Is US headed for worst nursing shortage?

We live in a country with the third highest population in the world. Over 320 million people live here, and vital to the health and wellbeing of each one of us are the 3.9 million registered nurses who keep our hospitals, nursing homes, and doctor’s offices running.

But, what does the next five years hold for the profession, and how will the industry deal with an aging population and workforce?

690,000 staff shortage

The American Nurses Association (ANA) predicted that 1.1 million new nurses would be needed by 2022, both to fill the employment gap created by a nursing workforce approaching retirement and a growing over-65 population. Individuals in this demographic cost hospitals up to three times more ($18,424) than working-age individuals ($6,125) on average.

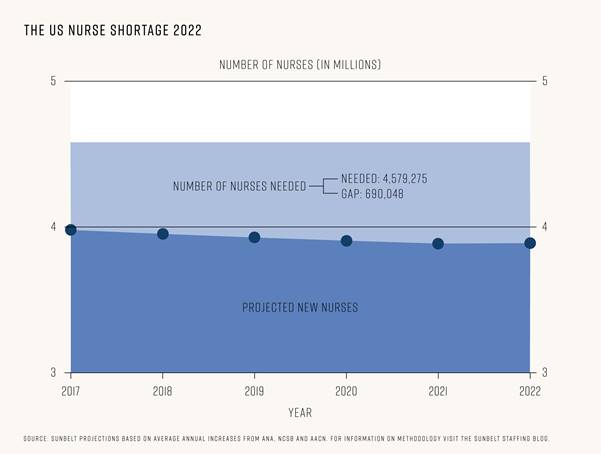

Combining the ANA’s projections with current nurse numbers and retirement predictions, we calculated that the country will need 4,579,275 nurses in total by 2022 to keep up with required demand.

To get a picture of just how close we are to hitting that target, we analyzed data from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSB) to calculate an expected workforce figure based on current graduation and immigration trends.

Worryingly, our calculations revealed that only 3,889,227 registered nurses may be working in the US by 2022. That total includes 457,413 new nurses from a combination of new graduates and foreign-educated nurses. After retirements, that leaves a massive employment gap of 690,048 nurses between the required and expected workforce. So why is there such a disparity?

An aging workforce

Projections from the American Nurses Association’s predict that by 2024, 700,000 nurses will have retired. That’s an average of 100,00 a year, meaning by 2022, up to 500,000 nurses may have left the workforce.

These astounding figures have occurred because of many long-term factors. Firstly, nurses typically stay in their jobs a long time. This has meant, historically, there can be sustained periods when it is difficult for new nurses to find work because of a lack of fluidity in the workforce.

Technology has also made the physical parts of nursing less intense, meaning nurses have been able to work longer than in the past. Additionally, the 2008 recession forced many of the baby boomer generation of nurses who had previously planned on hanging up their uniforms to hold off, but over the next few years they will start retiring as well.

With a generation now set to retire in bulk, now is the time for new nurses to enter the workforce. Millennials are predicted to be twice as likely to be registered nurses than the baby boomer generation, so is the system set up to take this influx of new young nurses?

A struggling education system

The biggest challenge in recruiting, training, and employing a generation of new nurses is the education system’s ability to cope with the volume of applicants. While we have some of the finest institutions in the world, many are simply struggling to accommodate the number of qualified applications they receive every year.

In 2016, there were 65,138 graduates in entry level nursing programs*. To predict the total number of graduates by 2022, we looked at the average annual increase (2,455) to project a cumulative total of 442,383 new nurses in five years’ time.

This figure simply isn’t high enough to meet demand. Thankfully, there is plenty of interest from qualified applicants, but work still needs to be done to ensure schools have the facilities and staff to take them on.

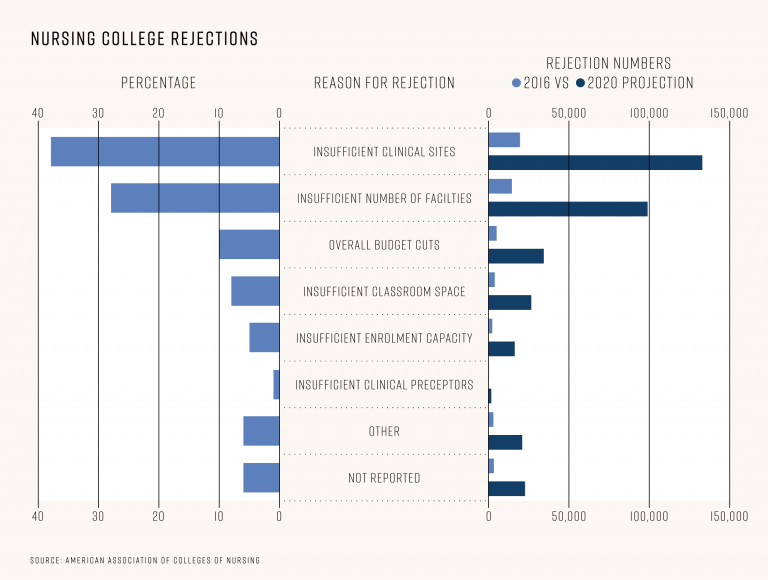

52,208 applicants who were fully qualified for entry-level nursing programs were rejected in 2016. Based on our projections, that could mean a further 354,569 more qualified applicants getting rejection letters by 2022.

In a survey of nursing colleges by the AACN, the reasons institutions gave for rejecting candidates ranged from having insufficient clinical sites (37.5%) to an insufficient number of faculty (27.9%). Some of the other reasons included: overall budget cuts (9.7%), insufficient classroom space (7.5%), and insufficient enrolment capacity for specific programs (4.6%). Put simply: Schools want to take on more nurses, but to do so, they may need support.

We analyzed data from the HRSA on the grants they award to assist nursing programs every year and the numbers are staggering. Overall funding to nursing programs has hit an astounding $62 million in 2017 already, compared to just $243,000 in 2008. HRSA grants are awarded to “organizations to improve and expand health care services for underserved people.” This huge funding increase is a direct indicator of just how much financial support nursing programs today need just to survive, and these funding levels may need to grow even more if the sector is to thrive.

More foreign nurses?

One partial solution to the impending crisis could be to increase the number of internationally educated nurses we allow into the country. America has a long history of welcoming nurses from Canada, Mexico, and many other countries from all over the world. It is, however, hard to know what to expect from 2017 and beyond, with regulations on the H1-B visas nurses require to apply for work in the country already being tightened by the current administration.

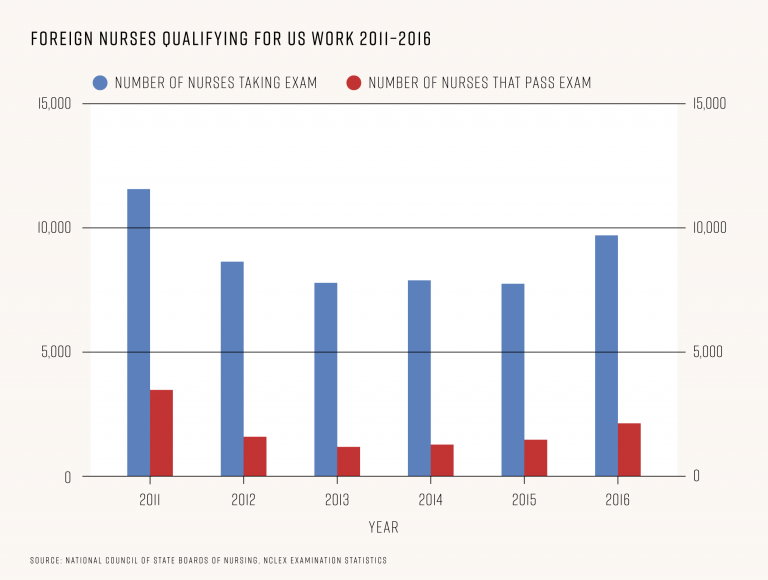

Internationally educated nurses are not only required to apply for visas, but to take the NCLEX examination, which determines if they are prepared for entry level nursing in the US. To begin understanding how many new foreign nurses start work in the country each year, we analyzed examination statistics from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing which gives us a picture of how many foreign educated nurses are applying to work here, and how many are successful in their application.

The number of internationally educated nurses taking the NCLEX examination for the first time hit a five-year high last year: 11,569 took the exam, 4,495 (39%) passed it. Despite the year on year growth however, it is still well behind the 20 year high of 2007, when 33,768 internationally educated nurses took the exam and 17,559 (52%) passed it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, pass rates are lower for internationally educated applicants than those educated in the US. The scale of the difference is surprising though. In 2016, only 38.85% of internationally educated nurses passed the exam first time, compared to 85% of those educated in the US.

Whatever the solution is, it’s clear there needs to be drastic changes to meet the demands of our country. Whether that means increasing federal funding to colleges so they can take on more students, a system more reliant on travel nurses who can move to meet demand in different areas at different times, or relaxing immigration requirements, something needs to happen soon if we want to avoid the potential 690,000 nurse shortage nightmare just around the corner.

For more data analysis and graphics, including analysis of huge rises in federal HRSA grants9 given to nursing programs since 2008, visit the Sunbelt Staffing blog at :

https://blog.sunbeltstaffing.com/nursing/the-future-of-us-nursing-a-690000-staff-shortage/