“Lorenzana’s incoherent statements portraying Diliman as some sinister haven and training ground for terrorists underscore the reality that when it comes to Duterte and his thugs, military intelligence is an oxymoron.” INQUIRER FILE

Anybody who’s trying to understand the thinking behind the Duterte dictatorship’s aggression against UP Diliman should remember what happened in 1976.

That was when another dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, sent his security forces to silence the Philippine Collegian, UP’s respected student paper, arresting its top editors, led by editor-in-chief Ditto Sarmiento.

That’s what Duterte’s thugs led by Defense boss Delfin Lorenzana are fantasizing about: they think they can intimidate and bully a community long known for being a bastion of courage and defiance.

There’s just one problem: the campus that the Duterte dictatorship is looking to shut down IS a bastion of courage and defiance. The more you try to bully and intimidate the Diliman community, the stronger the resistance you’ll face.

That’s precisely what happened 45 years ago.

Marcos sicced his military on UP Collegian for dating to speak out against his dictatorship — against the corruption, the abuse of power, the torture and the violence.

“The time has come for us to take action and not lie silently about as our rights increasingly become trampled upon,” Ditto Sarmiento wrote in a 1976 editorial. “The time is now, for if not now, when?”

The Collegian staff punctuated that message with what became the UP paper’s most famous front page, and one of the most iconic images and slogans in the history of the fight against the Marcos dictatorship.

The Collegian front page featured an illustration of the UP Oblation with the banner: “Kung Hindi Ngayon, Kailan Pa?” [If Not Now, When?] At the bottom of the page, the staff: “Kung Hindi Tayo Kikibo, Sinong Kikibo? Kung Di Tayo Kikilos, Sinong Kikilos?” [Who will speak up if we do not speak Up? Who will act if we do not act?]

The Collegian paid a big price for that act of defiance. Sarmiento and the newspaper’s top editors were arrested. A frail young man, he subsequently became ill in prison. He was eventually released, but he never fully recovered. Ditto Sarmiento died in November 1977. He was only 27.

It was a victory for Marcos. One of the dictatorship’s most vocal critics had been silenced. But Ditto Sarmiento’s journey of courage did not end with his death. His staff kept on fighting.

It’s important to provide some context here. That assault on the UP Collegian took place at a time when there was no Twitter, no Facebook, no social media. Heck, there wasn’t even a decent traditional media to speak of. The papers, the TV and radio stations were controlled by the dictatorship.

There was no outrage in cyberspace over their arrests. No protest memes. No hashtag campaigns. The Collegian staffers were isolated and alone.

They could have chosen to just keep quiet. But they fought back instead.

To honor their fallen editor, the Collegian ran a special edition of the paper in 1977. Emblazoned on the cover were the words: “Para sa iyo, Ditto Sarmiento, sa iyong paglilingkod sa mag-aaral at sambayanan.” [“For you Ditto Sarmiento, for your service to the studentry and the nation.”]

Again, the front page featured the Oblation, UP’s symbol. But instead of his arms outstretched, Diliman’s naked man had his fist raised to the sky, having broken free from chains.

The dictatorship killed a young man who dared to fight back — but it was not able to kill that young man’s message, his call to action against a brutal regime.

Now, Duterte, who inspired a brutal campaign of mass slaughter and has brazenly attacked anyone who opposes his dictatorship, is resorting to similar tactics.

Lorenzana’s incoherent statements portraying Diliman as some sinister haven and training ground for terrorists underscore the reality that when it comes to Duterte and his thugs, military intelligence is an oxymoron.

The list of alleged NPA members that the military published underscores this. It was a ridiculous list that included respected Filipino in the arts, media and civil society, including two of my close friends, the renowned playwright Liza Magtoto, and Lisa Dacanay, an internationally-known trailblazer in social entrepreneurship.

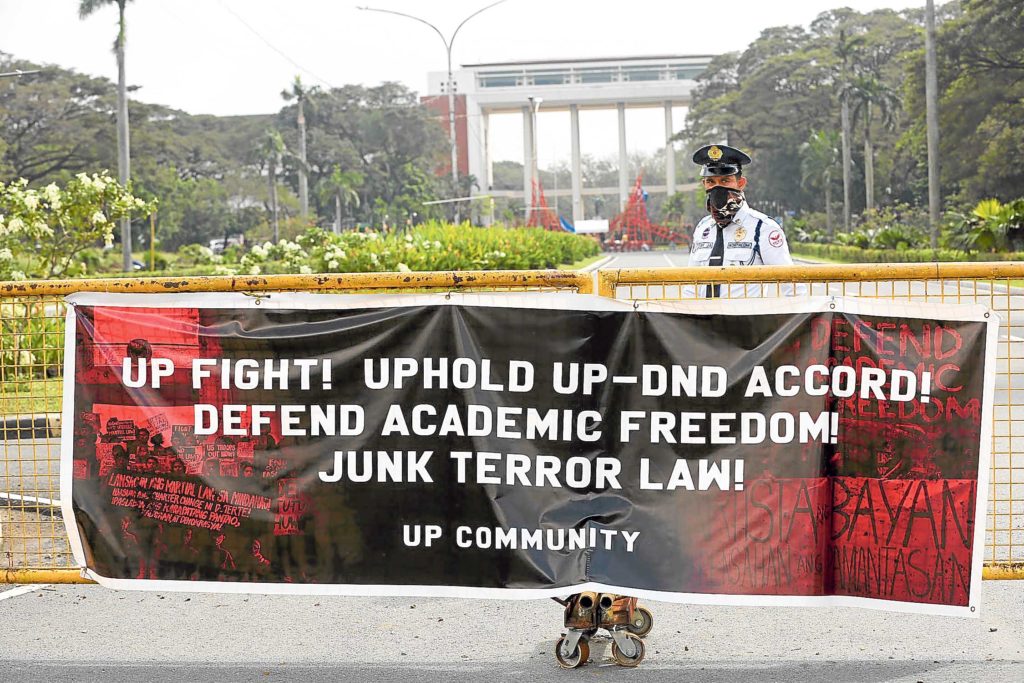

Clearly, abrogating the UP-DND agreement is aimed at giving Duterte’s security forces more ability to do some muscle flexing in Diliman.

Lorenzana probably has this crazy idea that they could now simply send troops marching down the academic oval and into Palma Hall and then, suddenly, a community with a long and proud history of standing up to thugs would cower in fear.

Police and military thugs on Diliman? Diliman has plenty of experience with that — and as Ditto Sarmiento’s heroism showed, Diliman will resist.

The campus bore the brunt of the Marcos crackdown after martial law was declared in 1972. And UP students fought back. Quietly and secretly at first. Then openly and with total commitment to ending the dictatorship.

Open protests were banned in the early years of martial law. So students embraced creative tactics. One of them was the ‘lighting rally.’ A small group would march from the third floor of Palma Hall to the second floor, yell slogans and unfurl banners, and then quickly put those away and disperse before police arrived.

The protest would be long enough for the activists to let other students know, “Don’t let these bullies deceive you. There are many of us who want to fight back — and who are fighting back!”

By the time I entered UP in the early 1980s, activism was an established part of UP culture. Being a UP student meant being prepared to face off with bullies. Now, I am a bit ashamed to admit it took me a while to embrace this view. As a freshman, I remember listening to the scary stories of older students who recalled the violent clashes with police at Liwasang Bonifacio.

I wasn’t eager to be part of such confrontations. But that was part of what being an Iskolar ng Bayan meant in the 1980s during the final years of the Marcos dictatorship.

In July 1984, UP staged a series of marches, led by our student council chair Lean Alejandro, on Mendiola toward Malacanang. By the third successive march, word went out that Marcos was getting really pissed.

I was then editor of the Collegian and about an hour before the start of our third march, on July 6, 1984, I had a meeting with Lean who confirmed that there were reports the dictator had had enough.

“Titirahin daw tayo. They’re going to disperse us,” Lean said.

“Tuloy ba natin? So do we go on with the march?” I asked.

It was a dumb question from someone who was supposed to be a UP activist, and Lean answered immediately: “Of course.”

Of course, we were not going to back down. Of course, we were not going to let ourselves be intimidated by a thug. Of course, we were going to march despite the threat of violence from a bully.

We got tear-gassed that afternoon, forced to disperse before regrouping near Espana. The dictator won that round. He showed us who’s the boss.

But not for long.

The following week, on July 13, UP students were back. This time there were more of us, including delegations from other schools and other sectors. We know what happened afterward. An even bigger demonstration finally kicked the dictator out.

Lean was assassinated a year after Marcos was overthrown. It was a tragic, devastating blow to the Diliman community and to many of us who saw him as the most important leader of our generation.

But as Duterte and Lorenzana consider mindless tactics to bully Diliman, they should spend time understanding Lean’s impact on the UP campus. They can start with Lean’s famous quote: “The line of fire is the place of honor.”

Not every UP student would embrace that view, certainly not those from the elite universities for whom the place of honor is the corner office or the corridors of political power or the presidential palace.

But that statement defines Diliman, a campus, a community that consistently, defiantly stood on the side of those who are being bullied, with the underdog.

Lean is known for another quote that defines Diliman, and which probably represents an even bigger problem for Duterte, Lorenzana and the thugs who think they can intimidate a community that has proven again and again is not easily intimidated.

Lean once said: “The struggle for freedom is the next best thing to actually being free.”

The Kuwento page on Facebook