Fil-Ams celebrate Manila House, a literary landmark in Washington, DC

A group of Filipinos stand in front of a row house identified above the entrance as “Manila House” with the address numbers “2422” lettered on the transom. The photo was taken in 1944, (Source: The Rita M. Cacas Filipino American Community Archives Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries, College Park, Maryland)

WASHINGTON, DC — Historic sites open doors into the past and bring history to life. They provide insights into the stories of those who once gathered in these places, leaving a lasting mark.

Award-winning Filipino American writer Bienvenido (Ben) Santos (1911-1996) wrote about such a place in his book Scent of Apples. It was called Manila House, a three-story building located in downtown Washington, DC about a couple of miles away from the White House.

For nearly 20 years, in the late 1930s through the 1950s, it was “home away from home” for Filipinos who yearned for home-cooked meals and the company of fellow Filipinos. Santos apparently frequented the place while working in the Information Division of what is now the Philippine Embassy.

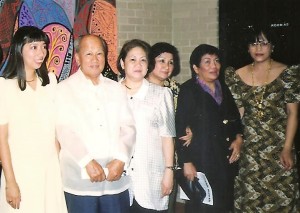

Bienvenido Santos and Philippine Embassy consul general Teresita Barsana during a visit to the Embassy in 1988. INQUIRER/Jon Melegrito

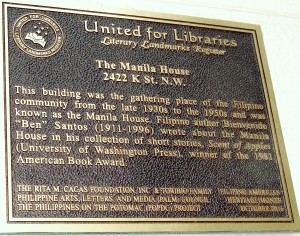

Although Manila House as a gathering place is gone, its memory is enshrined in a bronze plaque on the front of what is now the administrative offices of the St. Paul’s Episcopal Parish. Last year, United for Libraries, a division of the American Library Association (ALA) designated Manila House as a Literary Landmark in honor of Santos. It was the first time such a historic recognition was made in honor of a Filipino American writer, a major literary figure of his time.

Dedication ceremony

On May 6, leaders and members of the Filipino American community, diplomats and dignitaries, students and scholars, converged at the original site of the former Manila House on 24th and K Streets, with a plaque prominently displayed by the front door. They gathered to dedicate the Literary Landmark, one of only four in the nation’s capital.

A plaque glued by the front door enshrines the old Manila House as a literary landmark. INQUIRER/Jon Melegrito

“I never imagined we would get to this day,” said a teary-eyed Rita Cacas, writer and archivist and president of the Rita M. Cacas Foundation, which has been documenting stories of Filipino pioneers in the Washington DC area.

“I first learned about Manila House 24 years ago, in 1993, when I interviewed my father Clemente Cacas and his friends, Fernando Aguilar and Mateo Perez. They described the house as a place for taxicab drivers like themselves to hang out, play cards and attend dances for ten cents on weekends.”

At the dedication ceremonies, she recounted how interviews, painstaking research and some sleuthing led to learning about the row house and, many years later, its exact location.

Cacas, who co-wrote with Juanita Tamayo Lott Images of America: Filipinos in Washington, D.C., said that while gathering materials for the book in 2009, she was informed by Maryland resident Nila Toribio Straka that her grandmother, Asuncion Gaudiel, raised a vegetable garden in the back of the house and cooked the meals.

A few years later, Cacas met Georgetown University Professor Erwin Tiongson and his wife, writer Titchie Carandang-Tiongson, who were putting together a map of places and community sites in Washington, DC that had some connection to Philippine-American history and culture. The result is Philippines on the Potomac, (POPDC), a project co-directed by the couple. It’s a scholarly documentation of Filipino presence and history in Washington, DC in the early 20th century, just after the Philippines was acquired by the US.

Card games and fights

“Though the memories were vivid, the exact location of the Manila House was unknown,” wrote Carandang-Tiongson in a blog post. “It was in May 2013 when my husband found the location of the Manila House by looking it up in vintage directories and newspaper articles.”

“It was so exciting when Erwin called me on May 29, to tell me that he found the Manila House,” Cacas said. She and the Tiongsons visited the old Manila House soon after. The parish priest welcomed the visitors and even introduced them to a parishioner who remembered Filipino-driven taxi cabs parked outside the building.

Writer Bienvenido Santos and members of PALM led by Noree Briscoe (right) at the association’s formal founding in June 1987. INQUIRER/Jon Melegrito

“It was an amazing experience to walk in the same rooms described by Bienvenido Santos in his short story, ‘Manila House,’ wrote Carandang-Tiongson. “Since then we have learned more fascinating stories about this place. I found out that the Visayan Circle of Washington, DC bought the Manila House in 1937 from the St. Stephen’s Club. It was the home of at least one Filipino publication, The Filipino Reporter. Diosdado Yap, the editor of Bataan Magazine and who was also president of the Visayan Circle, entertained frequently at the Manila House, meriting a mention in the Washington Post when he hosted a Filipino delegation from Hawaii. The Post also mentioned card games and fights going out of hand.”

Big surprise

“But the big surprise was in 2015, when we received three small photos of Filipino friends in front of the building clearly marked Manila House,” Cacas pointed out. “So now we have the solid evidence”

For Cacas and the Tiongsons, the next step was to have Manila House designated as a national historic landmark. The National Park Service administers a program that “recognizes historic properties of exceptional value to the nation.”

Filipino American community leaders, scholars and students, diplomats and dignitaries listen to Rita M. Cacas acknowledge the support of the St. Paul Episcopal Parish, which took over the old Manila House. INQUIRER/Jon Melegrito

The requirements, however, are rigorous and the process itself challenging. The group opted, instead, to work with United for Libraries to have Manila House designated as a literary landmark. The Literary Landmarks project commemorates a community building and its ties to a literary figure or prominent author.

Joining Cacas and the Tiongsons in making this happen is Mitzi Pickard, president of the Philippine Arts, Letters and Media (PALM) Council, a Washington DC-based literature reading association. PALM was formed in June 1987 by a group of friends led by writer Noree Briscoe who were inspired by Ben Santos and saw the need for a greater awareness of Filipino novels, short stories, poetry and drama. Santos attended the formal founding of PALM when he was visiting the nation’s capital that summer.

Evangeline Paredes (left) and Nila Toribio Straka share their recollections of the people who used to gather at Manila House. INQUIRER/Jon Melegrito

In her remarks at the dedication ceremony, PALM member and Philippine Historian Dr. Bernardita Churchill recalled the lectures, readings and book signings by Santos during his return visit to Washington, DC in 1988.

“Ben encouraged young Filipino American writers to tell the stories of their sojourn in America, stories that tell of their dreams, hopes and fears as immigrants,” Churchill said. “It is, indeed, fitting that this dedication event honor Bienvenido N. Santos, who continued his association with PALM until his death on January 7, 1996.”

A refuge

After the dedication ceremony, a granddaughter of Gaudiel, who opened and managed Manila House, shared her recollections during a tour of the place. Nila Toribio Straka, 86, said she remembered sitting on her grandmother’s lap in a smoke-filled room, seated around a card table with a dozen men dealing cards, with dozens more standing three deep behind them. “I was about six years old,” Straka recalled. “One night, the police raided the place and arrested 55 people for illegal gambling.”

She described the vegetables from the garden, and how her mom and aunts would help her grandma in the kitchen. “When you walk in, there’s always the strong, delicious smell of pork adobo, and the vinegary taste of sinigang,” she said. “Manila House was a refuge for Filipino sailor boys, a place for them to congregate, where they feel like they have a home away from home.”

Straka also learned later from her parents, pioneers Amparing and Leo Toribio, how they dealt with racial discrimination in what was then a segregated city. “They had to sit at the back of the bus, and they had to walk on the other side of the street if they saw white people walking towards them,” she said. “It’s important that our children and the young people today know and appreciate the struggles our parents and grandparents went through and be proud of our heritage.”

Evangeline Paredes, a native Washingtonian who recently turned 101 years old, also shared her own memories and the “fun times” she had at a place which became the center of community life. She was working then as a secretary to President Manuel L. Quezon. After hours and on weekends, she would go to Manila House and help check in people who came in. “I was so proud to volunteer at the door,” she recalled.

Building community

The afternoon program included a presentation of historic photographs of

Manila House to the Parish, a rendition of Filipino ballads that were favorites of Ben Santos, and an exhibit of old photos and news clippings about the early Filipino pioneers who built a community in Washington, DC.

Leaders and members of the Philippine Arts, Letters & Media (PALM), Philippines on the Potomac, the Rita M. Cacas Foundation and Philippine Embassy officials pose for a photograph in front of the old Manila House. CHRISTOPHER COOK

“It’s great that all the clues about Manila House are being pieced together,” said Gem Daus, an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland. “Now we have a place we can preserve. Our history is usually forgotten. This is our attempt to say, ‘Hey, we’ve been here for a while, thriving and building community.’ This plaque and the pictures prove that Manila House was here.”

“The weight of this bronze plaque encompasses all of the souls that came to the Manila House more than 80 years ago,” said Cacas, when she first unveiled the plaque at a community symposium last November.

At the dedication in two weeks ago, Cacas added: “It means a lot for the next generation of Filipinos to remember this spot, which commemorates not war but a community of people, people who stopped in this place 80 years ago on their way to work and met up with friends. People like Fernando Aguilar, Mateo Perez, Clemente Cacas, Ben Santos, Nila’s grandmother. They mattered and we are going to remember them.”