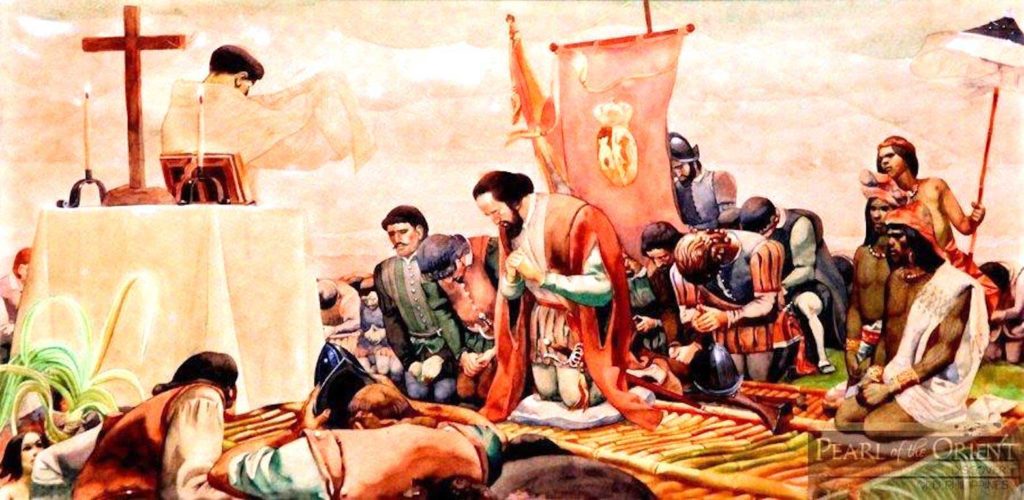

A depiction of the first Catholic Mass in the Philippines.

NEW YORK — On April 27, 1521, almost two weeks after the baptism of Rajah Humabon and his court, came the battle of Mactan, with the resulting death of Magellan in his vainglorious attempt to bend LapuLapu to his will—an outcome that would have redounded to Humabon’s benefit, and to Magellan’s as well, for victory would have validated his boast, his exaggerated sense of his and his men’s superiority in combat. And it would ensure Humabon’s fealty, as well as Magellan’s position as viceroy of the islands, making him and his family fantastically rich and vindicating his defection to the Spanish court.

According to Pigafetta, Humabon had offered Magellan a contingent of his warriors but Magellan turned his nose at the offer, boasting that any one of his men, when clad in body armor, was worth a hundred of the enemy. Besides, he had his cannon—which were far more powerful than the lantakas, the smaller-bore swivel guns of the islanders.

Magellan’s officers pointed out that they had no business interfering in local affairs. Besides, they were fearful of losing all their hard-earned gains. But by now, Magellan had been infected with evangelical zeal, his head full of grandiose notions of lording it over the archipelago. And so he decided to teach LapuLapu a lesson, with only sixty men—all volunteers—and in the process impress his native ally no end.

Unfortunately, Magellan and ships came in at low tide, and were anchored too far from shore for their cannon to be effective. As dawn broke on that fateful day, Magellan and his armed party in three long boats rowed as far as they could, then waded ashore in their body armor to engage LapuLapu and his warriors. (Being April and the height of island summer, the armor-clad men must have been sweating profusely.) Almost all of Magellan’s men were volunteers, except perhaps for Enrique who, I would assume, had no choice but to accompany his master into battle. However, it is entirely possible that, having been in Magellan’s service for a decade, by then Enrique had a sense of loyalty to his master. It seems the latter was a fair man, relative to the times, for in his will, Magellan decreed that upon his death, Enrique would be free and be given a substantial amount of money from his estate.

Of the battle Pigafetta writes, “And thus defending themselves [LapLapu’s men] fired at us so many arrows and lances of bamboo tipped with iron, and pointed stakes hardened by fire, and stones, that we could hardly defend ourselves. … Our large pieces of artillery which were on the ships could not help us, because they were firing at too long range …

Outnumbered and outmaneuvered, the tough, forty-one-year-old Magellan paid for his adventurism with his life, as, wounded in his sword arm and, as Pigafetta records, “a large javelin [was] thrust into his left leg, whereby he fell face downward,” cut down on the beach as his companions, their ranks depleted, fled to the longboats. Pigafetta mourned Magellan’s death, calling him “our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide.”

Enrique does not return to Spain. And we can only conjecture about his fate. Was he killed or did he live to a ripe old age in the islands? Pigafetta’s Relacion has at least three versions, with varying accounts of Enrique’s fate. In addition to arguably being the first man to circumnavigate the world, he was likely the first overseas Filipino worker, foretelling the modern migration of Filipinos abroad to better their lives, and in particular of their prominence as crew members working for the cruise industry, for the moment moribund.

Humabon and LapuLapu can also be viewed as historical exemplars: Humabon for those who collaborate with foreign powers—he has had a multitude of successors—and LapuLapu, for those who insist on sovereignty and thus resist domination. Both anticipate in various ways José Rizal and Andres Bonifacio and the way these two have been regarded in the ongoing debate over reform versus revolution.

Magellan didn’t discover us; we discovered him. His arrival was a Pandora’s Box that not only introduced Christianity to Southeast Asia, but heralded the emergence of the United States as a superpower. One of the poisonous legacies of more than three centuries of Spanish colonialism and half a century of US occupation, and its still dominant influence on pop culture, is, to paraphrase what the great writer James Baldwin once said about race, “The reason people think it’s important to be white is that they think it’s important not to be brown.”

Copyright L.H. FRANCIA 2020