PH Mental Health Law: A bright beginning for Filipinos

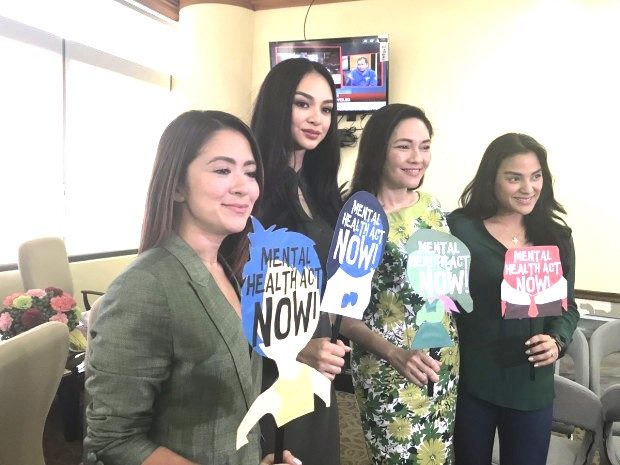

Senator Risa Hontiveros is flanked by supporters of the mental health bill, actress Antoinette Taus, Miss International Kylie Versoza, and Jerika Ejercito. INQUIRER FILE

Dr. John Mackenzie spoke of a patient, Ms. P. who allegedly suffered from some kind of a “respiratory distress,” we might dub today as asthma? Ms. P. professed that she was allergic to flowers, specifically roses.

On one occasion, Ms. P. came to see Dr. Mackenzie. As Ms. P. walked into the consultation-room, she noticed a huge bowl of roses on the table, took one look at the flowers… gasped, then went into a paroxysmal reaction: coughing; swollen nostrils; a tight chest.

The doctor led her into the treatment room; the nurse immediately gave her a hypodermic injection as she was wheezing heavily.

When Ms. P. stopped wheezing, she reproached the doctor, “How could you be so thoughtless, you know how sensitive I am to roses?!” Whereupon the doctor went toward the flower vase, snipped a “rose bud,” and tore it into little pieces. It was a bouquet of paper roses!

He then whispered to Ms. P. that the injection given her was pure sterile water! (This obscure, but oft-cited case is attributed to John Mackenzie, a surgeon in Baltimore in the 1880s).

Was Ms. P.’s case purely medical, psychological, psychiatric, or mere ideational?

Atypical

Ms. P’s case seems atypical,but from a clinician’s perspective it does present us the general potential complexities in dealing with a livinghuman being associated with one’s particularmental, physical (or sometimes even spiritual) state of health.

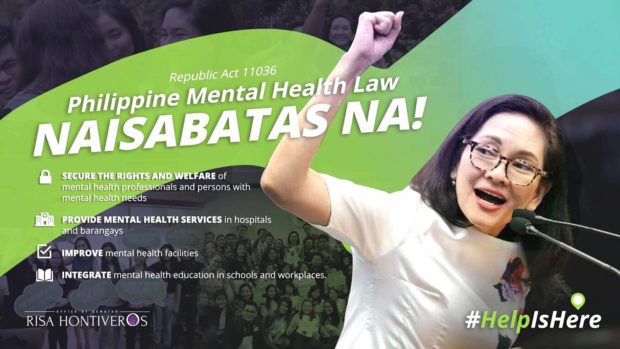

“No longer shall Filipinos suffer silently in the dark. Mental health issues will now cease to be seen as an invisible sickness spoken only in whispers,” said Senator Hontiveros, former chair of the Senate committee on health.

Hontiveros is the proponent of the newly signed Mental Health Law of the Philippines, or Republic Act 11036, which aims to give better access to mental health care among Filipinos. The law was signed on June 21, 2018.

The first Mental Health Act was filed three decades ago in 1989 by then Senator Orlando Mercado; there were at least 16 other bills before becoming a law.

The law seeks to provide mental health services down to the barangay level, and integrate mental health programs in hospitals. It also seeks to improve mental health facilities and to promote and integrate mental health education in academe and workplaces.

A spokesperson for a coalition group jubilantly declared, “We say goodbye to taboo, superstition, and myths about mental health issues now that services are made accessible for all citizens… protects rights and welfare of people with mental health conditions, shifts focus of care to the community, improves access to services…”

Allocation

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported in 2007 that the Philippines spends about 5% of the total health budget on mental health, where substantial portions of which are spent on the operation and maintenance of mental hospitals. This means that only a marginal portion is allotted directlyinto patients’ management.

However, with the new law, this would likely change. The total 2018 budget of the Department of Health (DOH), including budgetary support for government corporations, is Php171.09 billion (US$3.2 billion), according to Senator Legarda, chair of the Senate Committee on Finance.

The new law specifically states that the amount necessary for the initial implementation of the provisions of the law shall initially be charged against the current year’s appropriations of the DOH. Thereafter, five percent (5%) of the incremental revenues from the excise tax on alcohol and tobacco products collected shall be earmarked (continually) pursuant to Republic Act No. 10351.

The DOH has a very broad mandate: formulate;develop; and implementa national mental health program based on the policy and objectives provision explicitly defined in the law. The author advocates that this very broad mandate be shared with the Psychological Association of the Philippines (PAP).

PAP is the largest collegial organization of mental health professionals, providers, and researchers equivalent to that of the American Psychological Association(APA). PAP was founded in 1962, with the mission to “excellence in the teaching, research, and practice of psychology, and its recognition as a scientifically oriented discipline for human and social development.”

Moreover, empirical studies suggest that many practitioners of healing estimate that 50% to 80% percent of patients who consult medical doctors suffer from functionaldisorders. Disorders of this kind are those thought to originate from the mind for which no organic or physiological basis can be established lucidly, demarcated or verified.

The rub

The Philippines has a population of 105.1 million with a ratio of human resources workingin mental health at 3.5:100,000 where rates are particularly low for social workers and occupational therapists, reported WHO in 2007. Reports also show that currently there are 700 Filipino psychiatrists and a thousand psychiatric nurses practicing.

The rub is, out of the 700 psychiatrists, more than 50% work in for-profit mental health facilities and private practice. The distribution of human resources for mental health tends to favor that of mental health facilities urban areas; far-flung places are often left without any mental health assistance.

The Mental Health Atlas of WHO reported a decade ago that the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 of the general populations is similar to the majority of countries in the Western Pacific region, which is about average for lower middle resource countries.

This is probably acceptable in the Philippines if the number is equitably distributed. The seven hundred psychiatrists would not even suffice if we “equally” allocated one Filipino psychiatrist per island in an archipelagic country of 7,107 islands (during low-tide, quips a kibitzer friend).

We are reminded that studies show one in five Filipino suffers from some sort of a mental health problem or issues. The National Statistics Office (NSO) reported in 2016 that 88 cases of mental health issues were reported for every 100,000 Filipinos, a conservative number that is probably reflective of the more profound conditions.

Moreover, adding to the number of psychiatrists available; the number of psychologists practicing within the realm of mental health (clinical, developmental, educational, social, health, community, and forensic), and other allied mental health professionals or providers (social workers) could somehow alleviate this paucity of mental health professionals.

It should be also noted that the Filipino psychologists were ‘professionalized’ barely eight years ago upon the passage of The Psychology Law of the Philippines or Republic Act No. 10029 on March 16, 2010. Are psychologists now at par — “professionally” — with psychiatrists? The contention remains, unless the precise pathological cause is lucidly, definitely resolved. This is another very interesting piece to write, again according to a kibitzer friend.

We are forewarned: The role played by physicians, psychiatrists, and psychologists in mental health is not devoid of controversies which, a kibitzer friend quips, would be another interesting topic of its own to write about as hinted in Ms. P.’s case.

Advocates

Before the Philippine Mental Health Law was finally signed, advocates cried that, the country had gargantuan mental health problems. The truth is, this is the same sentiment or tone echoed even among developed countries.

Different groups, coalitions, and organizations used to clamor that, “Aside from cases of psychiatric conditions, there’s the lack of mental health professionals, facilities, funding, and a national law.”

Filipinos now have the Mental Health Law. Where do we start?

Maybe in the doorsteps of the academe…“where the Filipinos are still developing beings who are in a unique, often precarious, relatively short phase of human development within a delicately prescribed timeframe…”

One bitter-sweet caveat arises though: As with any new law, the bigger challenge lies in the implementation. Advocacy never stops, it only pauses.

In quo et nos incipere?

Dr. Carson-Arenas is a Fellow of the Philippine Psychological Association, Certified Clinical Psychology Specialist, and a former university research director. He is a Behavior Analyst Specialist in Nevada, an educator, clinician, researcher, consultant and a published author. The father of Dr. Carson-Arenas, Dr. Arnolfo A. Arenas, Sr. was a neuro-psychiatrist at the Johns Hopkins who died many years ago. Please e-mail at: docaggie5@yahoo.com.