon ko para matupad ang mga personal kong pangarap.”

As I first read Rey’s letter, I quickly became familiar with the sense of gratitude — utang na loob — to a person and a generation who sacrificed everything for other future generations. For that was also how I felt when I began exploring Edjop’s remarkable journey.

The tale of Edgar Jopson has been part of my consciousness for 30 years now. I simply can’t let it go. I simply can’t get Edjop’s story out of my head and heart.

(UG An Underground Tale is available at Anvil Publishing and National Book Store branches. Royalties from this edition of UG An Underground Tale will go to the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani which has done an incredible job documenting and honoring the contributions of those who led and joined the fight against the Marcos dictatorship.)

Visit the Kuwento page on Facebook.