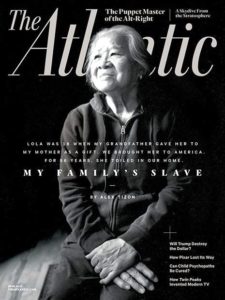

The conversation sparked by “My Family’s Slave” continues.

More stories about the plight of the katulong are coming out. One is Rona Fernandez’s essay “Lucky” which recalls her own mother’s journey as the servant of her aunt and uncle who took her with them when they moved to the United States in the 1960s.

It highlights questions raised in the controversy over “My Family’s Slave.” How many other untold stories of exploitation are out there? How should they be told? Who should tell them?

Rona Fernandez says it is important for others to speak, arguing that “we we have to stop listening primarily to those with the advanced degrees or the Pulitzers, the hefty bank accounts or the grand, dynastic Filipino last names.”

Alex won the Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism in 1997. “My Family’s Slave” unleashed a wave of opinion pieces by scholars and academics.

In fact, one of the odd twists in the controversy over “My Family’s Slave” is that some of the most mean-spirited and arrogantly self-righteous reactions to Alex Tizon’s essay came from people with PhDs who called him a criminal, a liar, a con-man.

Fortunately, there have been many more thoughtful, critically-intelligent, reactions from respected academics who acknowledged “My Family’s Slave” as a compelling, if flawed, narrative that opened a window to a world many Filipinos have been reluctant to discuss.

“What ‘My Family’s Slave’ has done is to bring up a subject that is often left unsaid and left unthought and unexamined a subject that, far from being just a problem of Philippine poverty and corruption and lack of state capacity ‘out there’, implicates all of us who have ever had yayas bring us up and keep house for us,” Caroline Hau, a professor at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University, wrote in a blog post “56 Years A Slave.”

Hau lamented that the conversation about “My Family’s Slave” has involved mainly middle class and upper class Filipinos, shutting out working class Filipinos, including the katulongs, who “are not likely to have the time to browse, let alone post comments in, English-language media.”

“It’s important to ask who is part of this discussion and who is not,” Hau said.

Voice was also a focus of another engaging analysis of “My Family’s Slave” by Vicente Rafael of the University of Washington. He offers the thought-provoking view that even though she was not telling her own story, Eudocia Pulido’s voice at times breaks through in Alex’s narrative.

“She is not entirely silent. Indeed, she speaks throughout the narrative not only through the author’s voice but beyond and around it, even exceeding it.

“Here, then, is part of what is so compelling, at least for me, about this story: that despite the history of her oppressive domestication, Lola remains, in the end, undomesticated. There is always something about her that is held back in reserve, unavailable for exploitation, much less comprehension on the author’s part (and the readers’, too). He probes into her past, for example, and she retreats, her reticence a kind of resistance to his aggressive curiosity.”

Alex certainly would have written an even more compelling essay if he had found letters, notes, tape recordings, any record of how Eudocia Pulido felt and what she thought during her decades of enslavement.

But even that probably would not have been enough for him to tell a complete story. “My Family’s Slave,” while compelling, elegantly-written, would still have come across as Pulido’s story filtered through Alex’s voice.

In fact, that’s one thing the controversy over “My Family’s Slave” has highlighted: the limits of journalism.

Media outlets like Rappler did a good job reporting on the family and friends Pulido left behind in Mayantoc, Tarlac. But reporter Lian Buan’s excellent report was limited in scope and depth, and then was swiftly swept away and forgotten in the next news cycle.

We need other forms of storytelling to build on the conversation that “My Family’s Slave” started. An oral history project, featuring extended, unedited interviews with Filipinos who worked as maids and their families could give us a more complete, in-depth, nuanced picture of the world of the katulong.

One powerful medium already has a strong foundation in the Philippines, enabling historically silenced communities to have their voices and stories heard: people’s theater.

A pioneer of this medium, the Philippine Educational Theater Association, better known as PETA, is marking its 50th anniversary this year. For five decades, PETA and other groups have make it possible for farmers, factory workers, servants to explore their experiences through theater and performance arts.

The performances and workshops are held not in fancy auditoriums or performance halls, but in barrios and urban poor neighborhoods where communities are able to tell their stories their own way.

“Part of the process of mounting a play is exploring the truth,” my friend Nanding Josef, a PETA veteran and now creative director of Tanghalang Pilipino at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, told me.

That’s not easy when you’re trying to encourage people who may not feel that they deserve to be heard to tell their stories.

“Kaya mahalaga na ang mga manggagawa, magsasaka, katulong at iba pa ay mailagay sa isang sitwasyon na maharap nila at maibahagi sa iba nang walang takot kung ano talaga ang nangyari at ang totoong naramdaman at naranasan nila.” (That’s why it’s important to offer workers, peasants, maids and others an opportunity to explore and share without fear their experiences and emotions.)

“The theater process liberates them,” Nanding said.

Journalism, on the other hand, can create blinders. This was an important lesson I learned from my journalism professor at UC Berkeley, the late filmmaker Marlon Riggs.

Marlon’s main advice to my class goes something like this: Always be aware of the voice in the story. In most cases, it’s yours. You control the camera, the microphone, the words, the photos, the details that will go into the story. But usually these won’t be enough to tell the complete and definitive story. Because, in most cases, the people you’re covering as journalists are the most qualified to tell their own stories. But in most cases, they’re not able to.

Marlon spoke from experience. He knew what it was like to be voiceless and invisible — like the katulongs and servants in the Philippines. He was African American in a predominantly white society, and gay in a community in which homosexuals were historically rejected and demeaned.

To survive as a young man, he recalled in his 1991 essay “Notes of Signifying Snap Queen,” Marlon “assumed the impassive face and stiff pose of Silent Black Macho.”

“I wore the mask. I was serving time; for what crime I didn’t know. But I wore the mask, however stiff, confining, suffocating.”

Marlon, who died in 1994, eventually broke free. He took off the mask by exploring his own story and voice as he did in the brilliant, autobiographical documentary “Tongues Untied.”

“I unchained my tongue. I spoke. I learned yet again the inestimable virtue of my own distinctive voice, my native tongue. As communities historically oppressed through silence, through the power of voice we continually find our freedom, realize our fullest humanity … We speak, creating a world that speaks, and listens, to us. Thus we affirm our right and our fight.”

I’ll reaffirm here what I said in an earlier column: “My Family’s Slave” was the final act of courage of one of the best journalists of my generation who grappled with an ugly past and then found the strength to explore and expose it.

Alex Tizon left many unanswered questions. But because he had the guts to tell a painful story, a very important conversation has begun.

It’s a conversation that I believe he would have embraced. I can imagine Alex even agreeing: ‘Yes, we need to find ways for the other Lolas of the world to tell their own stories.”

In a way, that’s what he helped accomplished.

Months before his death, Alex sat in front of a blank screen and began wrestling with the opening sentences of the last and most difficult story he would ever write: “Her name was Eudocia Tomas Pulido. We called her Lola. She was 4 foot 11, with mocha-brown skin and almond eyes that I can still see looking into mine—my first memory. … No other word but slave encompassed the life she lived.”

Several months later, more stories about the plight of the katulong are coming out.

Visit and Like the Kuwento page on Facebook.

On Twitter @boyingpimentel