A young Fil-Am’s life well spent among those who have the least

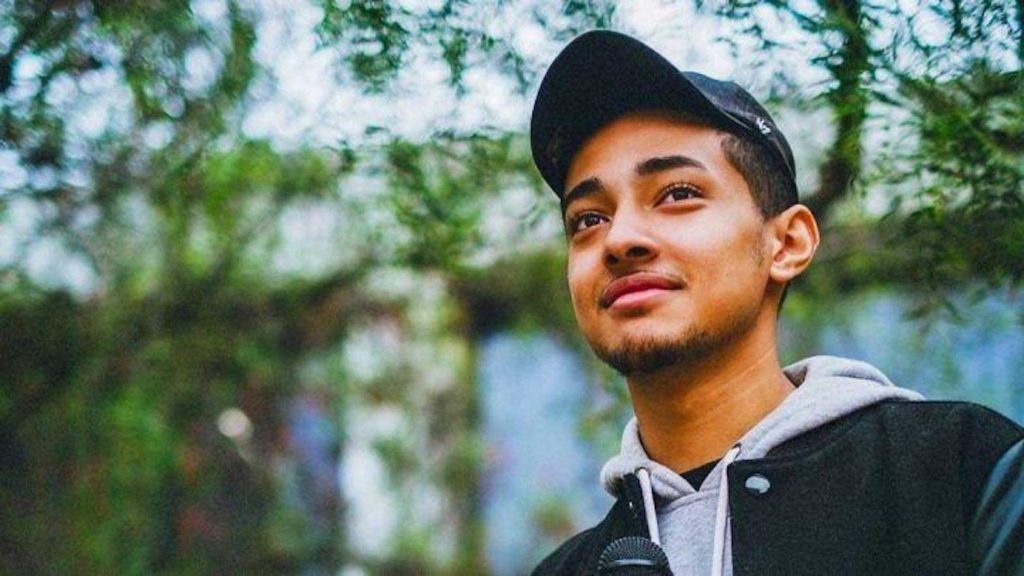

Amado Khaya Canham Rodriguez, Fil-Am activist, passed away from septic shock in the Philippines. CONTRIBUTED

OAKLAND, California – At a young age that held a promise of great things to come, Amado Khaya Canham Rodriguez had already done and experienced much. He had been living with indigenous communities and farmers in the Philippines, standing with them in their fight for land, livelihood, and ancestral domain for months, when he died at only 22.

Rodriguez, an activist, community organizer, and beloved son died on Aug. 4, 2020 in Mindoro, Philippines, from severe food poisoning.

Born on May 9, 1998, Amado was “stubborn from the start,” coming into this world after 30 hours of labor. “That was a very challenging experience,” says Robyn Magalit Rodriguez, PhD, Amado’s mother who is an immigrant rights and antiracism activist as well as an author and professor and department chair of the Asian American Studies at the University of California, Davis. “They actually needed to give me Pitocin, but it was all natural, no epidural. After that, it was like a couple of pushes later then he was out.”

Robyn Rodriguez is also the founder of the Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies that is noted to be the first Filipino studies center in the United States.

Amado was an epitome of multi-ethnicity, cross-culturalism, and diversity. His mother was born in the San Francisco Bay area to immigrant parents with roots in Aklan, Capiz, Ilocos Norte, and Pangasinan in the Philippines, while his father, David Edward Canham, is a South African immigrant with roots in the Transkei of the Eastern Cape and descended from the Mpondo Xhosa people.

For years, Amado was called “honey boy” by his parents because of his “gorgeous brown skin tone and his ultimately sweet and loving personality” that was complimented with an “angelic face” with “beautifully shaped eyes and endless eyelashes.” “People would often remark at how angelic his face was and how he looked so much like a Santo Niño—rosy cheeks and these big, big eyes, very long eyelashes, and a happy, joyful disposition,” says Rodriguez. “That description of him as a baby also reflects his character. He had this conviction but also a very sweet and loving disposition that he had for the rest of his life.”

Social justice and activism had been a part of Amado’s childhood and upbringing with both of his parents being activists and organizers. After immigrating to the United States, his father worked primarily as a labor organizer. But it was a path that was not necessarily expected of Amado to take. “Of course, that’s no guarantee, but, certainly, he was in a context where questions of justice were so much a part of and integrated into our lives.”

Amado working a campaign. CONTRIBUTED

Amado had various interests growing up, from drawing to martial arts to athletics. Any of which could have pursued having had ample skills for each. Yet it was his relationships with people that gave a clue to his initial leanings towards social justice. “The best indications were just in the nature of his friendships with people. Those were the seeds where you can identify some kind of quality, an orientation towards others, that could lead on this pathway.”

Born and raised in Oakland with a stint in New Jersey before moving back to Oakland at 13, Amado’s worldview was shaped by the stark inequalities he saw and experienced in life. He felt marginalized as a biracial Black student from Oakland attending California High School in San Ramon with a largely White and affluent student population. It was his connections with the few Black teachers at the school that provided motivation and fueled his passion in reactivating the Black Student Union with the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement after the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012. He continued to be involved in Black Lives Matter after graduating from high school.

Amado was always drawn to people in the margins. A diagnosis of moderately severe hearing loss with a dependence on hearing aids for the rest of his life furthered his awareness of being different and fostered his sense of identity.

“Even in preschool and kindergarten, he just tended to gravitate and wanted to be friends with people who were around the margins. Those might have been the beginnings of his consciousness,” says Rodriguez. “And when he, himself, had to depend on hearing aids and was very aware of being different, maybe that helped propel a kind of desire to do social justice work. That became much more clear, this feeling of outsider-ness.”

Amado saw each day as an opportunity to learn and gain a deeper understanding of the world around him. “I think it was something he carried. He had a curiosity about him. He loved to learn. He just read voraciously and pushed himself to just explore different forms of knowledge.”

His appetite for knowledge equaled his love for all kinds of food as a visceral way of learning about people and culture. “He loved to eat. Because he’s so slender of build, sometimes it’s almost impossible to imagine how much he could scarf down a whole buffet. He loved to try out new food because it was a lens into culture.”

It was as a student in Laney College in Oakland that Amado exhibited his ability and first realized his power as an activist and community organizer. As one of the young leaders fighting against gentrification, he was instrumental in the successful halting of the construction of the A’s ballpark at the Peralta Community College District headquarters. “I think that that’s what he tapped into. He was really just so effective at it.”

Witnessing Amado’s increasing bent towards social justice work and his emergence as an activist, his mother was well aware of its implications and dealt with it with care and understanding. “You try to cultivate your values, ethics, orientation to the world in your children, but I was always actually very careful about not being heavy handed about it. I tried to provide a lot of loving support without pushing. There are already pressures there that I don’t have to impose on him. Some of it is very self-imposed, in part, because everybody else is making assumptions about what kind of person you must be or ought to be or what you are going to be just by the mere fact of who your parents are. That’s already pressure enough.”

Amado had lived in the Philippines as a toddler, but it was his trip back there as a teenager where he first had a glimpse of the path that he would take. It was the start of a series of trips that would have a profound effect on the budding activist and humanitarian. He and his mother visited historical sites and learned a lot about the country’s history. “I remember my own experience and that was why I wanted to bring him there when he was 13,” says Rodriguez. “I remember my own first family trip to the Philippines at that age and it was so meaningful and impactful for me.”

Following a family trip in 2016 after graduating high school, Amado decided to join the International Committee for Human Rights in the Philippines. He was the youngest person in an exposure trip to lumad communities and where he also met with various workers and students across the country. “I was, ‘Yeah, there’s so much you’ll be able to learn in just a matter of months that you wouldn’t learn in a semester in a Filipino studies class,’” says Rodriguez.

When Amado came back, he was changed. “It was one thing to learn about the kinds of injustices that happen in the Philippines then to see it with a very different set of eyes. By the fall of his second year, he was changed, just really humble, because, in a lot of ways, he was like a little brat sometimes; I mean, young boys, right, don’t clean up their room, are lazy about helping with the chores… he was all that. He was so thankful for every meal I made, all of a sudden his habits were changing, he was tending to everybody, cleaning up and all that… He just wanted to make a change in himself and to do this work.”

Robyn Magalit Rodriguez with baby Amado. CONTRIBUTED

Amado wanted to learn more and more about the Philippines. “He wanted to understand the totality of the Philippines.” At the time, Amado was a Sociology major taking classes in labor studies at Laney College. He had become more involved with activism and organizing including efforts against gentrification and worker’s rights. “He started working with caregivers with the Pilipino Association of Workers and Immigrants (PAWIS). He would chit chat and learn from the workers with what they’re dealing with. He was helping to teach them to drive. He would go to the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), he would hang out for hours in the office and would just listen to his peers, and then he would go to the Filipino Education Center (FEC), and then he would come back to Laney. He was just soaking it all up and wanting to do stuff about it. Slowly but surely, it was becoming clear that he just wanted to go back to the Philippines.”

In 2018, at the age of 20, Amado pursued his chosen path by going to live and work in the Philippines. It was a trip he would not come home from. “When you’re a young college student, lots of possibilities open up but it is clear that the Philippines was an important part of it,” says Rodriguez. “Initially his plan was to go for another short stint. After that, he found his element somehow. He really relished being in the Philippines. It felt like home to him. He was very resourceful. At some point, he was just driving his own itinerary. I just would hold my breath and hope that he’s fine. Before you know it, his return ticket date comes and he was like, ‘Sorry mom, I’m not coming home.’”

Indigenous issues were very important to Amado. He travelled around the country working with indigenous communities. “I remember how disturbed he was when he went to Boracay. It was hard for him seeing the [state of the] Aeta (Ati) community throughout Panay.”

While working for a development group in Batangas in late 2019, right before the COVID-19 pandemic, a devastating typhoon had hit Mindoro. Amado joined the disaster relief team. “He went there because there was real need of direct relief and to check on communities to see how they were doing. That’s where he was by the time the pandemic hit.”

Amado lived and worked with the Mangyan community and farmers in Mindoro. “That was so important to him. He really wanted to learn and the indigenous communities was where his heart was.” But communication with the outside world became a challenge. “Yes, everybody has a cellphone but if you’re really trying to be with marginalized communities, it is hard. There would be times when the reception would just be enough for texts and barely a facetime or Facebook video call.”

When the pandemic hit and with the lockdown and restrictions that ensued, Amado was stranded in Mindoro. Although he was at a place where he was doing what he loved to do, the unsettling reality, limits, and uncertainty that the pandemic brought took its toll. “Just like all of us, lockdown, especially in the early days, was hard. He was just ready to take a break and come home.”

Yet Amado was torn between his concern for his family and his own welfare and that of the indigenous and farming communities. “He struggled with what it meant to be able to leave that, come home to a life of privilege, and then sticking it out.”

In an unfortunate turn of events, Amado was struck with a severe case of food poisoning. Unable to avail of immediate medical treatment due to lockdown, he succumbed to septic shock. “His Filipino name, ‘Amado’ means beloved, and his South African name, ‘Khaya’ means home. He died doing the work of literally building homes for the poorest of the poor in the Philippines. That was preceded by work of fighting to preserve affordable homes in his city of birth. We think of activism in certain kinds of ways but for Amado, activism was about being kind and loving. He was just incredibly a fiercely loving person. There’s no other way to describe it.”

Rodriguez says, “My job now is to tell his story. I’m hoping that his story can serve to inspire. We can all see a bit of ourselves in a person like him. I want young people to feel like, ‘Hey, I can be just like that guy. Do I struggle in school? He did too. Do I have a disability? He did too. Am I Filipino; am I Asian? He is. Am I Black? He is. Am I a child of Immigrants? He was. He was all sorts of things. He wasn’t the class president, he wasn’t the valedictorian, he wasn’t the star athlete. In a lot of ways, he was just a normal kid. But he was a normal kid who also wanted to put light and love into the world. And a lot of young people can feel that way too.”

As Ehgosa Hamilton, Amado’s former teacher at California High School said, “Let’s lift up his memory and remember his legacy. He is the new ancestor that has carved out a new path and way of being. He is the success story we need to celebrate. He is the epitome of humanity.”

All photos contributed by Robyn Magalit Rodriguez.