The Ke-Ehi Lagoon Memorial was built in the 1960s to honor fallen soldiers, particularly the men from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

The Ke-ehi Lagoon Memorial is not a very popular tourist attraction in Hawaii. I had never heard of it until three weeks ago. It’s a fairly small, quiet park located on 11 acres near Honolulu.

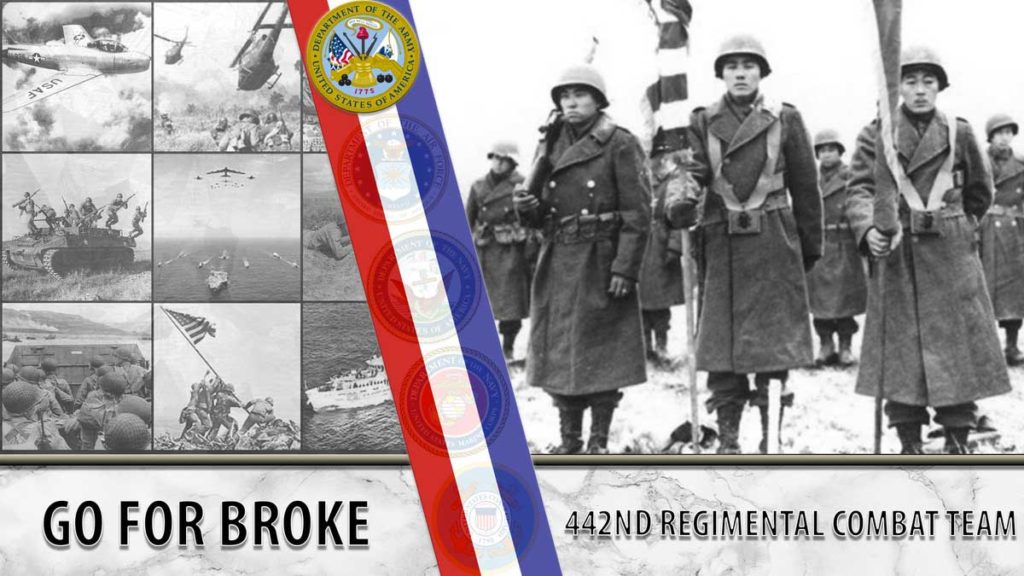

It was built in the 1960s to honor fallen soldiers, particularly the men from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd was the most decorated combat unit in World War II known for their battle cry “Go for Broke!” and was composed entirely of Japanese Americans.

My son was commissioned as an officer here two weeks ago. The event would typically be held at an auditorium on the University of Hawaii campus. But the pandemic forced the change which actually made the event more meaningful.

I had never heard of the 442nd until I moved to the U.S. 30 years ago. And I came to know about them through another painful chapter in American history.

Here’s something many people don’t know: some of the bravest men to fight fascism during World War II were doing so while their families were suffering in what were essentially concentration camps back in the United States. Their offense: being of Japanese descent.

The families of the men of the 442nd had been forced to abandon their homes and their small businesses and forcibly relocated in internment camps throughout the western United States.

I also had not heard of the Japanese internment until I moved to the U.S. in 1990 and worked as a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle.

It was during that time that I became exposed to an aspect of the Second World War that I previously was totally ignorant about. Of course, I knew about World War II — but through the eyes of Filipinos, particularly my father.

It was, for him and our family, a painful memory.

My father was in his teens when Japan invaded the Philippines, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. A native of Naga, he had moved to Manila for college. Suddenly, everything changed.

Like thousands of young Filipino men, he was forced to quit school and join the guerrilla underground. He was arrested and interrogated by the kempetai, the Japanese secret police. They later also picked up his brother, my Uncle Jesus, who was never seen again. Our family presumed he had been executed.

As the war was ending, my father joined other guerrillas in the armed resistance in the mountains in his native province of Camarines Sur. He had been an athlete as a young man. Years in the jungle took its toll on his health.

But my father knew it had to be done. He had to fight. Like the men of the 442nd, his country was under siege. He had to “go for broke.”

What was surprising was that despite the horrors that he endured, my father did not bear much ill will toward the Japanese.

I remember how he would remember the war with barely a hint of anger and would use fairly precise language. “The Japanese soldiers back then were very brutal,” he would casually say. Or, “The Japanese imperial forces really caused a lot of damage.”

The empire, not the Japanese people, were to blame for the suffering and destruction. He even grew to admire Japan’s economic rise. I never hesitated to introduce him to my Japanese American friends.

One regret I have is I never got to talk to him about how I came to know more about the Japanese American experience during World War II — and how it gave me a different view of the war that devastated his community, his family and his health.

In June 1994, I covered Emperor Akihito‘s visit to San Francisco, where, in an extraordinary gesture in Japantown, he apologized to a group of former internees for the suffering they endured during the war.

By then, the United States under President Reagan had apologized for the camps, which led to the payment of reparations to the survivors of that dark chapter in American history.

A few weeks after the Japanese emperor’s visit, I joined former internees on a pilgrimage to Tule Lake, one of the largest Japanese American internment camps.

Barbara Muramoto was just 9 when she and her family were sent to the camps. I was sitting near her on the bus. As we entered the desolate field of sagebrush and dirt that once was her home and prison, Muramoto choked back tears.

Other Japanese Americans responded to the internment by trying to prove their captors wrong. That’s what made the 442nd’s bravery extraordinary.

It was only in the 1970s that young Japanese American community activists focused on the internment and led the campaign for an official apology and reparations. But the humiliation that the Japanese Americans suffered was so intense that many of them refused to talk about their experiences for decades.

Another Tule Lake pilgrim, Joan Miura, spoke of her father’s painful silence. She underscored the lesson of the Japanese American internment: A community forced to endure any form of collective humiliation — whether in the form of war, invasion, slavery, the Holocaust or colonial rule — bears scars that takes decades, even generations, to heal completely.

“I sort of figured out that it had to do with the shame,” she said, “the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the shame of his government’s racism, the putrefied shame of your loyalty being questioned.”

When I wrote an essay about my father’s war experience and the Japanese American internment, I received a short letter from a survivor of the camps. He was about my father’s age. He said something like, “I would have wanted to get to know your father, and I’m sure we would have been friends.”

More than 20 years later, about a decade after my father passed, his grandson took his oath as an officer at a memorial in Hawaii for soldiers who in the face of tyranny knew they had no option but to “go for broke.”