Matriarch of Fil-Am activist family leaves a lasting legacy

Filipino American community leader Adelina Garciano Domingo passed away at 91. DOMINGO FAMILY

On February 16, beloved Filipino community leader Adelina Garciano Domingo passed away at 91 after a long illness in Seattle, Washington. The Seattle Times obituary described Adelina as the “Mother of Seattle’s Philippine Movement.”

The widow of Nemesio Domingo, Sr., the former president of Local 37 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), Adelina was popularly known as “Ade,” “Auntie Ade,” “Manang Ade,” or “Lola Ade.” She created an indelible legacy of helping build her community, working for social change, and pursuing justice for her son Silme Domingo and his comrade Gene Viernes, who were murdered by Marcos gunmen in 1981.

Ade’s immigrant story

Ade was born in Poro, one of the three Camotes islands in the province of Cebu in the Philippines, during a total eclipse on May 28, 1929. She was the fourth of six children and one of four daughters born to Ines Malagar and Domeciano Garciano, who worked in construction. As she was growing up, everyone in the family would tell her that she took after her paternal grandmother, Mama Itang, who was smart, opinionated, and always busy doing something.

The Second World War broke out when Ade was 12, prompting the family to seek refuge in the mountains, disrupting the children’s education. She learned to grind corn for their food and weave abaca fiber for their clothes. In order to help support the family, she picked and husked coconuts and processed the meat into oil for use in making soap, lighting up lamps, and cooking. The family also sold coconut oil and cassava cakes to augment their income. Ade was full of boundless energy and considered idling away a waste of time, a portent of the kind of hard work and dynamism that would define the rest of her long and productive life.

As the war was ending, the violent clashes began intensifying between the Japanese and American forces as the latter were starting to return to the islands to reclaim the country from the Japanese occupation army. Ade’s family had to evacuate on foot or by boat from barrio to barrio, staying at their friends’ houses. At times they had to sleep in caves at night to evade the desperate Japanese soldiers on the verge of losing the war.

In 1945, the family returned to Poro to resume their lives, and Ade and her siblings went back to school. They moved to a house on a hill, overlooking the town and the sea. Ade loved the new place with its spectacular views and evening breezes, and on warm evenings she would spend hours outside, gazing at the moon and the stars.

The petite and beautiful 16-year old Ade began attracting serious suitors among the newly arrived Filipino soldiers who were assigned to Poro. Determined to go to college, she refused to entertain the idea of getting married early, until she met the tall and handsome Nemesio Domingo, a Filipino-American member of the U.S. Army, who was working in an American military installation in Poro.

Nemesio was born and raised in Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur and came to the U.S. in 1927, on the cusp of the Great Depression, when he was only 18 years old. He was one of thousands of young Filipino men who left the Philippines for work and educational opportunities, and this migration became known as the first wave of Filipino immigration to the U.S.

Ade viewing the memorial wall at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, a Philippine monument to the martyrs and heroes of the anti-dictatorship movement, which includes the names of her son Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes. EDWIN BATONGBACAL

A high school graduate, Nemesio wanted to continue his education but had to work to survive. He got jobs as a migrant worker in California and Washington farms and Alaska canneries. These workers had hard lives, made worse by racism, job discrimination, deplorable working and living situations, and violent attacks by disgruntled white workers who blamed migrants for the unemployment.

After the war broke out in 1941, Nemesio, like many Filipinos who had arrived in the 1920s and 1930s, enlisted in the U.S. Army and was immediately granted U.S. citizenship. Thousands were deployed to the Philippines, and Nemesio was assigned to Poro, Cebu, where he would meet his future wife.

The shy soldier, who was working as a radio man in a building across from Ade’s home, would suddenly show up whenever the young girl arrived each morning to fetch water from a public water pump. Once, Ade saw Nemesio carrying fish he had just bought. She broke the ice by asking him what he had planned to do with them. He said, “Would your mother be willing to cook them for me?” She told him that she might, and thus began his constant visits to her home, under the pretext of bringing ingredients for her mother to prepare.

The night before he left Poro for Manila to report for his next assignment, Nemesio told Ade’s oldest sister Servillana that he would come back to marry Ade.

He wrote to Ade every day, promising to send her to whatever school she wanted to attend. After a courtship that lasted several months, the couple won her parents’ blessings.

War Bride

On a crisp, clear morning on January 24, 1946, the 36-year old Nemesio and 16-year old Ade got married at the old Santo Niño Parish Church in Poro.

Before the new couple settled down in Manila, Nemesio brought Ade to his hometown so she could meet his family. While her husband began his new duties in Manila, Ade stayed for a few months in Santa Maria, where she learned to speak Ilocano so quickly and fluently that people in that town thought she was a native speaker. Besides Ilocano, she also spoke her native Cebuano, Tagalog, and English.

Their eldest child, Nemesio Jr., was born in 1947 in Manila. Two years later, soon after the birth of their daughter Evangeline, nicknamed Vangie, Nemesio Sr. left the country to report to the military base in Minot, North Dakota. Ade, who had started going to nursing school, opted to stay behind with the children so she could continue her studies. Given the choice, she would have stayed in Manila to finish her course but she started getting alarming news that Nemesio had been having medical problems and confined in a hospital.

Ade and Nemesio Domingo, Sr. and their children (from left): Lynn, Silme, Nemesio, Jr., Cindy, and Vangie. DOMINGO FAMILY

In January 1951, Ade left the country with three-year-old Nemesio Jr. and 18-month old Vangie on the SS President Cleveland for the U.S. They arrived in late February in San Francisco, where Nemesio, Sr. picked them up. The reunited family then traveled to Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas, where Nemesio was assigned.

Ade and her children had immigrated to the U.S. under the War Brides Act of 1945. This law granted admission to spouses and minor children of citizen members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

First encounters with racism

Ade had a crash course on racial discrimination when she went to a store in a neighboring city. She was in line to pay when the cashier chose to help the white person behind her. She reported the incident to Nemesio Sr., who explained to her that racism was indeed prevalent in the country and that he himself had experienced unequal treatment in the service. He also shared with her his harrowing experience while employed in a Yakima farm. He and the other laborers would sleep in the cellar of their bunkhouse where it was cooler. One night, a group of vigilantes firebombed the cellar, and they barely escaped with their lives.

One day, Nemesio Jr. came home crying and told his mother that a boy who lived across the street hit him and called him a “Jap.” Ade consoled him by saying that they were ignorant because they had never met Asians before. Before long, she would learn more about how people of color were treated as second-class citizens. She observed that African American soldiers with German wives could not walk hand in hand and were not served in restaurants. They lived in a segregated area within the camp.

Exacerbating Ade’s culture shock was her gnawing homesickness. She wrote to her mother at least three times a week, relating her difficulties in adjusting to a new way of life. Soon, however, the process of acclimatization to a new country took over, alleviating Ade’s frustrations. They got a house outside of the camp, went to church on Sundays, and socialized with other Filipino families. Ade joined a bible class and a choir group.

Ade and Nemesio Sr. had three more children in Killeen – Silme, Cindy and Lynn — making Ade’s schedule even busier. Just as the family had settled into a routine and the older children were adjusting in school, the family had to pack up their things to leave for the new assignment of Nemesio Sr., who had been trained as a medical technician by the Army.

In the summer of 1958, they flew to Munich and took the train to Berchtesgaden, a tiny village in the Bavarian Alps, on the border of Germany and Austria. The family lived in a three-bedroom apartment with a big kitchen and hired a German cleaning lady, easing Ade’s load of household chores. Happily, Nemesio Sr., who was working at the U.S. base clinic, had been enjoying good health, unlike previous periods in the States.

Three years later, as Nemesio Jr. was about to enter high school, his parents had to make a decision that would require the whole family to make another move. Nemesio Sr. did not want his eldest son to stay all week in Munich, where the nearest good school was located, because of news about children doing drugs in that city. He thought that Nemesio Jr. would be better off studying in the States, so he requested a transfer to Fort Lawton in northern Seattle, overlooking the Puget Sound.

At the end of 1961, Nemesio Sr. moved his family to Seattle, Washington, where he would complete his 22 years of service in the U.S. Army, and he and Ade would spend the rest of their lives.

Helping build the Filipino community

Ade and Nemesio Sr. bought a house in Ballard, a neighborhood in the northwestern area of Seattle, which had an incipient Filipino community. The 1960 U.S. Census indicated that there were 4,398 Filipinos in the city, showing an increase, especially among females, compared to the 2,744 recorded in 1950.

The influx of Filipino women after the war, which has been called the second wave of Philippine immigration, changed the character of the Filipino community. Families began settling down in different parts of the country, unlike the previous decades when first wave immigrants were classified as “aliens” and could not obtain citizenship, buy property, nor allowed to marry white women due to the anti-miscegenation laws,

The couple joined regional organizations like the Sons and Daughters of Santa Maria and soon became active in the Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc., which organized social events, such as queen contests and Philippine-themed celebrations, to cohere the fledging Filipino community. Because there was no physical center, they held their dances at the Washington Hall or Chamber of Commerce. FCS later acquired a building and in 1965 opened the new Filipino Community Center on Martin Luther King, Jr. Way, south of downtown Seattle.

Nemesio Sr. joined the Veterans of Foreign Wars with mostly Filipino members, and the American Legion. He also became active in the Caballeros de Dimasalang, a fraternal organization that was founded in the early 1920s, following the arrival of the first wave of Filipino immigrants on the West Coast.

Because the community was still small, Nemesio Sr. and Ade forged lifelong friendships with many FCS members, who became “Aunties” and “Uncles” to their children. Ade and Nemesio Sr. made sure to bring their kids to FCS events in order to connect them with their Filipino heritage.

Vangie, who had worked in recent years at Swedish Medical Hospital, where she was a union organizer and member of the executive board of SEIU 1199, recalls, “As we were growing up, while my parents encouraged us to celebrate and respect other cultures, they consciously took efforts to make us proud of our own.”

While Ade and Nemesio Sr.’s community activism had played a role in inspiring their children to become involved in FCS activities, the young Domingos became much more active politically than their parents had anticipated. Their sons Nemesio Jr. and Silme became leaders in the Asian-American activist movement.

As second-generation Filipino-Americans, their exposure to the civil rights, anti-war, and anti-racist struggles in the late 1960s and early 1970s had schooled them on the power of organizing in advancing the interests of workers and minorities. Nemesio and Silme had worked as cannery workers and seen first-hand the kind of racial discrimination and deplorable working conditions endured by their father and other Filipinos at Alaska canneries. Both were members of the ILWU Local 37and helped form Alaska Cannery Workers Association to enable the cannery workers to have a voice and to file lawsuits to challenge their unjust treatment at their workplaces.

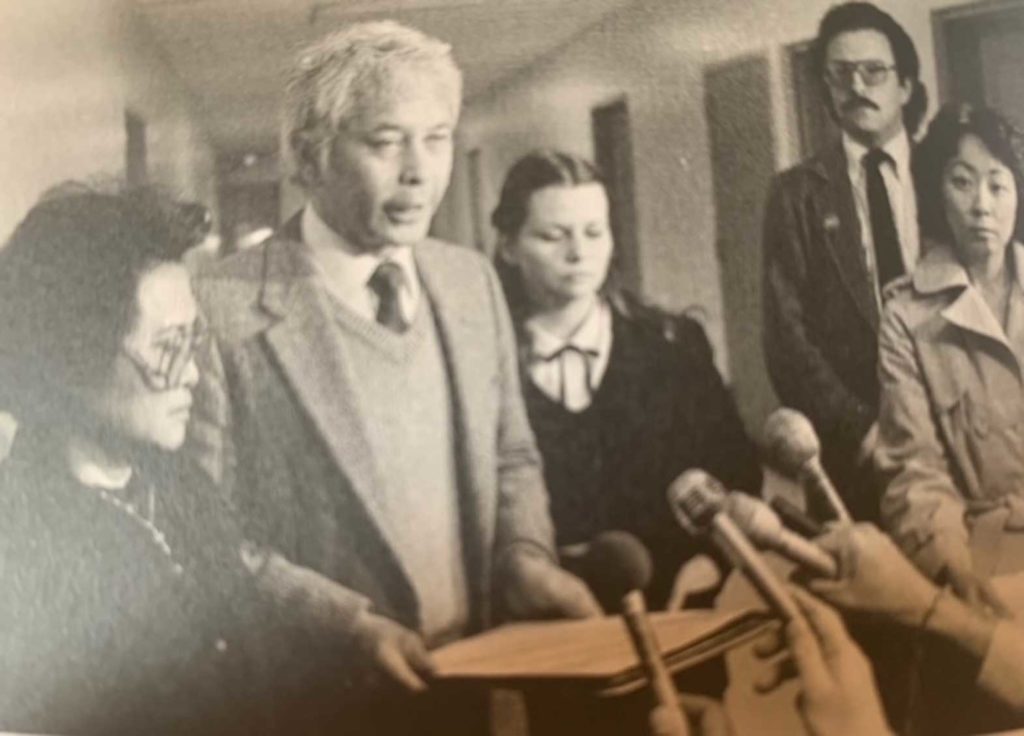

(From left) Ade Domingo, Bob Santos, Terri Mast, Mike Withey, and Elaine Ko, announcing the formation of the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes. ALASKERO FOUNDATION

In 1974, Silme helped found the Seattle Chapter of the Union of Democratic Filipinos or Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP) that opposed the dictatorship in the Philippines and fought for democratic rights of Filipinos in the U.S. Besides Silme, Cindy and Lynn also became members of the KDP. Vangie, a nurse, had volunteered at the Free Health Clinic and supported the anti-Vietnam War movement in the early 1970s.

It was inevitable that conflicts would arise in any family of increasingly diverging views. Nemesio Sr. and Ade became worried about their children’s political involvement and did not tire of reminding them to concentrate on their studies. Once, as Silme and another activist were about to leave her house for a meeting, Ade asked them, “What do you hope to get out of what you’re doing?” Silme gently told his mother, “Someone has to do it, Mom.”

Like most immigrant parents, Nemesio Sr. and Ade believed in providing their children the best education they could afford in order to give them a good future. Nemesio Sr.’s horrific experience of almost getting killed at the Yakima farm made him determined that his children would finish their studies and not suffer from the same humiliations and oppression. He and Ade lived to see their dream fulfilled. All of their five children graduated from college.

Working for social change

As Nemesio Sr. and Ade began to gradually understand and appreciate what their children were trying do to move the community towards a more progressive direction, they supported their activism. But they did not tire of reminding them to be careful as many Filipino Americans were still conservative and deemed any reform efforts controversial. Nevertheless, their place would become a popular gathering place for activists especially during the holidays when Ade and Nemesio Sr. would prepare Filipino-themed feasts for their family, friends, and their children’s comrades.

In September 1972, Marcos declared martial law in order to remain president after the end of his second and final term the following year. Silme and other KDP activists helped build coalitions to lead the anti-dictatorship movement in the city. They also joined with other progressive members of the FCS to form the Filipinos for Action and Reform (FAR) to help transform the FCS from a primarily social organization into a more relevant institution responsive to the needs of Filipino Americans.

In 1979, FAR ran a slate for the FCS election with Vincent Lawsin for President, Ade for First Vice President, and some KDP activists for Board members. Della, a KDP leader who had worked closely with Ade on the FCS reform work, recalls, “She worked so hard during the campaign and was key in mobilizing the more progressive leaders to support FAR’s platform, which pushed for programs to provide services for the growing community. FAR also wanted the Center to be a place for free exchange of ideas about discrimination in the U.S. and developments in the Philippines.”

The FAR slate won the election, and Ade took on fundraising because she knew the importance of funding to enable FCS to start providing social services. She was well equipped for this task as she had financial experience working at banks, first at People’s National Bank and later at Seattle First. Though Ade never got a college degree, she excelled at her jobs that she kept getting promoted.

As members of FAR began to institute reforms at the FCS, the Communist labeling swiftly began. The conservatives from the Consulate to pro-Marcos members of the FCS joined forces in attacking KDP activists and FAR members. Ade remembered Local 37 president Tony Baruso calling her children, “Mao, Mao,” referring to China’s Communist leader Mao-Tse-Tung.

Della says, “FCS members, including some of her longtime friends who did not support reforms, turned their backs on Ade and started calling her names. They accused the family of being ‘Communists’ and used the warning ‘Beware of the red hand’ in their propaganda’. Some even went as far as dissuading funders from giving money to FCS.” The vicious attacks on FAR and the increasing polarization in the community on the Marcos dictatorship helped defeat the FAR slate in favor of the conservatives in the next election.

In 1980, Silme ran as Secretary-Treasurer and Gene as Dispatcher as part of Rank and File Committee’s slate in the Local 37 election. The RFC had assessed that it was not the right time to challenge the still popular incumbent Baruso, a conservative, a friend and supporter of Marcos, and considered an integral part of the corrupt system at Local 37. However, it was common knowledge that it would be a matter of time before Silme would run for the top position.

Baruso was re-elected as president and Nemesio Sr. as a vice-president. Silme, Gene, and several RFC candidates also won, giving them the majority on the Board. They did not lose time in instituting new policies to eliminate corrupt practices in hiring. The anti-reform elements in the union, including members of a local gang called Tulisan, did not take these radical changes lightly. They had been coddled for years by corrupt Local 37 officials, who had benefited financially not only from unfair dispatching of workers but also from gambling at the canneries handled by the gang members.

Silme and Gene, who occupied key Local 37 positions, started getting anonymous threats of physical violence. These intensified in the spring of 1981 after the ILWU Convention in Oahu, Hawaii. The union leaders had proposed a resolution, mandating ILWU to send a delegation to the Philippines to look into the rights, working conditions, and union organizing of Filipino workers. After difficult debates and negotiations, as well as maneuverings by the pro-Marcos forces, the resolution passed. Gene’s first-person account of his maiden trip to his father’s homeland the previous month added gravitas to the proposal.

Barely a month after the Hawaii conference, a heartbreaking tragedy would strike Seattle that would have repercussions nationwide and internationally for years to come.

Pursuing justice for Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes

On Monday, June 1, 1981, Ade was working late at the bank when comrades of Silme suddenly came and gave her the grim news that Silme and Gene had been shot at the Local 37 union hall. Gene was immediately killed, and Silme was brought to Harborview Hospital. As the activists were driving her to the hospital, Ade remained in disbelief about she had just heard. Silme had given her a ride that morning and before she got off the car he had asked her, “Can I have some money, Mom, I don’t have any cash.” Ade gave him her last twenty dollars in her pocket.

Silme underwent several surgeries but he died the following day. While in the ambulance and hospital, he bravely struggled to name and describe Jimmie Ramil and Ben Guloy, members of the Tulisan gang, as their assailants. Gene, 29 and single, was survived by his family in Yakima, Washington. Silme, also 29, left behind his family, longtime partner Terri Mast, and their daughters Ligaya and Kalayaan, aged three and one. The progressive movement in Seattle and nationwide joined the families in mourning the two young activists who tragically lost their lives fighting for the rights of workers in the U.S. and human rights of Filipinos in the Philippines.

Ade had a hard time accepting the loss of Silme but struggled to stay strong because Nemesio Sr., who was close to Silme and grieving his death deeply, had a heart condition. Nemesio Jr. and Cindy became the spokespersons for the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes. Days after the murders, unbowed by the violent attack on the union, Mast, Della, Lynn Domingo, and other RFC members immediately carried on with the reform work at Local 37, picking up where Silme and Gene had left off.

Local 37 president Baruso was named a suspect after the police found the semi-automatic gun that was used to execute the two activists was registered in his name. For baffling reasons, he was not indicted in the case. Nemesio Sr. was devastated as he and Baruso were longtime friends and both belonged to the Caballeros de Dimasalang. The role of dictator Marcos was also put under scrutiny because Silme and Gene were not only union leaders but also prominent anti-Marcos activists.

Silme’s death left Ade heartbroken and she stopped being active at FCS. To add to her grief, some FCS members did not show sympathy towards their family and started shunning the Domingos, incredulous that Baruso and Marcos could be involved in the murders despite the mounting evidence to their possible involvement.

A Seattle court found the two gunmen, Ramil and Guloy, and Tony Dictado, the leader of the Tulisan Gang, guilty of the murders and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. After the verdict, Ade sought the mothers of Ramil and Guloy. She said, “I wanted to hug them and tell them that I was sorry that they were losing their sons just as I had lost my son. I wanted to pray with them but sadly they did not want to have anything to do with me.”

The families of the murdered men had requested the prosecutor not to ask for the death penalty because they believed that the unjust justice system in the U.S. disproportionately applied the death penalty to people of color.

A year later, Baruso was running for re-election as president of Local 37 when he was found guilty of gross violation of election rules and blatant cheating. He was ousted from his position, and Nemesio Sr. took over as president. In the next election, Mast ran as president and RFC members for the Executive Board positions and won, showing the advances in their union work.

After the successful criminal trials, the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes began the next challenging phase of its work. The families filed a civil suit to unravel the powerful forces behind the murder conspiracy and make them accountable for the murders. Cindy, who had moved back to Seattle from Oakland right after the murders, would lead this work.

Though still grieving over Silme’s death and gravely hurt from the treatment her family had received from the conservative wing of the Filipino community, Ade remained determined to help the CJDV in its quest for justice for her son and Gene.

Della, who has served as a Seattle City Council member in the early 2000s, says, “Ade could have stayed bitter and inactive but she became even stronger after what she had gone through. She participated in the CJDV work, which fueled her awareness in justice and broader issues, while at the same time taking care of her family. She kept moving forward to work for a better community.”

Emma Catague, a friend of the Domingo family for decades who had worked with Ade at FCS, says she learned a lot from Ade. She recalls, “Ade was a strong leader fiercely committed to working for the community while remaining devoted to her family. She was fearless and spoke her mind, which encouraged younger women like myself to aspire to be like her. I would always remind myself, ‘If Ade could do it, so could I.’”

Catague, who is now the Program Supervisor at the Filipino Community Center and also involved in the movements against gender-based violence and police misconduct, says she was impressed by Ade’s conciliatory approach towards people who did not share her views. “She would seek them out to try to find a common ground.” Catague adds, “After Ade stopped being active in FCS, she continued being concerned about the community and showed her support by attending events and giving donations to the Center.”

During the trial for the civil suit, Ade’s determination to pursue justice extended into the courtroom. Mike Withey, a longtime public interest and human rights attorney who had served as CJDV lead counsel in the case, states, “Ade was an incredibly generous person, very sharp, and had a passion for learning. A strategic and tough-minded leader that no one could push around, she was the emotional center in the CJDV.”

On December 15, 1989, after years of CJDV legal work, community organizing, and coordination with the prosecution, a jury found the Marcoses guilty of the assassinations of Silme and Gene. The trial and verdict made history. It was the first time a former head of a foreign government was put on trial for the murders of U.S. citizens and found guilty and liable for the crimes. The details of this case may be found in the book of CJDV lead attorney Withey, Summary Execution: The Seattle Assassinations of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes.

Withey calls Ade’s testimony one of the highlights of the trial. “She was able to paint a detailed picture of Silme and what a great father he was to his two daughters. I believe that her ability to speak truth to power convinced the jurors to give a bigger settlement to the families of Silme and Gene than what we had asked for.”

Barely two years after the victory in the civil suit, Baruso was finally brought to trial and found guilty of being part of the conspiracy to kill Silme and Gene. Like the Tulisan members, he was also sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. (In 2008, Baruso died of natural causes in prison.)

Life after CJDV

In 1991, Ade suffered another painful loss when Nemesio Sr., her husband of almost five decades, passed away. She visited Nemesio and and Silme’s graves every week and maintained the tradition of hosting family dinners on Sundays. She devoted hours tending to her flowering garden, which was much admired in the neighborhood. She enjoyed the visits of her grandchildren, and later great grandchildren, who gravitated towards her home to enjoy being pampered by their Lola Ade’s hugs, cooking, and unconditional love. After retiring from the bank, Ade opened her home for two decades to host foreign students, who called her the affectionate “Lola Ade.”

In 2011, Ade, together with members of her family, Gene’s family, and KDP activists, went to the Philippines for an emotional visit. They attended a ceremony on November 30, commemorating Silme, Gene, and other heroes in the fight against the Marcos dictatorship. Their names were inscribed on the memorial wall at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, a monument to the martyrs and heroes of the anti-dictatorship movement, located in Quezon City. It was a moving moment for Ade and everyone in the group as Silme and Gene, the first Filipino Americans to be honored at Bantayog, were finally acknowledged for their martyrdom on Philippine soil.

The Domingo family with their matriarch Ade (seated front row, second from right) in Poro, Cebu for a family reunion. DOMINGO FAMILY

At 85 years old, Ade had a knee replacement surgery, forcing her to cut back on her activities. She had to deal with chronic pain from arthritis and other ailments and finally stopped cooking after she turned 88. Yet, she still managed to make three more trips to the Philippines with her family, including her great grandchildren. She always stayed in her childhood home that she had remodeled over the years, surrounded by members of her Poro kin, who doted on her. In one nostalgic moment during her interview with this writer, Ade said, “I would like to go home and live the rest of my life there, but I will greatly miss the kids.”

On February 16, Ade died peacefully in her sleep. Cindy, who had been caring for Ade, together with her sisters Vangie and Lynn, remarks, “My Mom taught her family here and in the Philippines so much about love, giving, and living. Her heart and home were always also open to her family, friends, the activists, and her community.”

Cindy, who had retired as Chief of Staff to King County Councilmember Larry Gossett in 2019 and continues to be active on women’s and workers’ rights, racial justice, and international solidarity with developing countries, states, “My mother was a woman ahead of her time – outspoken, progressive, confident, and a fighter. She faced the many challenges in her life with so much courage, and we will forever be inspired by her meaningful legacy.”