It’s a confrontation one would expect under a president who inspired a bloodbath, who suggested to Filipino soldiers that it’s okay to rape and who recently offered virgins to visitors.

The video of the press conference shows Rappler reporter Pia Ranada calmly asking Duterte: “Sir, you said in your speech that the SEC ruling on Rappler is not an issue of press freedom. But at the same time in you speech you were giving comments on the media about Rappler and Inquirer na sumusobra na kami (we’re abusive). What does that mean, sir?”

The response from a leader who has shown repeatedly that he just can’t stand being challenged in public, especially by women: a barrage of angry curses, lies and insults.

“Eh bastusan na e di bastusan tayo… Mga gago kayo.. Katagal na ninyong lumeleche sa amin. Pati tae na nga tinatapon ninyo sa amin.” (If it’s about insults, then let’s insult each other. You are all stupid. You’ve been disrespecting us for a long time. You even throw shit on us.)

As Rappler CEO Maria Ressa described in a Facebook post: “Pia Ranada, a wisp of a girl, stood up and treated our cursing president with respect, even as she asked tough questions.”

The incident also highlights a tradition in Philippine journalism: women reporters, writers and editors standing up to thugs and tyrants.

Before Ranada’s poised and courageous performance in the face of yet another Duterte tantrum, there have been many other Filipino women journalists who didn’t back down and who bravely faced off with bullies and demagogues.

Here are some of them:

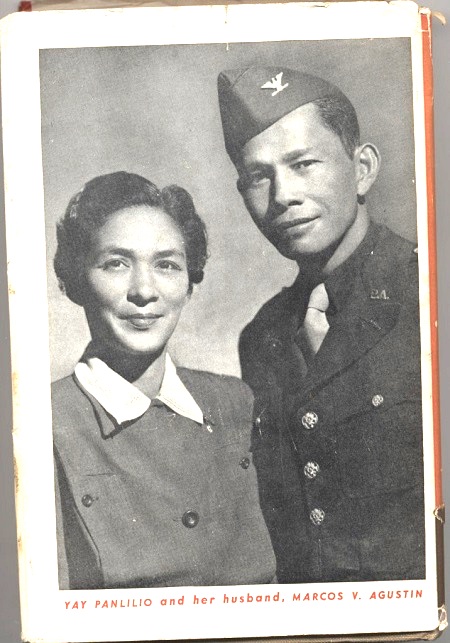

Yay Panlilio

Yay Panlilio was a famous newspaper journalist in Manila when the Philippines endured a serious form of bullying with the Japanese invasion in 1941. That derailed her journalism career. But she pivoted to a bold new role by joining the resistance

Yay Panlilio with husband Marcos Agustin; Panlilio was a journalist who became an anti-Japanese guerrilla.

movement. Actually, she wasn’t just a member of the resistance — Panlilio became known as Colonel Yay, the leader of one of the guerrilla units that worked to defeat the Japanese imperial forces. She later was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom and published a book, The Crucible, about her role in the anti-Japanese movement.

Roz Galang

Roz Galang was a prominent reporter with the Manila Times when Ferdinand Marcos, the dictator Duterte idolizes, declared martial law in 1972. When the thugs took over, Galang took her journalism career underground, serving as editor of underground publications geared to workers and urban poor communities. “She would not have exchanged the fulfillment she was enjoying then for the perks and privileges of an establishment journalist,” her fellow journalist-activist Carolina Bobi Malay recalled in a tribute to Roz on the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani site. “No air-conditioned offices, no expense accounts, no rubbing elbows with the rich and famous. No salary, and often, not even a pseudonym for a byline. It was enough that for the first time in their lives, ordinary people found themselves being written about admiringly, in language they could understand.”

Roz Galang died of cancer in 1998.

Carolina Malay Like Roz Galang, Bobi Malay left a cushy, even glamorous, life as a Manila reporter to join the underground resistance against the Marcos dictatorship. In 1986, after years of living underground, she surfaced to join Satur Ocampo and Tony Zumel, two other former journalists who joined the movement against the dictatorship, in representing the National Democratic Front in peace talks with the newly-installed government of Cory Aquino.

Fides Lim

I’ve written about Ditto Sarmiento who died after a grueling stint in a Marcos prison and who inspired the famous slogan, “Kung di tayo kikibo, Sinong kikibo!” (If won’t act, who will?) We should also honor his staff, including managing editor Fides Lim who was arrested with Sarmiento during the crackdown on the UP publication. Lim went on to become a full-time activist against the dictatorship.

Malou Mangahas

Malou Mangahas faced off with two bullies, first when she was a student leader at UP Diliman and later as a professional journalist. She served as editor of the Philippine Collegian in 1979, a constant target of the Marcos regime. She also helped lead the campaign to restore the UP student council, eventually becoming its first chairperson since it was banned by the dictatorship. After Marcos came Joseph Estrada. Mangahas was editor of the Manila Times when it became a target of the Estrada administration.

Sheila Coronel

Sheila Coronel, now the academic dean of the prestigious Columbia School of Journalism and winner of the Ramon Magsaysay Award, was known for leading the trailblazing Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, which exposed politicians and military men involved in illegal logging and other cases of political corruption in every administration after the fall of Marcos. As the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation said in its citation, the PCIJ “spared no legitimate target.”

Letty Magsanoc

Letty Magsanoc was another editor who stood up to Marcos the dictator. She was forced to resign as editor of Panorama, the magazine of the Manila Bulletin, for publishing hard-hitting articles critical of the dictatorship. She later joined Eggie Apostol in launching the Philippine Daily Inquirer shortly before the snap elections that eventually led to the end of the dictatorship.

Marites Vitug

Marites Vitug took on a powerful political force in the country: illegal loggers. Her reporting on the corruption and abuse in the logging industry has such an enormous impact she was featured in a 1991 special report by US journalist Peter Jennings called ‘Dangerous Assignments.”

Chit Estella

Chit Estella belonged to the generation of journalists who began their careers during the dark years of the Marcos regime. She helped turn the PCIJ into a reporting powerhouse in the post-Marcos era and served as Malou Mangahas’ gutsy managing editor at the Manila Times. In 2008, she helped launch Vera Files, another hard-hitting investigative reporting organization. She was killed in a road accident in 2011.

Women Writers in Media Now (WOMEN)

Women journalists during the Marcos regime were routinely summoned to military interrogations where they were forced to explain articles critical of the dictatorship. Eventually, a group of them grew tired of the harassment. A group of journalists, led by Paulynn Sicam, Marra Lanot, Ceres Doyo, formed Women Writers in Media Now, or WOMEN, to speak out against the regime’s intimidation tactics.

In fact, the first protest I attended as a teenager was led by WOMEN who staged a picket followed by a march right in front of Camp Aguinaldo. This was in 1982 when Marcos was still at the height of his power. I remember feeling inspired by the courage of these women writers who dared to take a stand right outside one of the dreaded power centers of the fascist regime.

Fast forward to January 2018, to the Rappler #BlackFridayForPressFreedom rally two weeks ago in Quezon City. I imagine that among the protesters that day were young Filipinos who listened intently as Rappler CEO Maria Ressa declared: “We’re going to hold the line. We’re doing journalism. We’re speaking truth to power. We’re not afraid and we won’t be intimidated.

This list is incomplete and too focused on Manila. I apologize to friends in media in Mindanao, the Visayas and Northern Luzon. There are, to be sure, many more women journalists and writers who stood up to all forms of bullying and demagoguery in other parts of the country.

One thing is worth noting. In every confrontation with thugs and tyrants in the history of Philippine journalism, the cause of press freedom prevails. And the bullies go down in defeat.

Visit the Kuwento page on Facebook.