Starting in postwar Manila, homesick G.I.s mutinied in 1946 and won

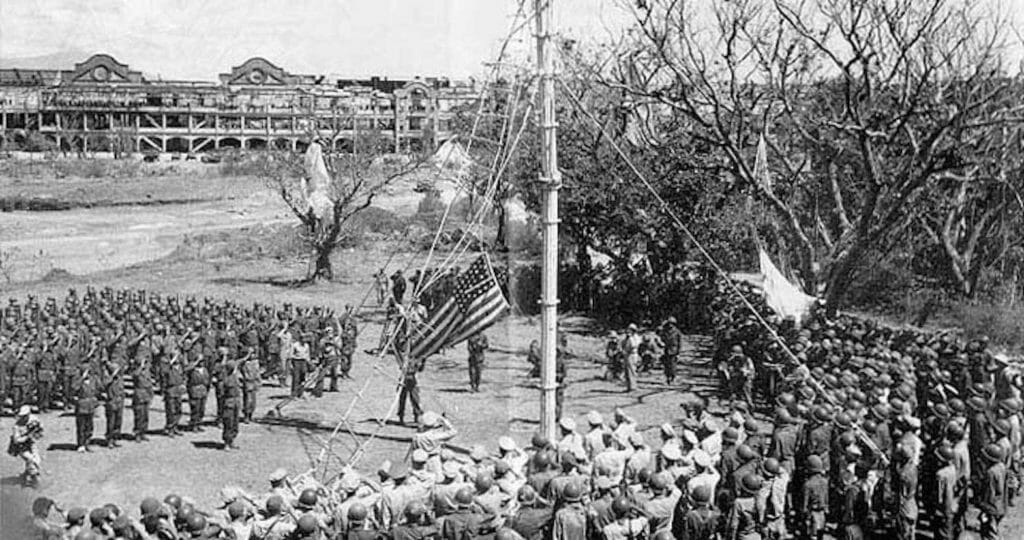

American G.I.s at flag-raising in recaptured Corregidor. Thousands of them mutinied in 1946, demanding repatriation.

In a little-known episode of WWII, thousands of U.S. soldiers deployed in the Pacific and Asia mutinied in 1946, demanding they be sent back home as the Axis powers had surrendered. The G.I.s defied their superiors and President Harry Truman, and won.

Being in their thousands, they could not be punished by death or other court-martial penalties. That mutiny began in Manila.

Shortly after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Washington decided to keep some 2.5 million troops overseas in fear of nationalist independence movement in parts of Asia.

“That did not go over well with the soldiers’ families, who bombarded their congressional representatives with photos of children missing their fathers and pairs of baby shoes with tags reading ‘Bring Daddy home’,” reports The Washington Post, which revisited the episode in time for last week’s Veterans’ Day commemorations.

Feeling the growing home-front pressure, the U.S. government began repatriating G.I.s. But a panicked President Harry S. Truman in January 1946 ordered a slowdown in demobilization, angering the homesick soldiers.

“The first demonstrations took place in the Philippines, then a U.S. colony, which U.S. forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur had retaken from the Japanese by February 1946. More than 20,000 American G.I.s marched in Manila, demanding to be sent back home,” recalls The Washington Post.

“Another 20,000 demonstrated in Honolulu … 3,000 joined them in Korea, and 5,000 in Kolkata. In Guam, 3,500 Air Force troops staged a hunger strike, while 18,000 soldiers pooled money to send a cable to journalists making their case for repatriation.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman privately denounced the mutineers but relented and approved demobilization.

“The armed forces were segregated at the time, and all 250 members of the all-Black 823rd Engineer Aviation Battalion in Burma sent a letter to Truman, saying they were ‘disgusted with undemocratic American foreign policy’ and did not want to ‘take the field in league with the alien rulers against the freedom revolts of the oppressed peoples’.”

G.I.s openly denounced high-ranking officials who tried to reestablish discipline. President Truman privately said it was “plain mutiny” by “babied and spoiled” soldiers.

But just a day after the biggest protests erupted in Manila, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower said the military would not discipline the protesting soldiers because there “had been no acts of violence or disorder.”

Truman’s approval rating was going down at the time, and he didn’t dare reprimand or punish the young soldiers who were overwhelmingly seen as heroes of “the good war.” Within a year and a half, Washington had demobilized to fewer than a million men.

Aside from political pressure the mutineers could apply on Washington, they also benefitted from the legacy of social movements on the home front.

“Some of the protest leaders in Manila and elsewhere had been prominent labor activists at home, and they knew how to use their negotiating leverage to get what they wanted. Meanwhile, the March on Washington Movement had been pushing for an end to military segregation, and Black regiments overseas took up similar protests,” reports The Washington Post.