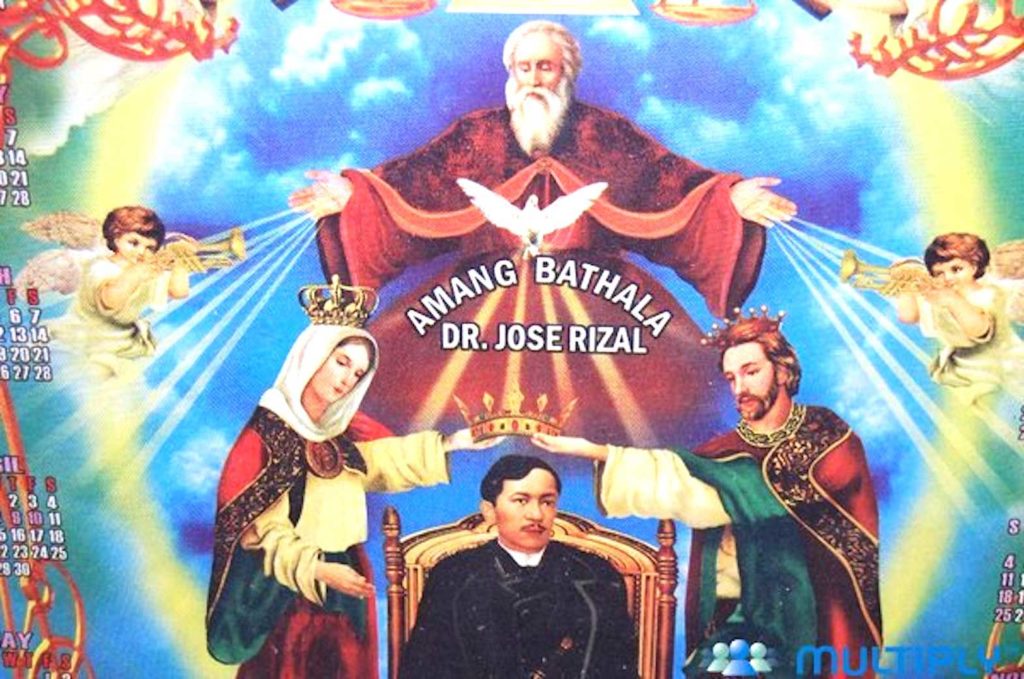

A number of homegrown religious sects, particularly those in and around Mt. Banahaw—often described as the mystical, magical mountain—venerate Rizal either as a saint, a manifestation of God, or a later incarnation of Christ.

NEW YORK—December 30, 2020, marks the 124th anniversary of José Rizal’s execution by the Spanish colonial government in 1896. The ilustrado had written two novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, that portrayed the colonial regime, particularly the friar orders that constituted a state within a state, as deeply corrupt, racist, and long devoid of any spirituality. Convicted during a mock trial largely orchestrated by the friar orders, the 35-year-old polymath was taken to Bagumbayan (now Rizal Park), where at around 7 a.m. he was gunned down by firing squad. It is said that onlookers rushed to dip their handkerchiefs in the martyr’s blood, signaling how the nation would approach the man.

Seeing him today with fresh eyes is difficult, given his status as national hero, even deity. Practically every town throughout the archipelago has an avenue named after him, and every plaza has a statue of the man, invariably in his overcoat. And volumes have been written about him, enough to fill a whole library. Much of the literature leans towards or is completely hagiographic.

A number of homegrown religious sects, particularly those in and around Mt. Banahaw—often described as the mystical, magical mountain—venerate him either as a saint, a manifestation of God, or a later incarnation of Christ. Among these are Ciudad Mistica de Dios, Banner of the Race Church, Iglesia Sagrada ng Lahi, Iglesia Sagrada Filipina, and Samahan ng Tatlong Persona Solo Dios.

While largely adopting Catholic or Christian rituals, such as the Mass, these groups stress a feminized hierarchy, as a not-too-subtle putdown of Western patriarchy and as an acknowledgement of the principal role women have long had as babaylan, or spiritual and community leaders. And including Rizal in their theological canon is a nod to the anticolonial and pro-independence spirit kept alive by these groups and their small but devoted following.

In 1914, General, Artemio Ricarte, who fought with Emilio Aguinaldo in both the 1896 revolution against Spain and the subsequent Philippine-American War of 1899, declared that the Philippine Islands, as it was then known under the colonial rule of the United States, should be renamed, according to Nick Joaquin’s A Question of Heroes, “as Rizaline Islands and its people Rizalinos. The terms ‘Filipino’ and ‘Philippines’ were to be abolished but the Philippine flag was to be kept. The Rizaline Republic, when established, would ‘recompense’ all those who had joined the ‘Liberating Army’ to ‘overthrow quickly and by whatever means the present foreign government,’” a clear reference to the US colonial administration.

Ricarte had refused to pledge allegiance to the US and was by then living in exile in Japan, earning his bread by teaching Spanish in Tokyo and running a restaurant in Yokohama. (I’ve always wondered what that restaurant was called and what was on its menu. I imagine the items proffered would be dishes that Ricarte missed from his native Ilocos region.)

During World War II, when his host country had defeated the US Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), the Japanese flew the aging general to Manila hoping that his endorsement of Japanese rule would inspire his fellow Filipinos to accept being part of Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with its slogan of “Asia for Asians.” By then the general’s revolutionary stature had faded; if in the late nineteenth century, the revolutionaries looking to the Japanese as liberators made sense, by the 1940s, it was foolhardy.

The impoverished populace had come to loath the Japanese Imperial Army due to its brutal policies and longed for the return of US forces that once were viewed in a hostile light. Ricarte was ignored or worse, viewed as a traitor, a collaborator.

With the return of General Douglas MacArthur and his army in 1944, Ricarte fled north with the Japanese command, to the Cordilleras, where he, in poor health, perished in July of 1945. Though he had instructed his aide Colonel Konochiro Ota, presumably in Spanish (Ota had been his student in Tokyo), per Joaquin, “to erect my tomb both in the Philippines and Japan,” no tomb or marker has been found.

One question that should be asked: What would Jose Rizal, a hero in the general’s eyes, have made of Ricarte’s actions? (To be continued) Copyright L.H. Francia 2020