I wish my dad were a Filipino veteran of WWII.

Maybe he would have been a guerilla or Philippine Scout had he stayed in the Philippines.

But as fate would have it, he came to America in 1928, a colonial Filipino, an American national. He would ultimately be too old for WWII.

What happened to him in America before and after the war?

That’s the subject of my one-man show, my Amok Monologues: “All Pucked Up.” I’m in Baltimore, Maryland on the next two weekends at the Charm City Fringe Festival, get your tickets and say hello.

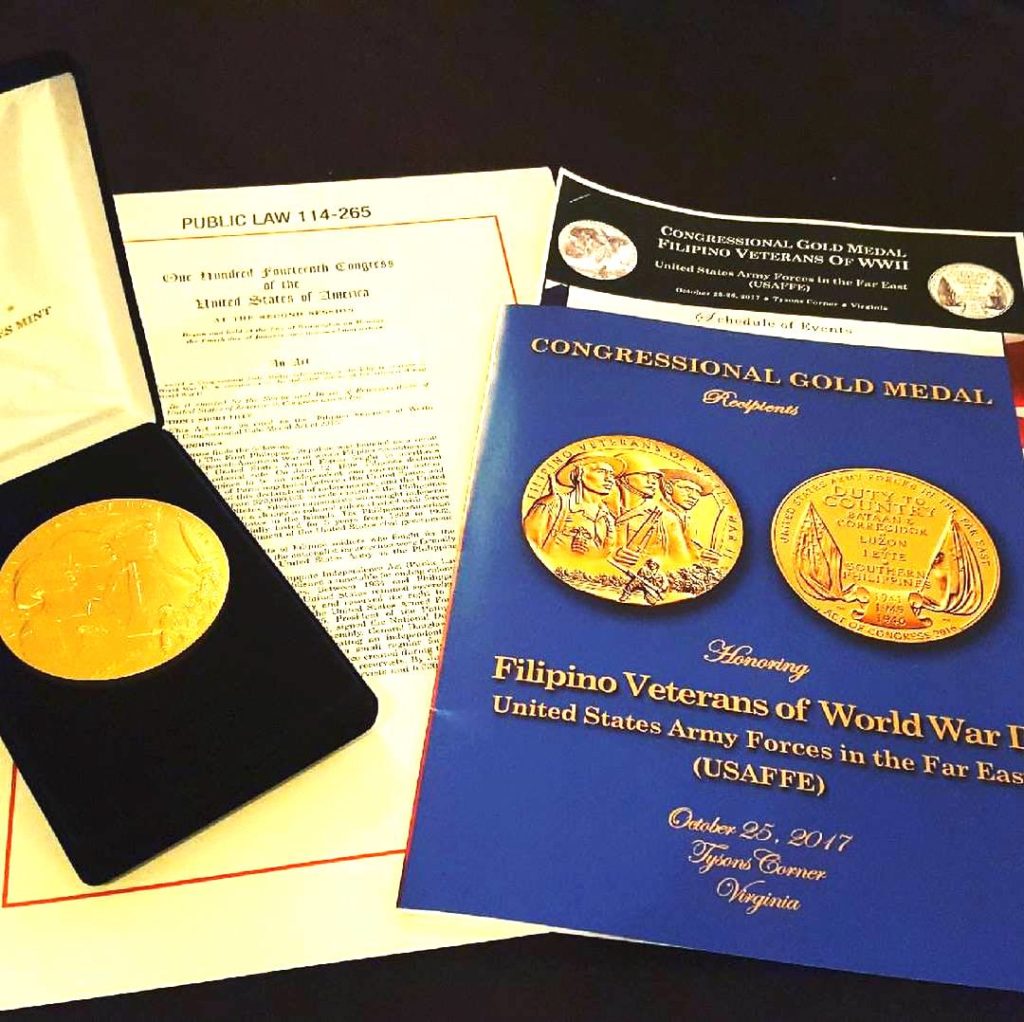

I know my dad would be proud of my Uncle Melecio Guillermo. At my dad’s urging, Uncle Mel came to America. He was younger, and he went to war. When Filipinos were drafted into the Army, he served proudly as a corporal, a recipient of a Purple Heart, and now a Congressional Gold Medal winner.

If like me, you couldn’t make it to Washington last week, you can still see the video stream of the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony for the Filipino Veterans of WW II.

Your tax dollars at work.

As I reported in a previously scooplet, Celestino Almeda spoke on behalf of all the veterans and got the biggest applause of the day as he thanked all the fallen soldiers for “sharing this glorious day.”

He ended by saying, “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

The last two words were practically sung with a joyous glee. The crowd responded with nearly 21 seconds of sheer love and adulation.

The other rich moment came with the initial recognition of Almeda, and the realization that this 100-year-old vet had outlived it all: World War II; the post-war politics of the Rescission Act of 1946 that took away promised benefits to the Filipino Scouts and guerrillas who served with US forces; and every last one of his Congressional detractors–and there were many–who time and again denied Almeda and his fellow vets their just due.

What this ceremony called for was a serious apology. Sen. Charles Schumer of New York was able to summon up a little something for the veterans.

“After far too long a delay, we honor them today,” Schumer said. “It’s a mark of a confident and exceptional nation to look back on its history and say that we made a grievous error, but we recognize it, and pledge to never let it happen again.”

Was there a “Sorry” in there somewhere?

And while we’re at it, maybe Donald Trump should say that pledge.

It was painful to watch the ceremony, and not just because it was more than a half-hour before any Filipino American spoke.

It was painful to see Congress honor the vets after making life hellish for them for the better part of 70 years.

And then Almeda got up to speak and helped make the ceremony bearable again.

I’ve talked to Almeda a number of times over the years and know he feels badly that he never saw combat.

“I did not even pinch the ear of a Japanese solider,” he told me with a bit of regret when I saw him in his home last summer and asked about what he did during the war.

He told me he spent most of his time in the service unloading ships with food, supplies, and tanks for the front lines.

But he saved his best fight for these golden years.

As other soldiers died on the battlefield or passed on, Almeda was one, who with others led by Eric Lachica of the American Coalition of Filipino Veterans and the son of a veteran, were on the front lines in the equity pay battle.

I remember the protests at the White House and Lafayette Park, and the headline moments, like the chaining of veteran Guillermo Rumingan, who has since passed away.

In recent years, Almeda still had his appeal pending. He would doggedly hound officials at every opportunity, going to public meetings attended by the Obama administration’s VA Secretary Robert McDonald. At one session, the gatecrashing Almeda’s mic was cut off and he was ushered off and silenced.

As I watched the video of Wednesday’s ceremony, I couldn’t help think of that moment and all the moments of protest Almeda went through in just the last few years.

He never gave up the fight for all the vets.

The hounding of McDonald was important because the VA wasn’t aware of its own rules that actually gave the secretary discretion as to what documents would qualify a vet for equity compensation.

So when current VA Secretary David Shulkin took the mic to say that Almeda’s appeal was resolved and he would get the $15,000 lump sum due him, if it was intended to be the “feel good” capper of the day, it didn’t work.

It only highlighted the absurdity of it all.

Keep in mind that in 2009, President Obama finally signed into law the money to provide equity pay to the Filipinos who were in the Philippines and answered the call of President Roosevelt to serve. $15,000 is a pittance. But Almeda had to fight 8 full years in appeals.

Only a medal ceremony got him through. That and being 100. Every day Almeda went without compensation is an embarrassment to the U.S. government.

Dawn Mabalon, who was at the ceremony, chimed in on my FB page. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s not over until we get the history straight so that all Americans understand who we are and what we have done in the making and shaping of today’s America,” she wrote.

Mabalon, fittingly, is an American history professor at San Francisco State. She’s also a friend. But I was closer to her father, Ernesto T. Mabalon, who died in 2005 at age 80.

Ernie Mabalon was one of the unique warriors among Fil Vets of WWII. He was a guerrilla fighter at age 18 who went underground for the United States Armed Forces in the Far East when Gen. MacArthur retreated and uttered, “I shall return.”

It was Mabalon and the guerrillas who kept the U.S. informed with intel during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. In part with that help, MacArthur returned to Leyte, which led to victory in the Pacific.

But Mabalon wasn’t just a USAFFE member; he was also attached to the U.S Army’s E Company, 2nd Battalion of the 66th Regimental Combat team.

He ended his career a sergeant with three ribbons, and a total of six Bronze stars.

Make no mistake, the men and women honored Wednesday were no slouches.

But Dawn Mabalon knows her dad didn’t do any of it for a medal.

“He would have said this,” Dawn Mabalon wrote on my page. “”I wasn’t a mercenary, a soldier for hire. I fought for my homeland. I deserve the benefits afforded to all who sacrificed.'”

Ernie was one tough guy. And once his fight was done, thank goodness, soldiers like Almeda never gave up.

Filipinos who still aren’t sure if their family member qualifies for a replica medal should go to www.filvetrep.org for more information.

The Filipino WWII vets now join a long list of fighters who faced discrimination even in valor. The list includes the Tuskeegee Airmen, the 442nd of Nisei veterans, the Navajo Code Talkers, and the all-Hispanic 65th Infantry Regiment of the Korean War, all of which have been honored with the Congressional Gold Medal. Only the Filipino vets had to fight to restore the legitimacy of their service.

But how’s this for irony of ironies. The Filipino vets got their medal and stand among fellow honorees like Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who led most of the vets to victory. And then there was awardee President Harry S. Truman, who signed the Rescission Act of 1946 taking away benefits from the Filipino vets.

As I said, I wasn’t at the ceremony. My father missed out on the war. And in that sense, he missed out on the best route Filipinos had to the American middle class.

The path went from American colonial who couldn’t own property, to a spot in the military, to GI Bill recipient. Service to America was the affirmative action where you put your body on the line. And it was the difference for many families.

So it was great to see friends and family post their pictures on the web to capture the joy of their veteran getting the heralded Congressional Gold Medal.

My Uncle Mel was represented by his son-in-law, Lt. General Ed Soriano. It was a great honor for my cousins and the entire Guillermo family.

But it’s just one night after 70 years.

Like old soldiers, the night’s memory will fade away.

It won’t take away the pain of denial and the scars of a bitter fight waged against Congress, which was happy to play the attrition game–counting on veterans dying–before being forced to take action.

Congress deserves no medal for that. Not even its own.

But let’s hope the good memory last at least a few more weeks. Will the country even remember the vets got a medal when it celebrates Veterans day, Nov. 11?

Emil Guillermo is a veteran journalist and commentator. He performs stories from his column in his one-man show “Amok Monologues.” See it live in Baltimore Nov.4,5, 11,12.

Tickets: https://charmcityfringe.ticketleap.com/amok-monologues/

Contact: emil@amok.com