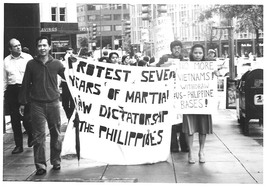

Members of the Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship protesting in Washington, DC, against US support for Marcos.

NEW YORK—While the United States was aggressively intervening in Vietnam’s destiny, on the domestic front, the antiwar movement was gaining steam, and New York certainly saw a lot of antiwar demonstrations. It was through the antiwar movement that I came to know of the 1899 Philippine-American War, and how the tactics used in Vietnam were in many ways a repetition of U.S. strategy in the Philippines.

One of the architects of counterinsurgency policy in Vietnam was Col. Edward Lansdale of the CIA, an adviser to Ramon Magsaysay, the Defense Secretary, later on president, who succeeded in putting down the Huk insurgency of the 1950s. Supposedly the model for the fictional Colonel Hillandale in Eugene Burdick and William Lederer’s novel, The Ugly American, Lansdale introduced the so-called strategy of winning hearts and minds that had worked in Central Luzon but failed miserably in Vietnam.

Bowing to American pressure, in 1966, Marcos sent a contingent of combat engineers to Vietnam. It was clear to me, as it was clear much earlier on to activists back home, that this was an instance of little brown brother doing what white elder brother wanted. It was inconceivable that martial law would not have had Washington’s approval.

Reaction in New York to Proclamation 1081 decreeing a state of emergency in the Philippines was mixed. There were those who applauded strongman rule (as there are those who today applaud Duterte’s iron-fisted rule), believing that authoritarianism was the answer to the many systemic problems bedeviling the country. There were those who didn’t want to get involved; the Philippines represented the past that they had no wish to revisit. And there were those opposed to Marcos and his regime, but from differing political perspectives.

I got involved in the opposition through a monthly magazine whose publisher was Loida Nicolas Lewis. At that time, she and her husband, Reginald, now deceased, were not yet multimillionaires but earned enough from their lawyering to finance its publication. The magazine would be the continuation of Imelda’s Monthly, a Manila-based satirical broadsheet began by Imelda Nicolas, Loida’s younger sister. The monthly was not happy reading for Imelda Marcos and her coterie.

Imelda’s Monthly came out twice before Proclamation 1081, and in the immediate aftermath, all copies were seized and the publisher’s home raided. Loida decided to resurrect it in New York, now renamed Ningas Cogon, or Brushfire, a term that could also refer to something fleeting, for none of us were sure how long the monthly would last.

Some other contributors were Nelson Navarro who was its editor for a while, Angie Cruz, Lolita Lacson, Rene Navarro, and the late satirist Nonoy Marcelo—the brilliant creator of Tisoy and Ikabod, comic-strip characters through whose lives Nonoy offered pointed critiques of Manila society.

The enemy was the Philippine Consulate, by then housed in the Philippine Center on Fifth Avenue in midtown, just four blocks south of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The center was the dark tower of Mordor, the only building on Fifth Avenue, it is said, to have no windows—symbolizing perfectly the regime’s fear of light and of transparency. We boycotted it, and protested on the sidewalks whenever a high-ranking regime official was in town.

The consulate pressured Filipino stores and restaurants not to sell or display copies of Ningas. It blacklisted the staffers, but as most of us used aliases, the list had no effect. The consulate was friendlier towards The Filipino Reporter, a weekly established a couple of months before martial law was declared, but thereafter metamorphosed into a pro-Marcos paper. Out of San Francisco came the more established Philippine News, also a weekly and solidly anti-Marcos.

The list of anti-martial-law groups, spread across the U.S. but based mainly in urban areas, was long and of varying ideological stripes. Among these were Katipunan ng Demokratikong Pilipino; National Committee to Restore Civil Liberties in the Philippines; Movement for a Free Philippines; Friends of the Filipino People; Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship; Ninoy Aquino Movement; and International Association of Filipino Patriots.

And then there were the “steak commandos,” so-called because they plotted against the regime over expensive steak dinners. Not that having a steak meant you couldn’t be serious, but the appellation targeted trapos (a Filipino word for “rags” and also shorthand for “traditional politicians”) whose braggadocio was mostly self-serving. They resented being excluded from the trough that Marcos and his cronies were feeding off.

We’d hear routinely of rape, torture, of desaparecidos, back home, or in Manila parlance, “salvagings.” We never imagined that the dark side would manifest itself across the Pacific, but manifest itself it did, in the murders of Gene Viernes and Silme Domingo, young union organizers in Seattle who campaigned vigorously against martial law, and the disappearance of Primitivo Mijares, once part of Marcos’s inner circle, who had defected in 1975 and subsequently wrote Conjugal Dictatorship (recently reprinted), an exposé of the corrupt ways of Ferdinand and Imelda. One day Mijares simply dropped out of sight. Later on it was bruited about that he had been enticed back to the fold, but once he was in the hands of the regime, had been flown in a helicopter over the ocean and then made to join the fishes—literally dropped out of sight.

But the salvaging that signaled the end of the Marcos regime was the assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino Jr. in 1983, when he returned after three years of living in exile in Boston. Escorted off the plane at the airport in Manila (now known as Ninoy Aquino International Airport) by a military detail, Ninoy was quickly gunned down. Two million people lined the route of his funeral procession—which the Marcos-controlled media basically ignored.

By then I was working as a part-time copy editor at the weekly The Village Voice. An editor asked me if I wanted to write about Aquino’s murder. I did, and an issue or two later, the first part of what was to become a three-part poem, “Three Voices for a Fallen Man,” came out. I had also introduced the editors to the fictionist Ninotchka Rosca. Alongside my poem was a feature by her, on the politics that lay behind the killing.

In February of 1986, in what came to be known as the bloodless People Power Revolution (misleadingly, in my view), the Marcoses were forced to flee to the balmy air of Hawaii. By then Ningas had ceased to exist, had stopped printing in 1979. I forget now why, but that it had lasted for seven years was astounding.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2017