I have crossed the Golden Gate Bridge more than 100 times in the 46 years that I have lived in this “City by the Bay,” but my most memorable crossing occurred 45 years ago this week. I was riding in a 4-car convoy that left the International Hotel (the “I-Hotel”) in San Francisco’s Manilatown at about 5 p.m. headed for a weekend retreat at Camp Arequipa, a girl scout camp in Fairfax, Marin County.

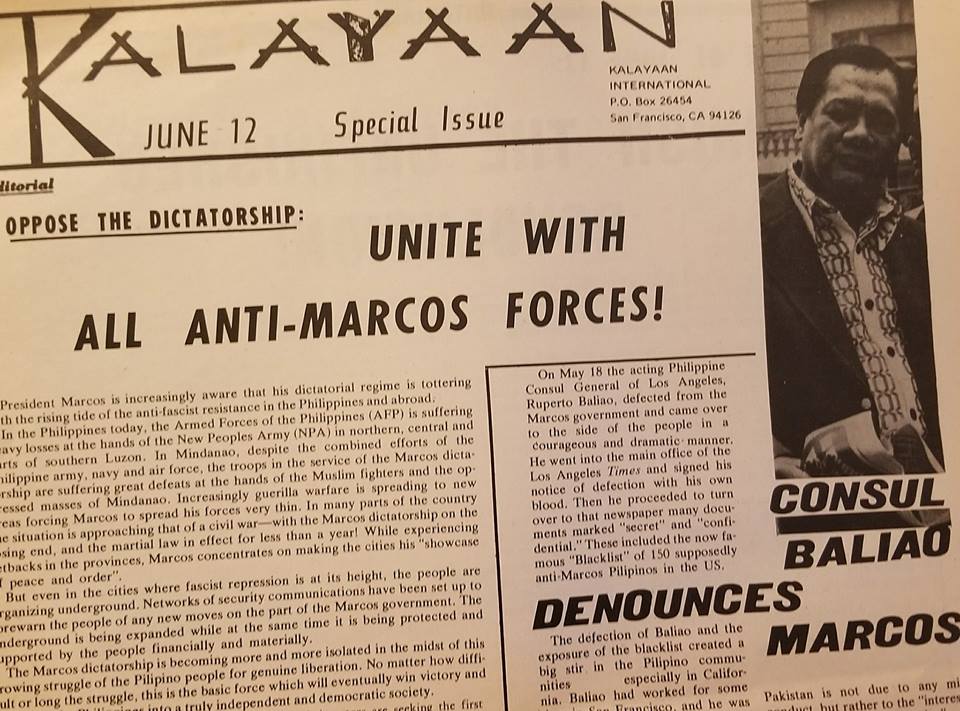

There were about 20 of us, young Filipino activists from all over the U.S. who were coming together to discuss the effective national distribution of Kalayaan International, our radical monthly community newspaper which I started in my tiny room at the I-Hotel in May of 1971.

One of the members of our Kalayaan Collective, Cynthia Maglaya, a veteran of the First Quarter Storm (FQS) of activism in the Philippines, suggested the conference to invite our correspondents throughout the US to come together to create a more systematic network of distribution and, also, to “consolidate the progressive forces”, as Cynthia said. We all heartily agreed and plans began for a conference initially set for April, 1972 but which was postponed to June 1972 and moved finally to September 1972.

While our radical paper drew support from FQS activists who had immigrated to the US, it also attracted Filipino Americans who had never even visited the Philippines and could not speak Tagalog or Ilocano but who were finding their identity consciousness as Filipinos within the broader Third World and Asian American movements sweeping the country.

Meeting at a Girl Scout camp

Among those flying in, or driving up, to San Francisco for the Kalayaan conference were: Eddie Escultura from Chicago, Greg Santillan from Philadelphia, Jaime Geaga and Esther Soriano from Los Angeles, Paul Bagnas and Felix Tuyay from San Diego, Terry Bautista and Sylvia Savellano from Oakland, John Foz and Joe Tolero from Daly City, John Silva, Tessie Zaragoza and Bruce Occena from Berkeley, Cathi Tactaquin from Salinas, Emil de Guzman, Bill Sorro, Gil Mangaoang, Estella Habal and Gil Carillo from San Francisco.

I vividly recall crossing the Golden Gate Bridge and observing the glorious orange sunset when suddenly the news blared over the radio that Ferdinand Marcos had just declared martial law. We were shocked but not entirely surprised by the news as we had been predicting it in our newspaper for months. Sadly, we imagined the thousands of Filipinos in the Philippines who would be arrested, tortured or killed resisting martial law. We imagined the closure of democratic institutions like the courts, the press and the Congress.

When we arrived at the girl scout camp, we quietly gathered together at the main cabin and readily agreed to scrap all our painstaking plans for the growth of Kalayaan-International as the events in the Philippines had overtaken us. We would now have to focus on how we were going to respond to the challenge of martial law.

We decided to form a national organization and establish chapters all over the US. At my suggestion, we called our group the National Committee for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in the Philippines (NCRCLP). When Sen. Raul Manglapus later formed his own national group in Washington DC in 1973, he had the right idea. Movement for a Free Philippines (MFP), short and sweet.

Mapping strategic plans

Round the clock, without taking any time off to tour the majestic canyon views of Camp Arequipa, we laid out plans to organize a National Day of Protest on October 6 to show the world that Filipinos in America were opposed to the Marcos dictatorship.

If we had not planned our conference when we did, coincidentally on the weekend martial law was declared, it would have taken us months to plan and organize a national conference to deal with martial law. It was serendipity.

In our discussions, we analyzed that Marcos would not have declared martial law without the consent and approval of the United States so we believed that key to ending martial law was to lobby the US Congress to cut off military and economic aid to the Marcos Dictatorship.

In his book, ”Waltzing With a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy,” New York Times correspondent Raymond Bonner published CIA memoranda showing that the Marcoses donated $250,000 to Nixon’s 1972 presidential campaign and that before he declared martial law, Marcos called up Nixon to give him a heads up about martial law and Nixon assured him that he had no problems with Marcos becoming the absolute dictator of his country.

We created an NCRCLP Research Committee which met regularly in the basement of the Berkeley home of Lydia Araneta and Nilo Sarmiento, with Craig Scharlin and Lilia Villanueva, Mike and Elena Swanson, and Lydia’s “kids,” Christine and Anna Tess. We would later establish contact with Dr. Ellen Snow, the foreign policy adviser of California Sen. Alan Cranston, regularly providing her with information about martial law.

Sen. Cranston denounces Marcos in the US Senate

The information we provided Dr. Snow inspired Sen. Cranston to deliver a speech on the floor of the US Senate on April 12, 1973, where he said “Foreign dictators seem to feel that all they have to do is proclaim their anti-communism and we will rush to their side with dollars and guns. A few of them, such as President Marcos, even pretend that they are strengthening democracy.”

Two young activists who were arrested in the Philippines during martial law were deported to the US because they were US citizens. When they arrived in San Francisco, we met with Melinda Paras and Deanie Bocobo and arranged for them to go on a speaking tour throughout the US and to speak about their personal experiences in the Marcos prisons.

Another American who was deported from the Philippines was Fr. Bruno Hicks, a Franciscan priest who spent 10 years in Negros organizing farmers cooperatives, before he was arrested by Marcos soldiers, imprisoned and deported back to San Francisco. In the speaking tour we arranged for him, Fr. Hicks described “simple and conscientious peasants forming their own political opinions, expressing them, beginning to vote independently of their landlords and their employers. Could this have been the reason martial law was declared because democracy was actually beginning to work, because the grievances of the masses were finally getting organized, getting aired, and bringing pressure to bear on the political institutions?”

The NCRCLP Cultural Group was formed where the young members sang patriotic Filipino songs like “Ang Bayan Ko” and performed skits depicting the effects of martial law in the Philippines and exposing the US role in the declaration of martial law. The Glide Memorial Methodist Church under Rev. Cecil Williams regularly allowed us to use the church for our forums and cultural performances.

Consul Baliao defects

In October of 1972, the Philippine Consul-General in Los Angeles, Ruperto Baliao, privately informed NCRCLP members of his reservations about martial law. He joked that he may be joining us soon. On May 18, 1973, Consul Baliao held a press conference in L.A. to announce his defection from Marcos whom he called “the new Hitler.” In his cable to Secretary of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Romulo, Consul Baliao informed him: “After many sleepless nights of soul-searching, I have finally decided that I cannot in good conscience continue serving your administration which is dedicated to the perpetuation of Pres. Marcos despotic rule and the continued suppression of our people’s civil liberties.”

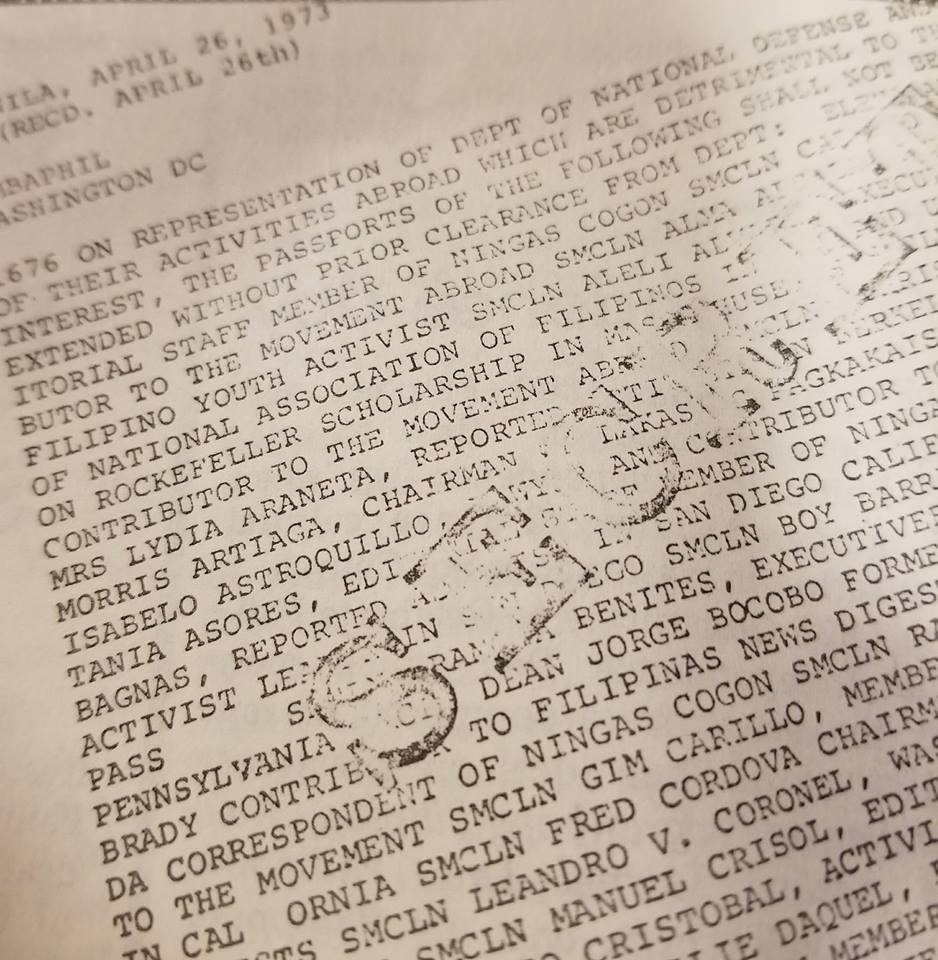

At the press conference, Consul Baliao also presented the official letter from Secretary Romulo confirming his promotion as the next Philippine Ambassador to Pakistan, which was proof that he was not defecting out of fear of being demoted or fired. But he rejected the promotion, he said, because he could not in good conscience continue to represent Marcos. He also revealed a telegram dated April 25, 1973 which he received from the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP) containing a list of over 100 Filipinos in the United States whose activities were considered “detrimental to the national interest.” He was given instructions not to renew or extend the Philippine passports of those in the “Blacklist.”

Philippine government’s blacklist of Filipinos in the US who were suspected of being anti-Marcos elements.

Consul Baliao accepted our offer to go on a nationwide speaking tour sponsored by the NCRCLP. In Washington DC on June 9, 1973, Baliao even led a demonstration in front of the Philippine Embassy joined by Raoul Beloso, the former chairman of the Small Farmers Commission of the Philippines.

Picketing Marcos everywhere

Wherever Imelda Marcos traveled in the US, she was met with NCRCLP pickets. On one occasion, when we learned that she was passing through San Francisco, we rushed to the San Francisco International Airport to picket her. But when we got there, airport police stopped us from setting up our picket line. So I went to the white courtesy telephone and requested the airport announcer to please page a certain individual. As Imelda Marcos was walking through the airport, the loudspeaker blared several iterations of this announcement “Calling Miss Ibagsak C. Marcos, please come to the white courtesy telephone.”

In April of 1973, the Methodist Church offered us free offices at the UNITAS House in Berkeley. Next door to our office was the group fighting the Brazilian Dictatorship. When I dropped by their office and asked them how long they had been organizing in the US against the Brazilian generals, a member responded “since 1964.” That was 9 years at the time and I told him that the Marcos Dictatorship would not last that long. “The Filipino people love and embrace democracy so we will topple Marcos very soon and civil liberties will be restored in the Philippines,” I said confidently.

Raul Beloso, left, former chairman of the Small Farmers Commission and ex-Consul Ruperto Baliao, who defected from the Marcos martial law regime, at the head of an NCRLCP protest march.

How wrong I was. Martial law in the Philippines would last for nearly 14 years from 1972 through 1986.

But NCRCLP would not last anywhere nearly as long. After we published our 36-page newsmagazine, Silayan, in July of 1973, the NCRCLP, as a national organization, would cease to exist.

Cadre over mass

Melinda Paras, who had gone on a speaking tour all over the US after she was deported from the Philippines, forged a political alliance with Bruce Occena of our Kalayaan Collective and together they initiated intense discussions among our NCRCLP members about the need to create a “cadre” organization to surpass a “mass” organization like the NCRCLP.

The result of their efforts was the formal organization of the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP) – which was formed in Berkeley, California in July of 1973. Elected as the national chair was Melinda Paras who insisted, despite my pleas, that NCRCLP must be dissolved in order for the KDP to thrive.

One by one, the NCRCLP chapters around the US was dissolved, all except the Los Angeles chapter under Esther Soriano and Lilian Tamoria, including Eric Lachica. That last NCRCLP chapter, which would later be led by UCLA Prof. Enrique De La Cruz and Atty. Prosy Abarquez De La Cruz, would resolutely continue the NCRCLP until the end of martial law in February of 1986.

So ended what began with the convoy crossing of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1972.

(The author taught Philippine History at San Francisco State University when martial law was declared and would later serve as Secretary-General of the NCRCLP. Send comments to Rodel50@aol.com or mail them to the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127 or call 415.334.7800).