‘Hiya’ hinders accurate study of Filipino immigration in US

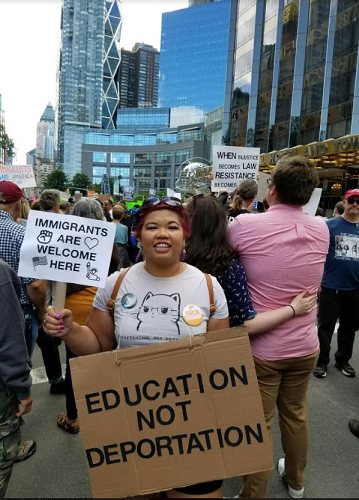

The author, Daniela Mila, protesting the repeal of DACA in front of Trump Tower, September 9, 2017. THE FILAM

“I’m getting my PhD in sociology.”

“Wow, ang galing naman!” (Wow, that’s so impressive!)

Whenever Filipinos ask me what I do for a living, I explain that I am a Ph.D. student in sociology. As a Filipina who purposely pursued a career in a non-medical field, I am a unicorn in the Filipino community. I selected my career not because I want to be financially secure—the ultimate goal of any child of Filipino immigrants—but because our community faces deep issues with the current US immigration policy.

And yet, the Filipino community is not talking about these issues. At least not out in the open. If you are lucky enough to be in a party with a house full of Filipinos, then your chances of hearing immigration stories are relatively high.

“Pupunta na dito yung kapatid ko! Ten years kaming hindi nagkita.” (My sibling is finally coming [to the US]! I haven’t her in 10 years!)

“Hanggang ngayon, hindi pa siya citizen. Nag-age out kasi sa petition, eh.” (Until now, she’s not a [U.S.] citizen. She aged out of the petition.)

Separations and problems

These narratives of family separation and problems with legal status are commonplace within the Filipino community both in New York City and around the country. For Filipino immigrant families, family separation—sometimes spanning years, sometimes decades—has evolved into the norm rather than the exception.

The discussions surrounding these issues in Filipino parties are typically descriptive and not critical of the institutions at work.

The attitude of “Bahala na” (leave it to chance) or as it is colloquially known, Bahala na si Batman, also speaks to the religious faith of Filipinos: the universe will help you solve your problems and there is no need to raise a ruckus.

I, however, cannot remain silent about these issues.

I am conducting my dissertation on how legal status affects ethnic identity formation in Filipino immigrant young adults. I interview US citizens, permanent residents, non-immigrant visa holders and undocumented Filipinos living in the Greater New York-New Jersey metropolitan area who are between 21 and 32 years old.

After about two years of data collection, I have collected 36 interviews—20 U.S. citizens, eight permanent residents, seven non-immigrant visa holders, and one undocumented person. My goal is to conduct interviews with 15 Filipinos for each legal status group.

Difficulty finding interviewees

When I wrote my dissertation proposal, I surmised that the Greater New York-New Jersey metropolitan area’s large concentration of Filipinos would make my data collection progress smooth. I interviewed 20 Filipino U.S. citizens without much of a hitch. About 5 percent of the 3.4 million Filipinos in the United States reside in New York State while New Jersey has another 5 percent.

Despite this large concentration of Filipinos in my recruitment sites, I have found it extremely difficult to find noncitizen Filipinos to interview. The “hiya” (shame, embarrassment) associated with legal status, especially with TNT’s (‘tago nang tago,’ literally translates to “hiding and hiding”), has made it impossible for me to find willing noncitizens for my research.

Even Filipinos with legal status are afraid to be interviewed, for fear of accidentally revealing too much. I found this resistance to be surprising; in social settings, Filipinos are more than happy to “out” their family or friends’ legal status. But when I ask for help and referrals from potential participants, I am often met with hesitation and sometimes downright hostility.

Inadequacies of system

As a researcher, I am obligated to show how the inadequacies of the current immigration system affect the Filipino and Filipino American community. The current literature on Filipino immigrants does not reflect the reality of Filipino-U.S. immigration. At the time of this writing, there are few studies on Filipino immigrant young adults living in the United States. Present studies on Filipino immigrants focus on those with U.S. citizenship. Conclusions based on these may not apply to all of the thousands of Filipinos who immigrate to the U. every year. Finally, the narratives of Filipinos who immigrate, become undocumented and live their lives in the shadows, are sorely lacking in the current academic literature and political discussion.

The Department of Homeland Security estimates 310,000 out of the 3.4 million Filipinos residing in the United States are undocumented. Of those, approximately 22,000 young Filipino immigrants were eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Now that President Trump is putting an end to the DACA program, the 6,000 Filipino young adults who applied for DACA are at risk of deportation.

Now more than ever, the Filipino community needs research that discusses the implications of the U.S. immigration system and pushes the dire need for comprehensive immigration reform.

Daniela Pila is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University at Albany, SUNY. She would very much like to conduct more interviews with noncitizen Filipinos and finish her dissertation sometime before the next millennia. She can be reached at dpila@albany.edu. She lives in Rockland County with her husband and their fur child, Luna. To learn more about Daniela’s research, please click on the link below: https://youtu.be/13abPYdw5bQ.