‘Kung di tayo kikibo, sinong kikibo?’ The hero behind the slogan

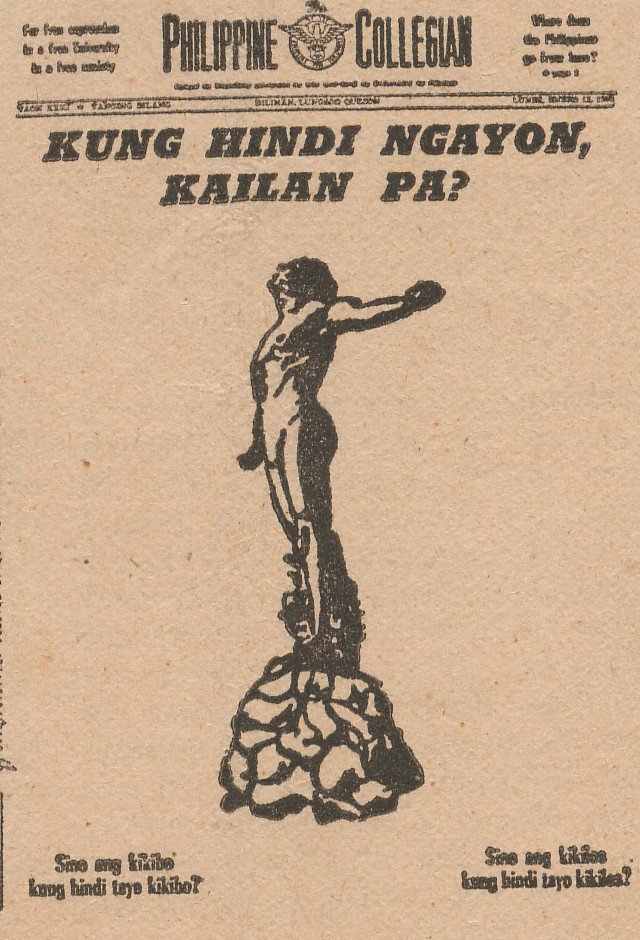

In November 1977, students on the UP Diliman campus picked up copies of the Philippine Collegian with a stunningly defiant front page.

It featured an illustration of the Oblation, but instead of his arms outstretched, UP’s famous symbol had his fist raised to the sky, having broken free from shackles.

Emblazoned on the cover was this message: “Para sa iyo, Ditto Sarmiento, sa iyong paglilingkod sa mag-aaral at sambayanan.” (For you, Ditto Sarmiento, for your service to the studentry and the nation.)

November 11 marks the 40th anniversary of the death of one of the most courageous young Filipinos to defy the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. It’s a tragic story worth highlighting today as the nation, especially young Filipinos, face off with another fascist regime.

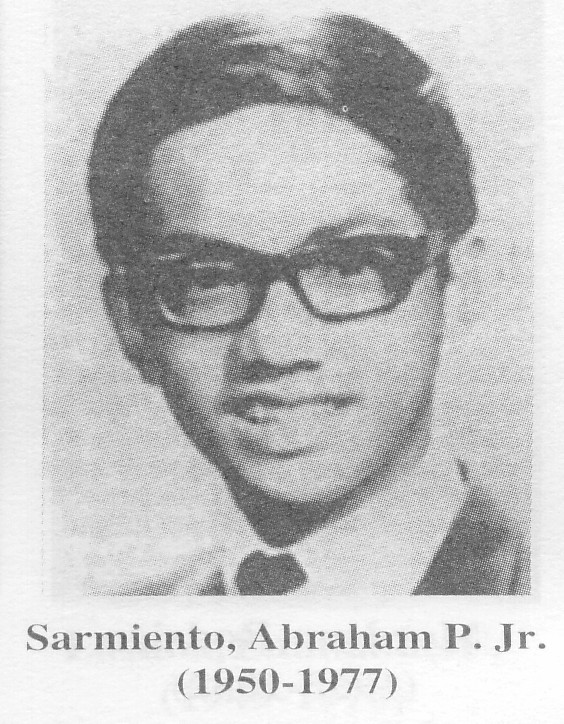

Abraham “Ditto” Sarmiento Jr. was only 27 when he died after spending seven grueling months in a Marcos prison.

His “crime”: daring to speak out against a dictator at the height of his power and ruthlessness.

Sarmiento became editor of the Philippine Collegian in one of the toughest and most dangerous times for journalism in the country. Major newspapers and TV news broadcasts were censored heavily. In the mid-1970s, just a few years after Marcos seized power by declaring martial law, any form of criticism of or opposition to the regime could mean jail or even death.

In this grim situation, the UP Collegian played a pivotal role. In the early years of dictatorship, the student newspapers served as a voice of defiance. And under Ditto Sarmiento, the Collegian grew even more daring.

“The time has come for us to take action and not lie silently about as our rights increasingly become trampled upon,” he wrote in a 1976 editorial. “The time is now, for if not now, when?”

Sarmiento’s staff followed this up with what eventually became one of the most famous Collegian front pages in history. It featured an illustration of the UP Oblation with the banner: “Kung Hindi Ngayon, Kailan Pa?” [If Not Now, When?] At the bottom of the page the Collegian asked: “Kung Hindi Tayo Kikibo, Sinong Kikibo? Kung Di Tayo Kikilos, Sinong Kikilos?” [Who will speak up if we do not speak Up? Who will act if we do not act?]

It didn’t take long for the dictatorship to strike back. In January 1976, Sarmiento was arrested by the regime. He had been a frail young man and his health deteriorated in his seven months in a Marcos prison.

He never fully recovered. Ditto Sarmiento died a little over a year after being released from prison.

It must be pointed out that the story of Ditto Sarmiento took place in a radically different era. This was the time before Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and the World Wide Web.

Today what happened to Ditto Sarmiento, his acts of defiance and subsequent imprisonment and death would have immediately sparked heated discussions online. It would have led to blog posts and memes and extensive coverage by the mainstream media. His arrest and subsequent death probably would have led to public protests.

That was not the situation in the mid-1970s. Sarmiento and the UP Collegian were fighting back in a time of silence and fear. For the most part, they were alone and isolated. We can just imagine how Ditto Sarmiento’s death affected his fellow students who had to continue their work at the UP Collegian. For speaking out against the regime, their leader was harassed and thrown in prison, which led to his death. There was no public outcry. They were on their own.

And yet they honored their fallen editor with yet another act of defiance. Forty years after his death, it’s time to honor him once again:

“Para sa iyo, Ditto Sarmiento, sa iyong paglilingkod sa mag-aaral at sambayanan.”

Visit the Like the Kuwento page on Facebook.

On Twitter @boyingpimentel