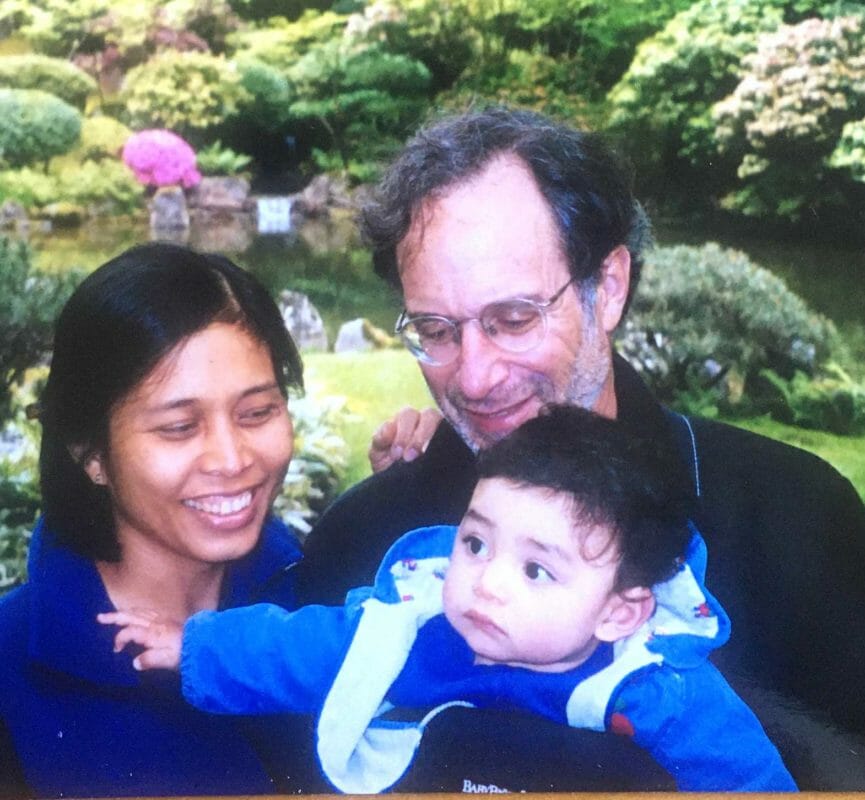

The late thinker Jonathan Rowe with his wife, Mary Jean Espulgar, and their son, Joshua. ROWE FAMILY

In December 2008, I got an email from a radio host in Point Reyes Station, a small town north of San Francisco, inviting me to be a guest on his program.

Jonathan Rowe wanted to have a conversation about “Pareng Barack: Filipinos in Obama’s America,” my then newly-published book about what Barack Obama’s victory could mean for Filipinos.

I had not heard of Jonathan before that email. But I eventually realized what a big deal it was to be invited by someone like him.

Jonathan Rowe was a highly-respected journalist, activist and political thinker, best known for his inspiring advocacy for “the commons,” a worldview that seeks to give people the opportunities and power to share, nurture and defend their community resources.

Sadly, I got to know him only briefly. Jonathan died unexpectedly in March 2011.

But I recently found myself revisiting our brief friendship, reflecting on his ideas and their relevance in today’s world. I went back to our email exchanges, and to a recording of our live radio chat. The 55-minute conversation — which you can check out on Jonathan’s website — took place on December 30, 2008.

The date is significant for me personally. It marked the end of what had been an incredible year for the United States, and a happy, exuberant one for me and my family.

In November 2008, my wife, Mara, and I celebrated with our young sons the election of the first Black U.S. president, a brilliant, progressive leader who won with broad support at a time when many Americans were reeling from a severe financial crisis.

A few weeks after Obama was elected, I returned to the Philippines to launch “Pareng Barack” which I managed to write at breakneck speed, inspired by what Mara and I saw as an important milestone in the story of America. I was also in Manila to watch the stage adaptation by Tanghalang Pilipino of my novel “Mga Gerilya sa Powell Street,” which during my visit also won the National Book Award for fiction.

I had just returned from Manila, ecstatic, upbeat and optimistic about the future, and was celebrating the holidays and a new chapter in America’s history with Mara and our two boys, when I got Jonathan’s email. I readily accepted his invitation for a conversation, which turned out to be a perfect ending to an uplifting year.

Jonathan was a thoughtful, engaging interviewer, a good listener who genuinely cared about people, their stories and their communities. Listening to that interview 13 years later made me regret even more that he’s gone and that the world didn’t get a chance to read and listen to more of his ideas.

(It was also somewhat strange to listen to my 44-year-old self expressing optimism about the state of the world. This was, after all, before the era of Dutertismo and Trumpism, before the U.S. and the Philippines began reeling from an era of hate, violence and intolerance.)

That December, Jonathan and I also talked about a topic that he clearly was increasingly interested in: the Philippines.

“My wife is from Iloilo, and so I have an interest in the Pinoy side of things,” he had said in his email inviting me, referring to Mary Jean Espulgar Rowe. We talked a lot about his own effort to understand our history and culture. In fact, the Philippines helped inform his own ideas for the commons and the importance of community.

“My wife grew up in what Western experts, without condescension, call a ‘developing’ country,” Jonathan began his book “Our Common Wealth” which was published in 2013, two years after his death. “The social life of her village revolved largely around a tree. … The tree was more than a quaint meeting place; it was an economic asset in the root sense of that word. It produced a bonding of neighbors, an information network, an activity center for kids, and a bridge between generations.”

What Jonathan hoped to accomplish, his friend Bill McKibben wrote in the book’s foreword, was “to revivify a whole spectrum of human activity that was small, local and mostly nonmonetary. He knew such activity was widespread, but it didn’t have a name. After much thought, he stuck an old appropriate tag on it: ‘the commons.’ Once he took this leap, a whole world opened up.”

In the short time that I got to know him, Jonathan came across as a kind-hearted, soft-spoken writer and thinker with big, bold ideas who had influenced a great many people. Writer James Fallows, in a tribute after Jonathan’s death, described him as “so modest, gentle and understated in personal bearing that he was not as well-known as he could have been.”

Activist and writer David Bollier expressed a similar point: “Jonathan never acquired the recognition that he deserved as an original thinker and venturesome journalist. It’s partly because he deliberately chose to live outside of the constellations of prestige and respectability, and outside of the power centers of New York and Washington, D.C. He knew that the really important, transformative ideas would not emerge from there.”

Instead, Jonathan explored and developed his ideas about the commons in a small, quaint down in the San Francisco Bay Area. Point Reyes Station (population 350) where Jonathan lived with Mary Jean Espulgar and their son Joshua is a scenic community south of Tomales Bay, near the Point Reyes National Seashore.

It’s a beautiful place that Mara and I had always enjoyed visiting with our sons. A few months after our interview, I asked Jonathan for some suggestions for inns where we could stay.

He surprised me with an offer: why not stay at their house when they were out on a trip? It was a generous gesture which I have never forgotten.

Mara, our sons and I had a wonderful time during our stay. There was even a bonus for our boys who got to enjoy playing with Joshua’s Star Wars toy collection. “Next time, come when Josh is here. He would take great pleasure in playing Star Wars legos with other passionate fans,” Jonathan said in an email after our visit. (Sadly, we never got a chance for a second visit, and to meet Mary and Joshua at their Point Reyes home.)

Jonathan and I exchanged emails throughout most of 2009 on a range of topics, including his own experiences visiting the Philippines.

One comment underlined his respect for community and tradition, which clearly was rooted in his faith in the commons, and his critical view of “development” as defined by the West.

Visiting the Philippines can be challenging, he acknowledged. “I would get a little dizzy,” he said in an email. “There was no order. And yet things functioned, more or less. It is still a riddle. Perhaps part of the answer for the country is to stop trying to be like the U.S., and to find a way to ride that indigenous chaotic energy.”

When a big typhoon caused much damage in the Philippines in late 2009, Jonathan reached out to ask if I knew of relief efforts worth supporting.

In March 2011, he emailed to ask if he could contribute articles to the INQUIRER. I said to send me the article so I can forward it to the editor for contributions. That was our last exchange.

Five days after those emails, Jonathan became ill suddenly, developed a high fever and died at the hospital. Because I was not part of his close network of friends, I didn’t hear immediately of his death. I only found out three years later when I came across an article about his passing.

I went over our old emails recently which prompted me to reach out to Mary Jean. She has moved to Washington, DC, where Joshua is now a college sophomore at George Washington University.

“The funny and touching thing about Jon, though, was his almost complete lack of interest in personal glory,” Paul Glastris, editor of the Washington Monthly, wrote in another tribute. “I have never worked with someone — certainly no writer — more genuinely humble and self-effacing. He was unfailingly kind, with an unmistakable inner light — he was a man of faith, though he almost never talked about it. He spoke with a gentleness bordering on diffidence, but also with a winning twinkle of humor.”

I came across that humor after our December 2008 conversation, in which he struggled with a few words in Filipino. He had a particularly tough time pronouncing “Pareng” in “Pareng Barack,” derived from “pare,” which means buddy, pal or friend in Filipino.

“Wonderful show,” Jonathan said in an email. “My apologies for mangling Tagalog. My wife’s dialect is Kari-ya, which is a version of Ilonggo, and I don’t hear Tagalog that much… not that I’d do much better in Kari-ya.”

It is now my turn to apologize … for this tribute to a friend is 10 years late.

Farewell and thank you, Jonathan Rowe. Paalam at maraming salamat, Pareng Jon.