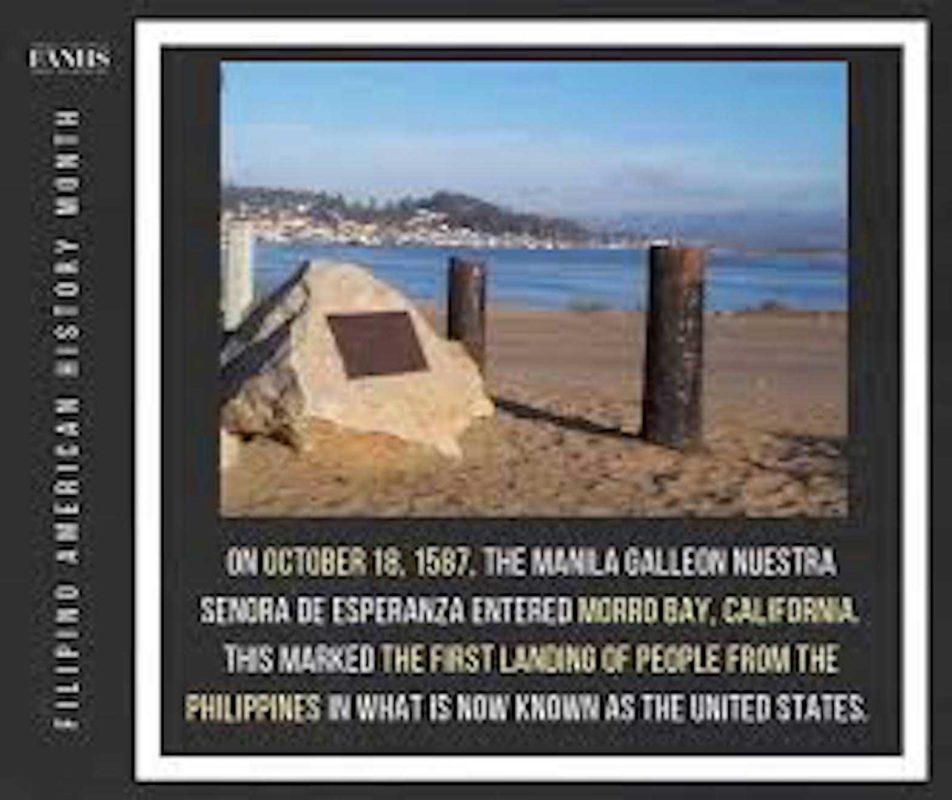

The Filipino National Historical Society marker in Morro Bay, California, marking the presumed site of the first landing of Filipinos in the New World. FANHS

Here’s the problem. Our origin story is good. But it’s not perfect. When did the first Filipinos set foot in the New World? Hint: It was way before a syncopated Bruno Mars.

But more on that in a second. October is now all our own. From October 15 through Halloween, it’s Filipino American History Month.

We had to share briefly. The period from Sept. 15 and through October has been celebrated as National Hispanic Heritage Month, which double dips into two months and broadens its 30 days not unlike Imperial Spain. It does, however, honor the days that countries conquered by Spain in Latin America and Mexico celebrate their independence. And maybe the month implies the centuries of rule in the Philippines as well. Thanks to Ronald Reagan in 1988, it’s all there as Public Law 100-402.

By contrast, the scope of the Filipino American History Month solely honors the actions of actual Filipinos in America, making it genuinely American history.

In 1991, the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) began to commemorate October, but it wasn’t until 2009 that the U.S. Congress by virtue of House and Senate resolutions officially recognized October as Filipino American History Month.

And after October 15, we have the month all to our own. That’s because it was on October 18, 1587 that the very first Filipinos–some “Luzones Indios” traveling in a Spanish galleon—came ashore on the central coast of California. In Morro Bay, near San Luis Obispo, a sign heralds the arrival of the first Filipinos to the continental U.S., 433 years ago to date.

That’s the origin story. But it does not come without controversy.

Some buy in, but some also question

This month, I’ve been amazed at how much people have come to accept #FAHM. It is a thing because we have made it a thing. Several people, non-Filipino/non-Asian, have out of the blue greeted me with “Happy Filipino American Heritage Month!”

And yet, I know Filipino American historians like Alex Fabros and Daniel Phil Gonzales, have more than a little trouble with our origin story. This week, in my role as the museum director of the Filipino American National History Museum, I spoke with Gonzales, an Asian American Studies professor of the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University, on the FANHS Museum Virtual popup (you can see on YouTube).

He told me that before he became focused on history, and was acquiring his J.D. and preparing for a legal career. That’s when he was asked by a mainstream scholar in Europe about the Unamuno voyage.

“I’m ashamed to tell this story,” he told me. Gonzales had been sent around 30 pages of photocopied material in 1972, one of which noted a simple question if the Unamuno landing was the first known contact of Filipinos with the New World?

“I simply said yes, so we knew about it in ’72,” Gonzales said. He said he never pursued it because at the time he was pursuing a different academic path and figured someone would run with the information.

But the research of Unamuno’s ship logs didn’t get wider mention until 1996. That’s when UCLA’s Amerasia Journal published an analysis by Eloisa Gomez Borah, a librarian and a one-time trustee of FANHS. She makes the case for a Filipino presence, telling the story of how Unamuno was part of a Spanish expedition led by Francisco Gali in 1584. When Gali died, Unamuno lost command of the two ships he inherited after taking a side trip to Macao. Stranded in Asia, Unamuno was finally able to buy another boat, described by Borah as a “single-deck three-masted vessel” named Nuestra Senora de Buena Esperanza.

But the virtue of starting out in Asia was the prevalence of a working crew, mostly from the Philippines.

Eastward to Califorina

On July 12, 1587, Unamuno headed for points east and was at sea until the end of his voyage on November 22, 1587 in Acapulco, Mexico. But there was a brief three-day land excursion between October 18-20 that turned out to be their foray onto California’s central coast.

Unamuno sailed with the Franciscan Father Martin Ignacio de Loyola, nephew of the founder of the Jesuit order, a few priests, and soldiers. The logs also reveal the presence of at least eight Filipinos identified as “Yndios Luzones,” or Luzon Indians from the northern Philippines island of Luzon.

They were jacks-of-all-trade seamen, seen as the brawny manpower of the ship. In an email exchange, Borah told me that too often they were left off the logs.

“Filipinos present on these early explorations and trade ships were overlooked in captains’ logs,” Borah said. “Even in Captain Unamuno’s log, which I chose because he did mention “Indios Luzones” (it was spelled both with an ‘I’ and a ‘Y’), documenting the presence of Filipino natives was inconsistent, as my count in the article provides the proof.”

Borah counted “Yndios” appearing in the logs 42 times total. In 23 times, it was a reference to the native Californians encountered, but 19 times it described the crew. But they mattered on Sunday, October 18. That’s when Unamuno, after anchoring off the California coast in a place he called Puerto San Lucas, formed a landing party.

It was composed of 12 armed soldiers led by Father Martin Ignacio de Loyola, Cross in hand. But even before the Cross, up ahead of them all were two Filipinos armed with swords and shields.

It was their typical formation. But note: The Filipinos were first. Being fodder comes with some privilege. On day one, the expedition climbed two hills, saw no settlements or people, and took possession of the land for the King of Spain. On the second day, October 19, eight Filipino scouts led a priest and 12 soldiers for further exploration.

It was on the third day, October 20 that the expedition encountered violence. But not before there was an effort from the ship’s barber and some Filipinos to make a peace offering of food and clothing. Maybe the natives needed clothes, a meal and a haircut?

Borah said the trouble occurred when the Indians tried to kidnap the barber at which point a violent exchange ensued. The log noted one soldier was killed, but so was one unnamed Filipino, by a javelin, his blood spilled on American soil. Unamuno didn’t stay long. He left by daybreak on October 21 for Acapulco.

The significance of three days

Borah calls it the unique evidence of a Filipino presence that is too often obscured when historians fail to identify or differentiate among non-Europeans in their crew. When I spoke to her, she was adamant.

“Filipino natives, among the non-white Indios of that era, did not write the logs or the letters to the king or any other contemporary documents,” Borah wrote me in an email exchange. “However, Filipino Indios were 4 out of 5 who worked the Spanish galleons (Schurz, 1939) in crossing the Pacific for 250 years, and they were the advance guard in the land expeditions and provided the information evidenced in Captain Unamuno’s log.”

Filipinos didn’t write the history, but they were undeniably part of the story. They were present. “What needs to be done now is the championing of our history,” she told me.

The challenge

The Filipinos were on the ship. But was the ship at Morro Bay? Gonzales says what’s missing from the logs is any mention of a large Gibraltar-ish rock that is a hall mark of Morro Bay. “That is nowhere described in Unamuno’s logs,” he said on the podcast.

When I talked to Gonzales’ colleague Alex Fabros, he was more critical of the latitude and longitude markings on the log, and questioned if a sextant was improperly used. As a sailor, Fabros duplicated the effort and said it was more likely not Morro Bay, but a place north. But still on the central coast of California. The plaque may not exactly be at the right place, but it doesn’t take away the fact that Filipinos were in the new world in 1587. Unamuno’s document is still proof of that.

It’s said that history is written by the winners. Those in power who want to make a claim to a legacy. I’d simply change that to “history is written by the people who care.” And by care, I mean, we want to make sure we show up. If we were there, let people know about it.

White, mainstream historians may not care when Filipinos first arrived. But Filipinos and other Asian Americans do. It’s our story. And as a new generation of historians emerge, it will be up to them to uncover more layers of the truth. Was it Morro Bay? Was it more like Half Moon Bay up the coast? (Possibly) Was there another ship before Unamuno? (Unlikely). The main point is that our inquiry and curiosity continues 433 years after Unamuno. It’s our controversy because it’s the history we’re writing still. And we want to get it right.

Still, we’re left with these facts. Filipinos stepped on the land first, they even spilled blood, before leaving empty-handed after three October days in California, 1587.

Big deal? Sure, when you consider the overall chronology. Of course, there were Native Americans already here. But among Asians, it was the Filipinos who were first.

Remember that in November when we fuss over the Mayflower and Plymouth Rock. Filipinos were 33 years before them on the west coast in October 1587.

Instead give thanks for Unamuno, the barber and the “Indios Luzones.”

It’s why Filipino American History Month is celebrated every October.

Emil Guillermo is a journalist and commentator. He writes a column for the Inquirer.net’s North American Bureau. He is director of the Filipino American History Museum. See more programs about Filipino American history online at Facebook@FANHSmuseum, and on the FANHS Museum YouTube Channel. Twitter @emilamok Listen for him on your podcast apps.