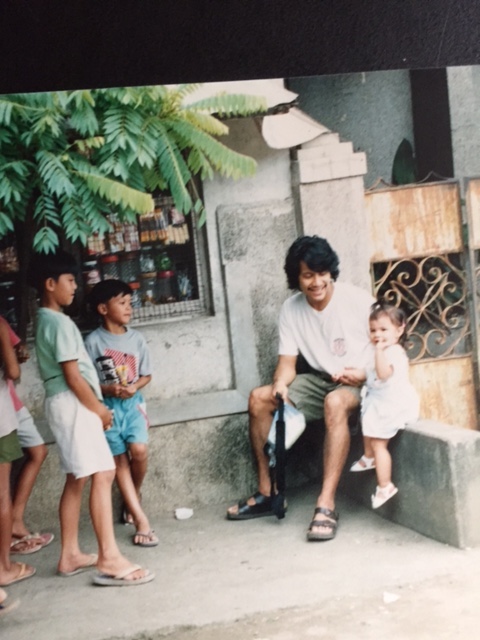

Alex Tizon in the Philippines. CONTRIBUTED

Despite the criticisms, some thoughtful and provocative, others laced with hateful insults, this must be said: “My Family’s Slave” was Alex Tizon’s final act of courage.

His decision to write about Eudocia Pulido’s life as an indentured servant who received no pay for decades while being abused by his parents took guts and incredible personal strength. The seething, spiteful comments prove that.

Alex had taken heat for writing about other controversies. He knew Pulido’s story would trigger a bigger firestorm that was bound to engulf him and his family.

And yet he wrote it.

He could have just kept quiet and let Eudocia Pulido and her tragic story be forgotten. But he did not.

It is wrong to downplay the ugliness of the family secret that Alex exposed. But the consequences of what he did are also worth highlighting in order to draw lessons from what happened to Lola, as Eudocia Pulido was known to Alex and his family — and to find ways to make sure it never happens again.

“My Family’s Slave” exposed Alex and his family to anger and ridicule. But it also sparked a heated, much-needed discussion and debate on how domestic helpers are treated in Filipino culture.

The unexpected twist in Alex’s decision to tell Pulido’s story is that he died before The Atlantic ran the essay.

Alex is not around to answer the questions about Pulido’s life and his complicity in her ordeal. He is not here to respond to the hate, some of it in the form of self-righteous and mean-spirited attacks.

To be sure, “My Family’s Slave” left many unanswered questions, including those now directed at Alex’s siblings: ‘Why didn’t you do anything sooner? Why did you let Lola suffer for so long? Why didn’t you do something about her situation?’

These are valid questions. I found some answers from someone who shared a deep bond with Alex and who lived with the painful secret he exposed: his younger brother Albert.

A protracted, secret struggle

Albert, also known as Al, is a Christian minister now based in Chicago. We first met in 1992 in Manila when he was living there as part of his work. We reconnected on Facebook after Alex died in March.

I sought him out after “My Family’s Slave” was published. By the time I reached him, his family was reeling from the public insults and attacks. Melissa Tizon, Alex’s widow, has been speaking for the family in media interviews. But Albert agreed to share his thoughts.

The conversation we had was brief. He was about to go on an overseas trip. He said the Tizon family supported Alex’s decision to tell Pulido’s story, including his decision to use the term “slave.”

Albert offered an important insight, one that for some reason Alex downplayed in the essay. As Albert tells the story, Alex and his siblings did try to do something about Pulido’s situation, and they did this much sooner than what Alex portrayed in the Atlantic essay.

Alex recalled in “My Family’s Slave” the battles the Tizon siblings — including their oldest brother Art and two younger sisters, Leticia and Maria — had with their parents, especially their mother, over their treatment of Pulido.

Albert lamented that those efforts to change the way their parents treated Pulido came across as inadequate and insignificant to some of their family’s critics “who I guess wanted us to mount a revolt.”

There was no revolt. There was no uprising. But what the Tizon siblings did was wage a protracted, secret struggle to help Eudocia Pulido, to free a woman they came to know as their mother but whom they knew was a victim of abuse.

“As we got older, in our late teens and early twenties each of us was willing to do anything to improve Lola’s situation,” Albert told me. “We offered to buy her a [plane] ticket and arrange her family in Tarlac to receive her back. We would ask Lola, ‘What’s keeping you here? How can we get you out of here?

“Lola’s reaction was always, ‘Where do I go? I can’t leave your mom. I love your mom. I love all of you.”

But they kept trying, Albert said.

They explored with her the option of returning to the Philippines to be free of their parents. Eventually, she seemed open to their plan although she cited milestones that she wanted to reach or witness before making the move. She would return home, she would say, but not until this sibling reached a certain age or another sibling graduated.

“As we got older, we tried to do more,” Albert said. “But the more time that went by, Lola was resolved to stay here. She just had all kinds of reasons.The biggest reason was, ‘I can’t leave your mom. I promised her dad that I’m not going to leave her. Where that kind of loyalty comes from, I have no idea. If it were me, I would have left the first month.”

“What were late teenagers and early 20-year-olds going to do?”

In fact, they were in their 20s in the 1980s when Alex, Albert and the Tizon siblings found a way to at least fix one of Lola’s problems caused by their parents’ neglect: her legal status.

Alex spent a lot of time digging up details of this effort as he was working on “My Family’s Slave.” He shared one of the fruits of his research with Albert in a Facebook Messenger last September.

“Well done!” Alex said in his first message. The following message was a PDF file.

It was a copy of a typewritten letter dated April 29, 1986 that Albert sent to an Oregon law firm. (It was addressed to a Richard L. Hendrie Jr. who is listed as being based in Salem, Oregon. I tried to reach him, but was unsuccessful. His listed phone number and his office web site were no longer active.)

Albert’s letter described Eudocia Pulido’s legal dilemma, which he said was due to their father’s neglect of her status and later, after their parents divorced, to their mother’s inaction because she “was fearful to do anything.” He referred to Pulido as Lola in the letter.

“And now in 1986, 17 years almost to the day that Lola could not be considered legal, the Tizon children, who are now old enough to know what happened, want to overcome this fear that inevitably spilled over on us, and attempt to make Lola a legal person in the U.S.,” Albert’s letter said.

The Tizon siblings, he added, hoped that obtaining a legal status would allow Pulido to “go home to the Philippines and back, and also so that she may enjoy the privileges of citizenship such as employment, owning a driver’s license, social security, etc.”

However, he also noted that they hoped this could be accomplished “without getting our Dad and/or Mom in any kind of legal trouble” for neglecting Pulido’s legal status.

Albert expressed surprise after seeing Alex’s messages: “Wow! Where did you dig that up?”

“Going through boxes of stuff,” Alex responded. “You did good, brother.”

“I don’t think it did anything,” Albert wrote back. “But I think it was an attempt. I don’t really remember the circumstances around that letter. Did we sibs conspire and I was assigned to write this up?”

Alex said: “I was out of the loop on this one, so I don’t how you came to write it. A year and a half later Lola got her green card so maybe your letter did do something. Maybe the lawyer advised you on the process and it started her on the path? Anyway, the letter fills some holes I had trouble filling.”

These details are not in Alex’s essay, which does not try to highlight their earlier attempts to help Eudocia Pulido. “I can only speculate that what he really wanted to draw out was the atrocity,” Albert said.

The disclosure of that atrocity turned a harsh spotlight on their parents. It is one consequence of Alex’s story, Albert said, that the family is still grappling with.

“That’s what makes this story so complicated,” he later told me in an email. “We didn’t really talk about this over the phone. I don’t know if anyone has even tried to understand that the horrible things people are saying about our parents are very hurtful, too.”

The controversial obituary

Also painful for the family was the controversy over Eudocia Pulido’s obituary in the Seattle Times in November 2011.

The obituary by Susan Kelleher titled “Lola Pulido lived a life of devotion to a family” was pitched by Alex who also was the main source for the article.

After “My Family’s Slave” was published, the Seattle Times ran a follow up article by Kelleher titled “Why the Obituary for Eudocia Tomas Pulido didn’t tell the story of her life in slavery.”

It was highly critical of Alex. Albert said it hurt that it ran in a newspaper where “Alex worked tirelessly and faithfully for 17 years.”

“An obituary was not the place to talk about it,” Albert said. “How many angles to a story can you count? Is it a lie if you don’t reveal every angle of a story?”

Another friend of mine, who is also journalist, agreed with the Tizons, arguing that obituaries typically leave out negative aspects of a person’s life.

But on this issue, Albert and I disagreed. He elaborated on his views in an email, which is worth quoting in full:

“There is so much to the story of a person’s life. Neither the obit in the Seattle Times six years ago or Alex’s last article tell the whole story of Lola.

“The question of why Alex didn’t say everything to Susan at the Seattle Times or why he didn’t include this or that in his own article are after-the-fact luxuries that we as readers have. It’s just unfortunate that when some use their luxury, they have to attach judgment to it.

“Alex didn’t lie to the Seattle Times. The sentiments expressed in the obit were accurate and well written. Lola’s story with us was indeed a family love story. It is also a tragic story of class abuse, Filipino history and culture, emotional anguish, redemption largely at the hands of Alex and Melissa, how Lola’s life shaped each of the children, etc.

“If Alex shared with Susan his deepest thoughts on Lola, which were not as developed as say, when he began writing his thoughts down that eventually became the Atlantic article, then the obit would have turned into something else.

“Someday, someone might attempt to write a full biography of Lola, but I’m willing to bet that he/she still won’t capture everything.”

My own view is that Alex’s decision to propose the obit sprang from an early and perhaps flawed attempt to honor Eudocia Pulido. But making that pitch at a time when he was not prepared to reveal the whole truth was a mistake.

Kelleher raised a valid point when she wrote that, in not disclosing everything about Pulido, Alex denied her “the truth of her life, and the rest of us an important piece of our history.”

But then again, maybe Alex eventually realized that himself.

As he recalled in “My Family’s Slave,” Pulido’s death was very sudden: “Before I could grasp what was happening, she was gone … I can still see her on the gurney. I remember looking at the medics standing above this brown woman no bigger than a child and thinking that they had no idea of the life she had lived.”

Did he pitch the obituary to the Seattle Times, which ran 12 days after Lola died, out of an overwhelming desire to make the world know about the life Eudocia Pulido lived?

But did Alex eventually come to the conclusion that that wasn’t enough?

Did he perhaps even realize that that was a mistake, that the one and only published account of Eudocia Pulido’s life should not be an incomplete retelling of her story?

And was that when Alex decided that a more complete story of Eudocia Pulido, her heartbreaking journey as his family’s slave who was also a beloved mother to him and his siblings, had to be told …and that he was going to write it.

A meaningful debate on class and slavery

And because Alex found the courage and strength tell that story, a spirited, meaningful, if sometimes nasty, conversation on slavery and class in Filipino society has begun.

Many are engaging reads like this essay by the novelist Ninotchka Rosca who noted that Alex “did not evade the issue” of what Pulido endured by using the word “slave.”

“The word was a trigger,” she wrote. “It named the essence of a servitude familiar to Filipinos, both at home and overseas.”

There have been others that offer thought-provoking critiques of Alex’s story.

One of them is the graphic essay “The Slavemaster’s Son” by Sukjong Hong who argued that Alex’s essay “still bears the signs of a slave story told from the perspective of a slave master’s son.”

Reading that essay made me remember a paragraph in Alex’s essay where he recalls Pulido’s death: “She’d had none of the self-serving ambition that drives most of us, and her willingness to give up everything for the people around her won her our love and utter loyalty. She’s become a hallowed figure in my extended family.”

I do not doubt for a second the love that Alex and his siblings eventually shared with Eudocia Pulido. But given what she went through, Alex’s observations about her come across as awkward and deficient.

As Hong also noted in the graphic essay, Alex “somehow ignored the ways that the power dynamic between him and Eudocia would tilt the narrative in his favor, and close off parts of her from him.”

This insight applies not just to Alex and the Tizons. It applies to many of us, middle class Filipinos who grew up in a culture where having a katulong, a maid, who would faithfully serve and take care of our family’s needs was a normal facet of life.

In most cases, these servants forever remained nameless and faceless for us as Rosca noted in her essay: “I can see a procession of women whose last names I never knew but who served my family.”

“Benign feudalism,” my friend Jane Po, with whom I’ve been discussing Alex’s essay, called it. “They have been conditioned by society to think they are inferior.”

I can imagine Alex engaging in and even welcoming such discussions, including those based on criticisms of “My Family’s Slave.”

I can imagine him even accepting his own limitations in telling Eudocia Pulido’s story.

I can imagine him acknowledging that despite his incredible skills as a storyteller, his role in Pulido’s life as the son of the couple who mistreated her for decades, inevitably hampers his ability to tell a complete story.

I can imagine Alex readily accepting that the story he wrote was incomplete, even flawed.

I can imagine him witnessing the intense discussions his story sparked and willingly finding ways to take part in those conversations.

“My Family’s Slave” is not and should not be the final word on the life of Eudocia Pulido and the other Lolas of the world.

But it has turned out to be an important first step in what hopefully will be a meaningful and sustained dialogue and debate on class, slavery and the treatment of domestic helpers in the Philippines and beyond.

“Alex was paralyzed by the horror of having inherited his parents’ secret,” Jane Po told me. But eventually, she added, “he called a spade a spade.”

“That he was unable to break the cycle just shows how deep the issue runs. Kaya ang laking nagawa ng article ni Alex. That’s why what Alex’s article accomplished is a big deal.”

One of the best journalists of my generation

I began writing this partly in reaction to the hateful attacks on Alex and his family. The magnitude of the nastiness hit me one morning when I got a Facebook message from Manila. It included the hashtag #Justventing.

It was from my friend Glenda Gloria, managing editor of Rappler who got to know Alex during his brief journalism stint in Manila, and who conveyed her distress over the sometimes mean-spirited attacks against Alex.

“Boying! Na highblood ako sa haywire comments on Tizon!” she said. “They don’t know him. Alex is the sum of all his work. And his work and life would be the perfect counter argument to all this, his best response now that he is unable to address the issues hurled against him.”

I agree. In fact, Alex Tizon was one of the best journalists of our generation.

[Note: Glenda and the Rappler team have done a excellent job covering the reactions to Alex’s story, including a story on Eudocia Pulido’s family in Tarlac and intelligently provocative opinion pieces such as Shakira Sison’s We Are All Tizons.]

I first met Alex in 1991 when I worked as a summer intern at the Seattle Times. He was already then a much-admired reporter and writer. He approached me at my desk one day to introduce himself and to offer his support.

We became friends especially as we discovered many things in common. One was that we were both from Cubao. His family lived there before moving to the U.S. Alex even shared with me his Filipino nickname: Lecloc.

The following year, after I returned to the Philippines to work on a documentary on the U.S. bases, I was pleasantly surprised to run into Alex in Ali Mall. Lecloc of Cubao was back.

He had taken a leave of absence to spend a year in the Philippines where his brother Al was based as a minister. It was a soul-searching trip, a time when Alex hoped to explore his Filipino self, Albert said.

One conversation from that period still stands out for me. I was working on my documentary with the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. I asked Alex if he would be interested in meeting with the PCIJ editors and staff to share his insights into journalism. He said something like, “I’m not sure I’d be qualified to talk about investigative journalism.”

I remembered what he said six years later in 1997 when Alex reached a high point in his journalism career: winning the Pulitzer for investigative journalism.

He was one of three Seattle Times reporters, including Eric Nalder and Deborah Nelson, who were honored by for exposing the abuses in the federal housing program for Native Americans.

How Alex got involved in the project underscores his strengths as a journalist. The reporting on the story began with a tip followed by an intensive document search, including Freedom of Information Act requests.

As the Times’ account of how the reporters broke the story explains, Alex played a critical role as the project’s lead writer and as a reporter known for his extraordinary ability to get people to talk about their lives.

“As the investigative pair continued their work, Tizon was added to the team,” the Seattle Times said. “Regarded as one of the paper’s most skillful writers, he was beginning a beat called American subcultures, with emphasis on Native Americans. Tizon’s first mission was to visit reservations where abuse had been found by Nelson or Nalder, and document the impoverishment.”

Alex did eventually become involved with the PCIJ as part of a visiting fellowship program sponsored by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) in the late 2000s.

As journalist Ed Lingao recalled in a tribute after Alex’s death, “While he liked to say that he was here in the land of his birth in order to learn, in the end he gave away much more than he took.”

Alex became known as a mentor, as “the philosopher-journalist who could write about the extraordinariness of ordinary people,” Lingao said.

He was still in the Philippines when the Ampatuan massacre happened in 2009. He wanted badly to join the PCIJ team in covering the aftermath of the killing of 58 people, including more than 30 journalists, by a local warlord. But the ICFJ banned him from traveling to Mindanao for security reasons, Lingao said. He was then forced to return to the U.S. “his journalism fellowship cut short by his desire to do journalism,” Lingao wrote.

Ed’s tribute closed with a quote from Alex who offered this advice to young journalists: “Read, read, read. Think, think, think. Write, write, write. Go into the dark places and write about them.”

I last saw Alex in October 2015 at a journalism conference at Stanford University. He gave a talk titled “Self and Story,” based on Alex’s view that “the most honest way to tell a story is through the first-person point of view, and the most compelling story you can tell is your own.”

Only later did it become clear that Alex was already then hard at work on the toughest assignment of his journalism career, probing, confronting dark places in his past, immersed in what turned out to be the last and the most painfully personal and most powerfully important story of his life.

Visit and Like the Kuwento page on Facebook.

On Twitter @boyingpimentel