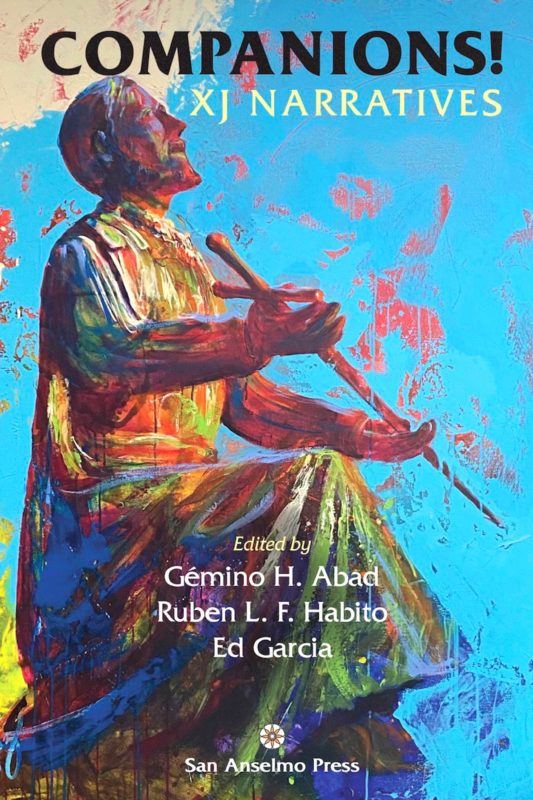

“San Ignacio, Kawal ni Kristo” by Celeste Lecaroz

NEW YORK—On May 20, 1521 a 31-year-old Basque nobleman by the name of Íñigo López de Loyola, fighting for Pamplona against the French, had his right leg shattered by a cannonball. Up until that point, Íñigo was the epitome of the worldly, swaggering warrior, a womanizer and a peacock ready to draw his sword when he felt he was being insulted. But during his period of convalescence he read up on the lives of Jesus and the saints, undergoing a spiritual conversion, a metamorphosis, exchanging his bodily armor for one more spiritual, in service this time not to earthly royalty but to the Son of God.

That soldier came to be known as Ignatius of Loyola, the soldier-saint whose spiritual epiphany led him to found the Society of Jesus, in 1539 in Paris, with Peter Faber and Francis Xavier. In 1540, Pope Paul III gave the order the seal of his approval. Fittingly, Ignatius was the Jesuits’ first Superior General.

This year 2021 thus marks the quincentennial of Ignatius’s journey to Damascus—from cannon fire to canonization, at the same time that 2021 also marks the quincentennial of Ferdinand Magellan’s consequential and tragic landfall in the Visayas.

The first Jesuits assigned to Las Islas Filipinas arrived in 1581, from the Province of Mexico—15 years after Imperial Spain’s takeover of the archipelago. A decade later, in 1591, they established missions in Batangas and Rizal provinces. But in 1768 the Jesuits were expelled from the Philippines by royal decree—as they were from other Spanish colonies the year prior—due to the widespread perception that they were too close to the papacy and too involved in local politics. Allowed to return in 1859, the Jesuits founded Ateneo de Manila in December of that same year.

Coinciding with the start of the yearlong celebration of the Ignatian Year, to last until the Feast of Saint Ignatius in 2022, is the publication of Companions: XJ Narratives (San Anselmo Press, www.sananselmopress.net), a compilation of biographical essays by ex-Jesuits, hence “XJ.” Edited by Gemino Abad, Ed Garcia, and Ruben Habito, all XJs, the book is divided into two parts, the first half made up of essays written by those still of this life, and the second half, mainly of remembrances of those departed XJs by friends or family members. My essay on my late older brother Joseph, an XJ, is included, as are brief essays on him by my sister Judy, and one of his sons, Amos.

While he was alive my brother and other XJs would gather every second Friday of each month, to share a meal, renew friendships, and discuss ideas and individual undertakings. It seems that the plans for putting forth this book were finalized after one such get-together in late October 2019, when some of the XJs came by to my brother’s wake to, as Ed Garcia puts it in his “Introduction,” “bid farewell to a dear friend and companion, Joseph Francia, who had suddenly passed. Joseph was an economist who throughout his life was engaged in the struggle for social justice to improve the lot of farmers and workers, and was recently involved in identifying servant leaders to support in local and national electoral exercises. It was then that we firmed up the idea of contributing our stories to a manuscript that we could own and share with others.”

As every Jesuit educated person knows, underlying the order’s Ratio Studiorum, or Plan of Study, is the principle of dedicating oneself completely in whatever endeavor he or she is engaged in, in the magis manner, or Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, “for the greater glory of God”—assuming of course that what is being undertaken is for the good. At Ateneo de Manila High School we were instructed to write the abbreviation AMDG at the top of every test paper handed in. And I remember all too well, the term JUG, or Judgment Under God, a form of punishment, often corporal, our mentors meted out for infractions. (I sometimes wonder if Jose Rizal, Ateneo de Manila’s most famous alumnus and who would have become a Jesuit were it not for 1872 and the barbaric execution of three Filipino secular priests, ever had to do JUG.)

Taking off the habit, or cassock, and leaving the Society doesn’t mean the Society leaving that person—or that the habits ingrained in them by the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises and being a man for others would wither away. With a variety of styles that makes this collection refreshingly diverse and readable, Companions: XJ Narratives makes abundantly clear that whatever journey each one of these XJs has embarked on, and however different each may be from the other, the Ignatian spirit unites them, rendering them a company of brothers, sharers and partakers of the same bread. Copyright L.H. Francia 2021