UST in World War II, a different kind of education

A LIFE Magazine cover showing The Dominican university transformed into an internment camp with only one curriculum, which was survival..

When Japanese airplanes started bombing key targets in and around Manila in early December 1941, the administration of the University of Santo Tomas decided to play it safe and close the campus. Unfortunately, the closure of the prestigious university lasted for several years. Although the traditional university was closed, the 60-acre campus was given a different role.

In early January 1942, the Japanese Department of External Affairs renamed the university the Santo Tomas Internment Camp or STIC. The decorative iron fences that outlined and separated the campus now became prison walls.

At the time of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in December 1941, there was a significant number of American and British civilians in the islands especially in Manila. Most of the civilians were conducting business during the era of the Philippine Commonwealth. Some of the businessmen and their families had decided to return to their home countries when the relationship between the United States and Imperial Japan had deteriorated in 1941. Approximately 4,000 allied civilians including women and children remained in the Manila area.

‘Enemy nationals’

The Japanese occupation forces in the Philippines designated the civilians as “enemy nationals.” They were ordered to pack a few belongings and proceed to STIC. In a short time, the population of STIC grew to 3,800 men, women, and children. The main building of UST now became a dormitory that separated the men and women. The Dominican university that dated to 1611 now had only one curriculum, which was survival.

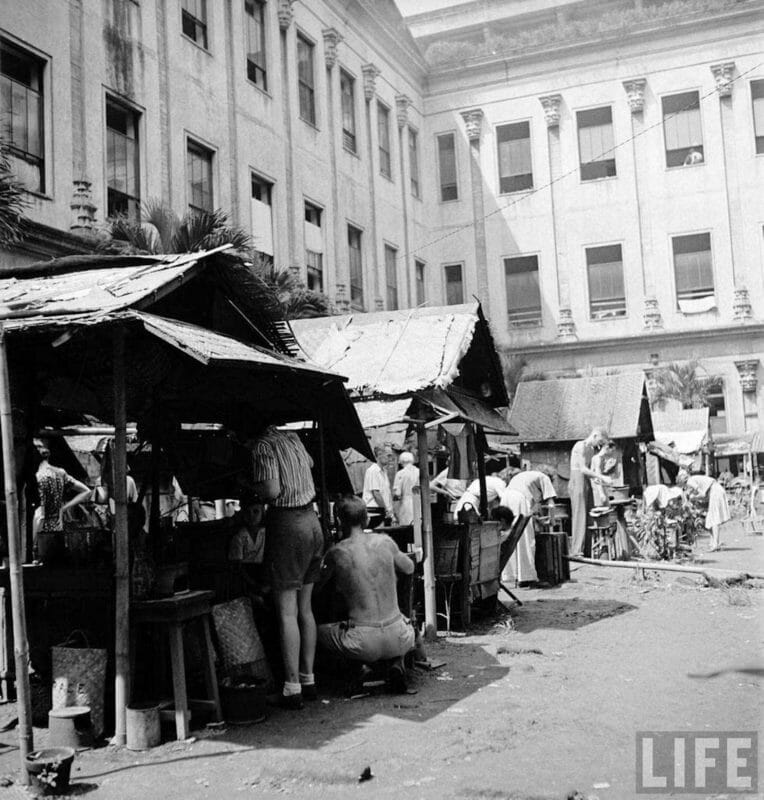

As the number of detainees swelled at STIC, the campus started looking like a makeshift village. There were flimsy wooden buildings constructed on the grounds of the school. The detainees formed committees to provide schooling for the children, adult education classes, and general operations in the camp. In a short time, STIC resembled a town with a market for buying and selling goods. There were even entertainment and sports.

There were many challenges and problems among the detainees. From the beginning, there was a class system. A few of them had been able to bring money or other valuables with them to the camp. They could use the currency to supplement their diets and needs at the marketplace. The detainees without currency were locked out of this market. Wealthier internees who did not have money with them could gain credit based on expected future payoffs. There were crimes and vices committed by some of detainees at STIC.

Help from Filipinos

Fortunately, the Filipino friends of the detainees assisted their compadres at STIC. The smuggling of food and medicine into the camp was common. Also, the Filipino friends were an excellent source of news especially on the progress of the war in the Pacific. In some cases, the Filipinos risked their own lives to help the prisoners.

Although STIC was established for “enemy nationals,” there were 75 Prisoners of War at the camp. Eleven U.S. Navy nurses, who were working at a hospital when the Japanese captured Manila, were transported to STIC. Also, 64 U.S. Army nurses, who had served on Bataan and then Corregidor, were assigned to STIC. The nurses were an essential part of the limited health care system at the camp.

There were many problems with the administration of the camp. The Japanese officers and guards were indifferent to the needs of the detainees. Medicine and medical supplies were always in short supplies. They daily food rations were inadequate for the number of detainees. The problems in the camp were exacerbated over time.

By 1944, control of the camp was reassigned to the Imperial Japanese Army. The change in rule led to more restrictions like frequent roll calls. Malnutrition and death became constant occurrences. The detainees were reduced to one meal a day of vegetable gruel. The morale of the camp plummeted. Some of the prisoners just gave up hope of a rescue.

Rescue

Starting in late 1944, American airplanes started flying over the camp. The morale of the detainees improved dramatically. With the renewed excitement, there came new fears. Many of the detainees thought that the Japanese Imperial Army would just execute them. The only thing that the prisoners could do was wait and see.

When the American Sixth Army landed at Lingayan Gulf on January 9, 1945, one of the urgent priorities was the rescue of the Prisoners of War and the allied civilian detainees. Quickly, a couple of “Flying Columns” headed to Manila to rescue the detainees. Essentially, these fast-moving columns were behind enemy lines.

On February 3, 1945, several U.S. Army tanks came crashing through the STIC gates. The detainees were stunned by the dramatic entry. After a clash with the Japanese guards, the U.S. soldiers negotiated a Japanese withdrawal to prevent any bloodshed of the detainees. The STIC prisoners were now free.

General Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the American forces in the Pacific, visited the freed STIC detainees on February 7, 1945. The general praised the courage and tenacity of the detainees. Most of the former prisoners that General MacArthur greeted were emaciated, malnourished, and suffering from chronic and acute medical issues. Over time, most of detainees were able to make a full recovery, and the University of Santo Tomas returned to its original academic mission.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is Public Historian and a seasonal park ranger in interpretation for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. He can be contacted at: flakedennis@gmail.com