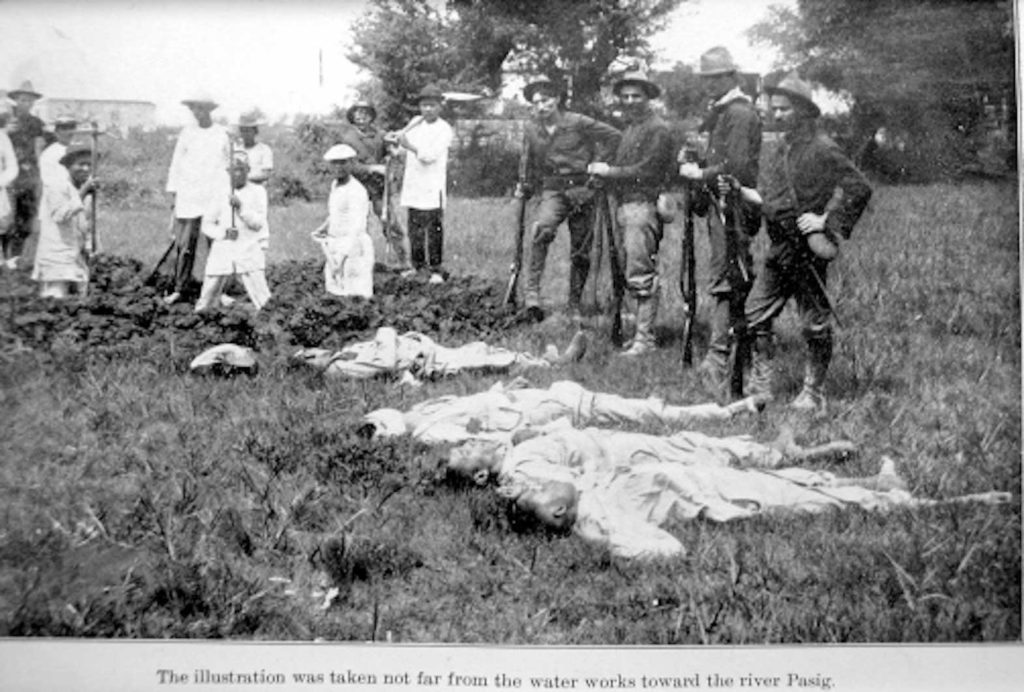

U.S. troops posing before dead Filipino “insurrectos.”

NEW YORK—This past February 4th marked the 122nd anniversary of the 1899 Philippine-American War, one that continues to be invisible to the vast majority of Americans. If it is known at all, it would be as the “Philippine Insurrection.”

Words matter, labels matter. Webster’s defines insurrection as “an act or instance of revolting against civil authority or an established government.” By branding the refusal of a country, in this case the Philippines, to accept and even welcome the United States as its new colonial master, as an “insurrection” is to downplay its revolutionary significance and marginalize it as a wayward attempt to overthrow a legitimate government.

In fact, it was the other way around: the so-called “insurrection” was the First Philippine Republic’s recourse to armed conflict in order to oust a foreign invader that proclaimed itself the archipelago’s government, promising to introduce democracy to its inhabitants by decidedly undemocratic means. There would be a government but it would not be one of the people, by the people, and for the people. It was imperialism, American-style.

What does an insurrection look like? Well, the world saw a textbook example last January 6th, when a crowd—no, a mob—of white supremacists, Neo-Nazis, QAnon cult followers, Oath Keepers, Three Percenters, assorted simpletons, and empty-headed devotees of a false idol by the name of Donald J. Trump and egged on by his incendiary rhetoric, stormed the Capitol in a violent attempt to disrupt and prevent the certification by Congress of the Biden-Harris decisive win and thus keep Trump in power. Members of Congress had to hide to avoid being potential targets of a mob baying for blood. Clearly illegal, clearly an insurrection, for which the former president has deservedly been impeached for the second time—a historic first.

In contrast, the presence of US troops in the archipelago in 1899 was so evidently illegal and immoral—the complete opposite of how it was and continues to be represented in textbooks, proving the adage that history is written by the victors. It is of a piece with narratives dealing with the darker aspects of this country’s history, from slavery to genocidal wars against Native American nations, from the internment of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans during World War II to the innumerable, unjustified wars including those on Vietnam and Iraq.

Officially the war is presented as having lasted for just three years, from 1899 to 1902. In actuality, it continued for well over a decade, ending only in 1913. Over the course of the war, a total of 125,000 US troops were in the islands, with a little more than 4,000 deaths. The death toll for the Philippines was much higher: at least 250,000 to a million lives lost. In contrast, the 1898 Spanish-American War (really the opening act to the 1899 conflict), lasted barely four months and resulted in about 40 US deaths.

And yet it is this war that is remembered, valorized, wherein the United States as avenging angel was out to vanquish an oppressive colonial power and liberate the Philippines—and Cuba and Puerto Rico. In 1900, veterans of the campaign in the Philippines formed the Military Order of the Carabao. Initially meant as a humorous counterpart to the Military Order of the Dragon—founded by US officers who had, along with other foreign troops, put down the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China—the Carabao Order survives, but not the Dragon Order.

According to Wikipedia, “The organization sponsors an annual social event called the Carabao Wallow, a black-tie, military-dress affair attended by members of the U.S. military, the US government, and corporations associated with the military, such as defense contractors. Members perform semi-professional musical skits at the Wallow that often poke fun at national and international issues as well as current events. It is not uncommon for the Carabao players to spoof the high-ranking guests seated at the Head Table.”

At their gatherings, the Carabaos sing “the Soldier’s Song,” considered their anthem, one originally sung by US troops facing the revolutionary forces of General Emilio Aguinaldo.

In the days of dopey dreams—happy, peaceful Philippines,

When the bolomen were busy all night long.

When ladrones would steal and lie, and Americanos die,

Then you heard the soldiers sing this evening song:

Damn, damn, damn the insurrectos!

Cross-eyed kakiac ladrones!

Underneath the starry flag, civilize ’em with a Krag

And return us to our own beloved homes.

The fact that in the twenty-first century, these racist lyrics still have currency among influential members of the military/industrial complex is deplorable. If statues that glorify shameful episodes in this country’s history can be torn down, why not treat this organization in the same manner? Isn’t it time these carabaos were put out to pasture? Copyright L.H. Francia 2021