Toronto: PH Martial Law survivors recall the years of living dangerously

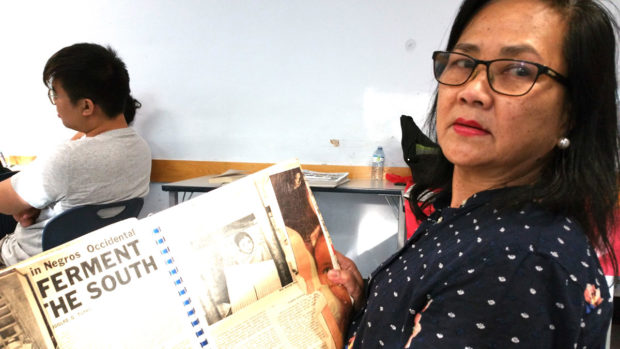

Journalist Mila Astorga-Garcia was incarcerated twice in the Philippines under the rule of Ferdinand Marcos. INQUIRER/Patty Rivera

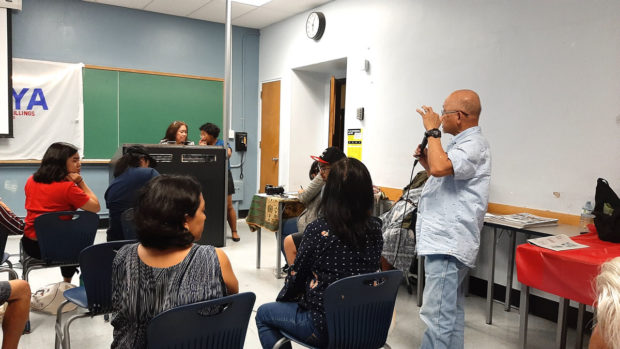

TORONTO — Forty-seven years after martial law was declared in the Philippines on Sept. 21, 1972, survivors of the Marcos years looked back with dread and peered into the future with foreboding, during a forum in Toronto on Sept.22.

In a small room in Kerr Hall at Ryerson University, young university students and their elders gathered to review almost half a century of fraught Philippine history.

How did martial law affect the young people, the post-martial law babies who grew up with Bagong Lipunan (New Society) songs blaring from jeepney radios and were baby-sat by TV sets? Would they look into the future with the same bright hopefulness of the Grade 11 student seen on YouTube singing praises to the Marcos years?

The hushed audience listened to survivors of two decades of repression – the silencing of the press, the scuttling of the rights of workers and peasants, and the imposition of one-man rule through the use of military force.

Ed Muyot, who was with the Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship in Toronto, was a high school student in the Philippines when he was arrested and tortured. YSH CABANA

Millennials, those born between 1981 to 1996, such as Robyn Matute, a film studies graduate, and Stefanie Martin, a masters degree-holder in archival research, had questions in their eyes, wanting to know more about what happened during that period of chaos.

Most of the young people who attended the forum hadn’t been born yet to have memories of martial law in the Philippines, but they were evidently touched by reminiscences of their elders who suffered under the dictatorship.

One after the other, speakers recalled their experiences of torture in the hands of the military, the loss of political and civil liberties, the repression of those who made attempts to disagree with the state, and the worsening of the country’s economic condition on account of Marcos’ cronyism.

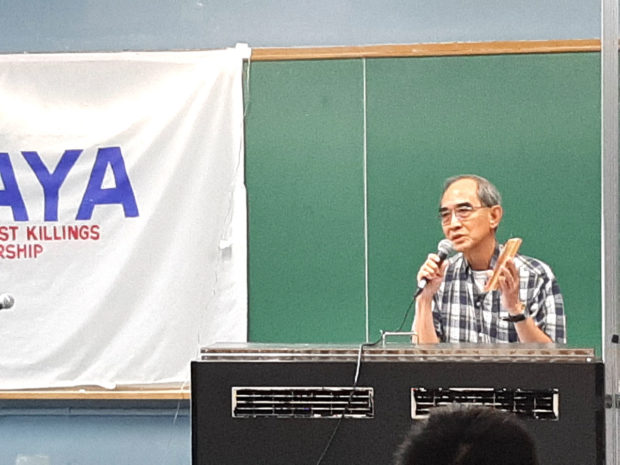

Journalist Hermie Garcia, a former political prisoner, recalls his experience under the Marcos dictatorship. LUI QUEANO

Journalist and community activist Mila Astorga-Garcia, still shudders at the thought of those dark hours in the mid-1970s, when she and her husband Hermie Garcia, now publisher and editor of the Toronto-based Philippine Reporter newspaper, were detained on trumped-up murder charges.

“My ordeal didn’t just start in Camp Crame,” Mila Astorga-Garcia said, “I was arrested and forcibly detained three years prior to the imposition of martial law in 1972.”

In 1969, the newly-married couple — Astorga, a senior Anthropology student at the University of the Philippines, and Garcia, president of SCAUP, a campus progressive organization — decided to start a newspaper, Dumaguete Times, to document the plight of sacadas (sugar workers) in Negros Oriental in south-central Philippines.

“It was a time of ferment—we were writing stories about landgrabbing and how sacadas were being exploited by big sugar plantation owners, forced to work in the fields for long hours only to be paid measly wages.”

The night of their arrest, Astorga-Garcia was handcuffed and hustled to a huge deserted mansion out in the sugar fields, fearing for her life. “Although they did not hurt me physically, they tortured me mentally.”

Rick Esguerra of Philippine Solidarity Group warns audience at Ryerson University of the dangers of authoritarianism. YSH CABANA

The Garcias were freed after the National Press Club and international media groups protested. They would be re-arrested and detained subsequently after martial law was declared. Hermie was confined for six and a half years while Mila, freed after the first hunger strike, would later support her family by juggling three jobs.

Hermie Garcia pointed out that while democratic institutions were dismantled under authoritarian rule, the non-state-controlled press, mostly underground, would continue to fight for human rights. His newspaper, The Philippine Reporter, continues this tradition with its analyses and reportage of basic rights issues.

“We never wavered, as we should not waver today. We must stand firm against all forms of dictatorships.”

Survivors of the martial law years—Rick Esguerra of the Philippine Solidarity Group, and Ed Muyot of Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship (CAMD)—said that looking back in history could help the present generation become aware and vigilant.

“We were among the first of Asian nations to rise up against an oppressive colonial regime,” said Esguerra.

Muyot, now 66, was still in high school when he was arrested, detained, and tortured for organizing student demonstrations. Forced to flee to Canada, he helped organize CAMD, whose spirit, he said, young people should re-ignite, this time against President Duterte.

Lui Queano and Rhea Gamana of Malaya Canada sang protest songs, among them “Do you remember the 21st night of September?,” to the beat of empty plastic buckets and egg shakers. It was a night to remember, even 47 years after.