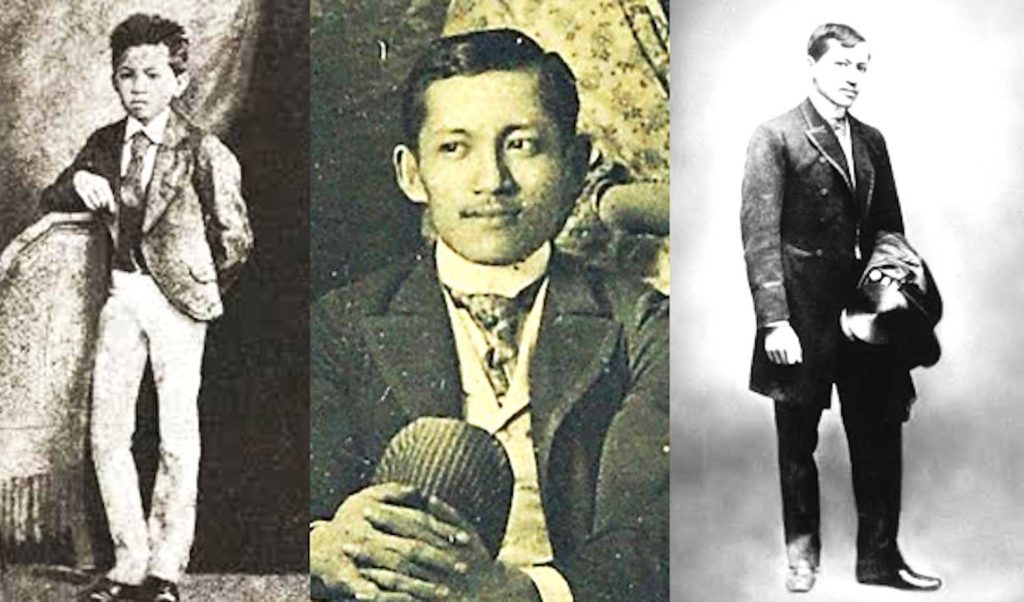

Jose Rizal, from youth to national hero.

NEW YORK—June 19 (“Juneteenth”) is now a federal holiday. On that date, in 1865, after the surrender of the Confederacy at Appomattox, Virginia, African-American slaves were informed that the Civil War had ended and that they now could cast off their shackles and be free. The moment came more than two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued on January 1, 1863, by President Abraham Lincoln.

Juneteenth has been celebrated unofficially in many predominantly Black communities for quite a while now, but with the murder of 46-year-old George Floyd by Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis Police officer (since convicted), in May 2020, thousands in the United States and around the world marched in protest, not just against Floyd’s murder but the killings of other Black citizens, e.g., Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Daunte Wright. The protests and the intense media coverage revivified the Black Lives Matter movement. And provided the decisive push to render the Juneteenth commemoration official.

June 19 is also the day in 1861 when José Rizal was born, to Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso, the younger of only two males in a family of 11 children, in the town of Calamba, Laguna. Considered unofficially as the country’s national hero—no government declaration has been made regarding this designation—Rizal has come to represent the apogee of the nation’s aspirations: a genius and polymath, a fitness buff, a scientist cum pacifist, a writer and artist, and an untiring reformer. And the fact that he was of mixed race—Chinese, Spanish, Malay—rendered him a true exemplar of the country’s bloodlines.

One could say with justification that the protest against Spanish tyranny he so eloquently limned in his writings could be summed up using the vocabulary of today, that Brown Lives Matter, that the Guardia Civil (the police of the colonial period) be defunded.

Rizal’s fame goes beyond national boundaries, notably in Indonesia. When President Sukarno spearheaded the nationalist movement against Dutch colonial rule, he would often mention Rizal in his speeches as one of the heroes fighting for the freedom of Asian peoples, citing him alongside Sun Yat-Sen and Mahatma Gandhi. He said this about Rizal: “You know the history of the famous leaders of the Philippines. They were all leaders who opposed Spain. The name Dr José Rizal, for instance, who was executed by the Spaniards without due process of law, his name is sweet in our memory. He was the great leader of the Philippines who fought against the orthodox Spanish imperialism.”

Young Indonesian writers and scholars, who came of age during the Japanese occupation of their country during World War II and came to be known as the 1945 Generation, grew interested in Rizal’s works, translating his Mi Ultimo Adios into Bahasa Indonesia, and having it published on his death anniversary. Pramoedya Ananta Toer, the late great Indonesian writer who, in my opinion, warranted the Nobel in literature, to which he had been nominated, knew and admired Rizal’s stance against the tyrannical rule of the Spanish. In his monumental Buru Quartet, the central character Minke is essentially an Indonesian Rizal.

There are memorials to him, all over the Philippine archipelago, whether in the form of statues, plaques, streets and plazas named after him, as well as in various places around the globe. I’ve seen statues of Rizal in Hawai’i and Montreal, plaques in Madrid and Barcelona. He’s even considered a deity in religious sects clustered on the slopes of Mt. Banahaw, viewed by many as a sacred mountain. What’s fascinating about these sects is that they are headed by women, harking back to the tradition of the Babaylan or Katolonan, where the female rather than the male is seen as the natural link to the realm of the spiritual.

What I found out just recently, courtesy of Wikipedia, is that three species were named after him—a testament to his own studies of the natural world, particularly in his years of internal exile in Dapitan: Draco Rizali, a small lizard, known as a flying dragon; Apogania Rizali, a very rare kind of beetle with five horns; and the Rhacophorus Rizali, a peculiar frog species.

Every Juneteenth, the debate over whether or not Rizal the Freemason retracted his views on Catholicism (the Spanish and ultraconservative variety) and returned to the fold heats up. It is a debate I find irrelevant. Rizal was a man of faith irrespective of whether this aligned with the local religious authorities’ interpretations. What is important is the larger context: he died for the country, steadfast in his belief that a nation would arise, liberated from the clutches of a doddering and desperate colonial regime. Copyright L.H. Francia 2021