Marcos’ personal priest: ‘He was betrayed by his own people, like Jesus Christ’

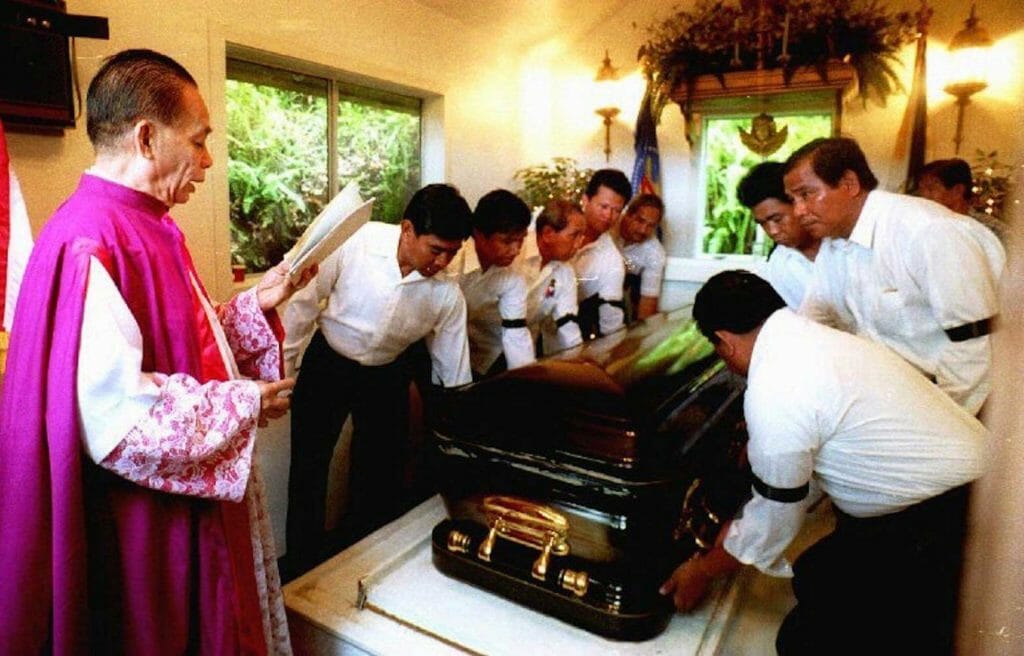

Monsignor Domingo Nebres (L) reads his benediction in Hawaii as the body of the late Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos is removed 01 September 1993 from the mausoleum where he lay in state since dying in exile in 1989. Marcos’ body is scheduled to be returned to the Philippines on 05 September. GEORGE LEE/AFP

In Manila, President Ferdinand E. Marcos hid his serious sickness from the people, when he was already suffering from Lupus erythematosus, a degenerative kidney disorder that spread inflammation to his other vital organs.

In his exile, he underwent two kidney transplants, all done in secrets. He also suffered from heart and lung ailments, pneumonia, and deadly bacterial infections. In September 1989, Marcos died in Hawaii, more than 6,000 kilometers from his homeland.

His death provided the final chapter of a presidential life marked by plunder and deceit that, when he was hospitalized in January 1989 at St. Francis Medical Center in Honolulu, his political foes suspected that his hospitalization was a tactic to avoid having to testify before the United States courts in an attempt at recovering his ill-gotten wealth.

It must be recalled that the United States Customs agents seized secured documents and official bank notes from the Marcoses upon their arrival in Honolulu in February 1986. Those papers, added to the documents left behind in Malacañan Palace, revealed the extent of kleptocracy and the plunder of public funds.

He died a Catholic and his remains were brought to Hawaii’s largest church, the Co-Cathedral of St. Theresa in Honolulu. At the funeral service, Mrs. Imelda Marcos recited the Lord’s Prayer and BBM, Ferdinand E. Marcos’ only son and namesake, delivered a eulogy to his father.

On that solemn occasion for the departed, something untoward happened. Before his final blessing, Monsignor Domingo Nebres insisted that Marcos was similar to Jesus Christ, who “was a victim of the People Power.”

Those in attendance were pleased after he likened Marcos to Jesus, a Savior betrayed. However, what he said totally shocked the Catholic world. In Msgr. Nebres’ opinion, the Ilocano dictator was a redeemer of a nation stabbed by disloyalty, a leader “betrayed by his own people, like Jesus Christ.”

Bishop Joseph Ferrario of Honolulu heard about the untoward incident, as The New York Times reported. Naturally, the good bishop reacted and issued a formal statement denouncing the Filipino priest’s remarks as “ridiculous, absurd, and an insult to the Filipino people.”

Apparently, the local conservative Catholic diocese in Honolulu did not like the Marcoses, who caused a stir in their peaceful neighborhood by drawing much press and public attention whenever certain Catholic Filipino priests celebrated Masses for the family. In Honolulu, in 1986, the family with their supporters organized an Easter service which drew much hullabaloo because of its political undertones.

Msgr. Nebres was the personal chaplain to Ferdinand E. Marcos in the same way as Fr. Pacifico Ortiz was to Manuel L. Quezon. While Quezon was the first president to die in office, Ferdinand Marcos was the first and only President to hold office for two decades (1965-1986), which could have been longer if EDSA Revolution didn’t happen. Monsignor Nebres was at the side of Marcos when he died as Ortiz was with the Commonwealth President when Quezon departed into eternal life.

Bear in mind that the two leaders died in the United States, one exalted and the other vilified. While in office, Quezon departed this life with his dignity intact and his name extolled. While in exile, President Marcos passed away with dignity shattered and his name was identified with the sickening corruption, militarization, and cronyism that made the Philippines the “Sick Man of Asia.”

When American investigative reporter Raymond Bonner wrote his book Waltzing with a Dictator in 1987 and when The Washington Post and The New York Times reported the exile, hospitalization, and death of the former Philippine president Ferdinand E. Marcos, Sr., they wrote it after the fact. These respected journalists reported the events not as perceived or supposed, but after they really happened.

In September 29, 1989, journalists Keith B. Richburg and William Branigin of The Washington Post recounted that all his life, Marcos projected himself a strongman, but he died without power and his 20-year regime became synonymous with greed and corruption. In Waltzing with a Dictator, Raymond Bonner wrote that Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Manila station chief Herbert Natzke once described Marcos as a brilliant man with two flaws: “He can’t avoid stealing everything in sight, and he can’t control his wife.”

Good historians and investigative authors are evidence-and-research-based writers, who refused to be consigned to the wastepaper bin of a revisionist history.

Jose Mario Bautista Maximiano (facebook.com/josemario.maximiano) is the author of THE BEGINNING AND THE END (Claretian, 2016) and 24 PLUS CONTEMPORARY PEOPLE: God Writing Straight with Twists and Turns (Claretian, 2019).