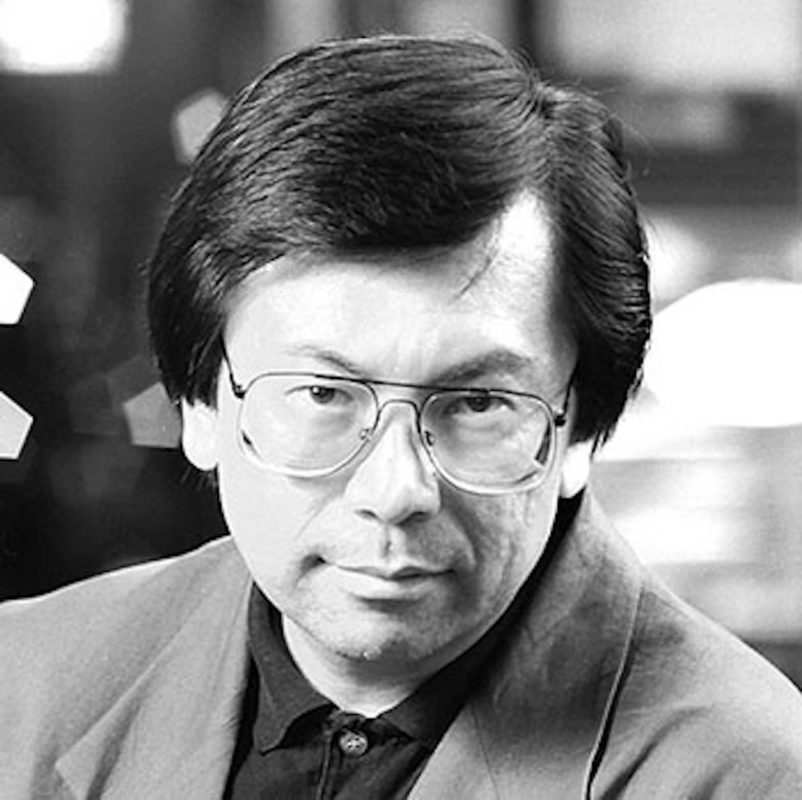

Coronavirus has taken photojournalist Corky Lee’s life.

It’s been just about a year since the first U.S. Covid death (Feb. 6, 2020, Santa Clara, California). The death toll is now over 441,257 people and counting–an obscene number that continues to rival the senselessness of wars. And that number doesn’t include the tens of thousands of people who were somehow involved in their lives.

The grievers, the mourners. We are plenty. Reflective.

If there are still people who think the pandemic is a hoax and refuse to mask up, I refute them immediately by summoning the last image I have in my mind of Corky Lee. Everyone’s writing about him now in the mainstream media because Corky was a photographic avenger.

That’s how I think of my old pal, the Asian American photographer, and the injustice of his life ending to Covid. I saw him a week ago. He was gowned up in a hospital bed, intubated, without hope.

And the sad thing is Corky knew how significant this was from the very beginning. He was out there making sure people knew about the impact of the pandemic on Asian Americans, particularly Filipino American nurses, who were disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus.

The National Nurses United tally last fall put the Filipino nurses who died from Covid at one-third of all nurses who’ve died. Filipinos make up only four percent of all nurses.

It’s the racism of disproportion, the story of a pandemic that expands inequities. As a 73-year-old-Asian American, Corky had to feel that injustice as he battled for his own life.

I know he did.

We were both fighters for the inclusion of our Asian American stories, using whatever media talents we had, both of us extremely sensitive to society’s slights and omissions.

The last few days since his death last Wednesday, I’ve been going over my Corky files. There are several passages in a podcast interview I did with him in 2017 that captures what I mean when I say Corky had a unique sensitivity, an intolerance for injustice. It guided his life.

The most emotional moment was when he recalled an OCA event in 1969 at the 100th anniversary of the Golden Spike in Utah. More than 400 people were there, including Phillip Choy, the preeminent Chinese American historian and architect, one of the first professors of Chinese American History. He was supposed to speak. For some reason, he was snubbed.

Why? Corky never said. But maybe it was because Choy was a historian who was never afraid to create our space and claim our history as something that mattered. Choy was never afraid to speak critically, truthfully.

Corky never forgot that. In 2002, at the 133rd anniversary, Choy once again was scheduled to speak and nearly shunned again. “I just led this chant, ‘Let him speak, let him speak,’” Corky said. Students in the audience picked up the chant, and Choy finally did speak.

Corky remembered seeing Choy later. “You are the reason I organized this flash mob [photo],” Corky told him. It was an homage to Choy for what Corky learned from him about history, truth, and photography. Then Cory told Choy what he had witnessed at the 100th anniversary. “I know what happened to you.”

Corky started to choke up at the memory on the podcast. At the time of the recording in 2017, Choy had just died two months earlier, at age 90 from cancer. On our phone call, you can hear Corky hold back tears. (It comes around 1:27:49 after he comments on the questions I asked Connie Chung at a journalists’ convention in Los Angeles.)

For Corky, photography was evidentiary. It made us whole with the truth.

His best photographs And then there’s the part of the podcast where Corky talks about what he considered his top five photographs ever. Of course, he mentions the Transcontinental Railroad photograph where he puts in Chinese left out of the Golden Spike photograph.

But he also talks about his photograph of a Sikh man in a red turban that won a New York state journalism award. The photo was taken four days after September 11 in New York City’s Central Park during a time people were targeting turban-wearing South Asians as terrorists.

When Corky got the award, he saw a judge’s comment about the man having a “compelling devious stare.” “What constitutes a devious stare?” Corky said to me in the podcast. “Those three words just kind of rattle my cage.” He meant it.

“At some point before I’m six feet under pushing up daisies, I’d like to meet the person who wrote that.” That’s the kind of guy Corky was. He knew injustice. He could sense it. He could feel it. He could see it.

The podcast—“Emil Amoks Takeout” The one thing about listening to a podcast is that it can reach a level of pure human spirit. Hearing a passionate disembodied voice tends to do that. And then the sound alone goes to the best image you’ve got of the speaker that’s in your head.

I’ve remixed the sound on a new podcast special on my Emil Amok’s Takeout, starting with a reading of my farewell to Corky, so you can hear the notes that were in my head when I wrote it. (:00-9:54). And then I added a whole interview I did with Corky at the beginning of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, May of 2017. (It starts at 10:03).

When I talked to him, Corky was preparing for his May 10 trip to Utah for another Golden Spike flash mob photo. It was always his way of putting the Chinese back into Chinese American history. As I listened to the podcast again I realized we were simply having the conversation that had always eluded us. I’d known him for more than 30 years and we never sat down and chatted with each other for more than an hour. Ever.

Not unless it involved food, when we would engage in between bites at Nom Wah Tea Parlor in New York’s Chinatown. And then the food was more the main course.

Or unless it was at an event, where we grabbed conversation in between shots and quotes. I’m glad I pushed the record button for this when all we could do was talk to each other about his photography and his life.

I wanted to know the Corky secret. What was he looking for through the lens, and what made him press the shutter? He said if a volume of his photographs were put in some library 50 years from now, ”The important thing is that people see what life was like in my time period.”

He said young people come up to him and say they’ve seen his photos in Asian American courses, but can’t recall a single shot. “I think they resonate with the name Corky Lee, “ he told me. “How many Corky Lees are out there?” There was only one, who seemed to be everywhere. But he was selective too.

“I’m looking for something that somebody else probably has not examined closely,” he said. “It’s kind of like the “Star Trek” mantra. You know, I just go where people don’t go.”

Listen to my podcast to hear our conversation.

Podcast guide (Subjects as they appear in podcast).

–Emil reads his farewell.

–Intro to interview with Corky.

–On photography and what makes him different.

–Learning the history of the Transcontinental Railroad in grade school.

–Going to Queens College

–Comparing our fathers’ Filipino and Chinese immigration stories.

–His father’s story.

–His father as a Sergeant in the Chinese American Unit assigned to the Flying Tigers in WWII.

–Learning photography from his dad and how the No.1 son almost didn’t take up photography for fear of his father’s verbal abuse.

–Corky’s first job as a community organizer of rent strikes.

–His photojournalism work selling photographs to the New York Post.

–His Top 5 pictures, including the Sikh photo and the judge’s comments.

–More on the flash mob photos at the Golden Spike. Including his memory of Phillip Choy.

Podcast link:

Emil Guillermo is a journalist and commentator. He writes a column for the North American bureau of the Inquirer.net. Contact: www.amok.com