Ifugao myths make sense of archeological finds

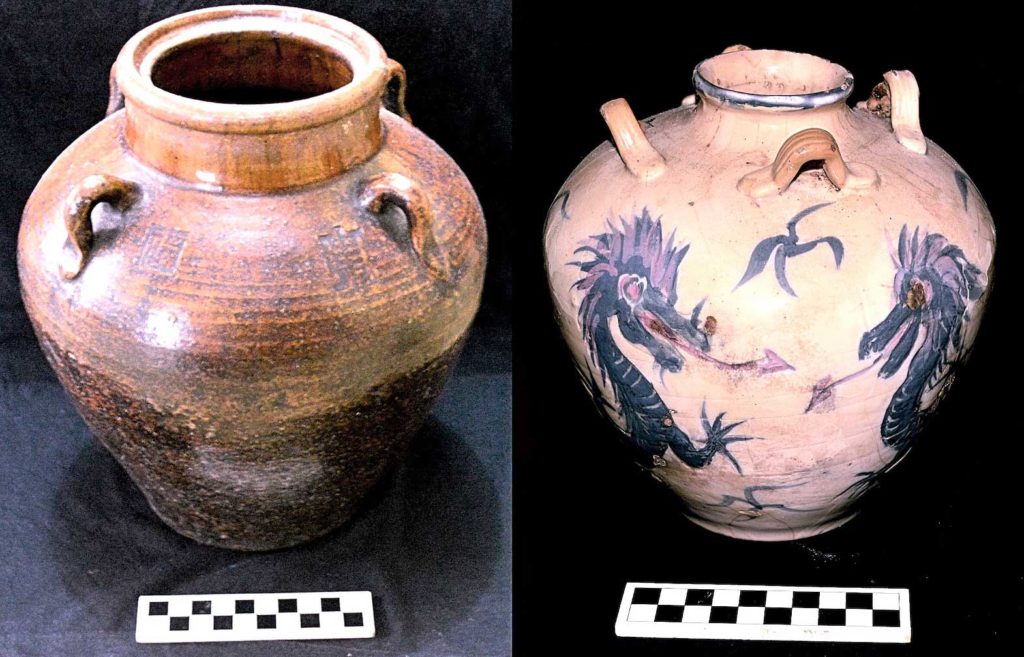

Heirloom tradeware jars in Ifugao. Right: ginayyaman (dragon jar) and galgalit (white and blue Ming jar).

“There she lies beautiful, Kiyyangan, a village west of Kadaklan, the Great River. Where all things started. Surrounded by the three sacred peaks, home to the most powerful earth spirits, sentinels to the gods. For is she not a child of the skyworld, Kabunyan?” (Ifugao Creation Myth)

The recent auction of an Ifugao hagabi (wooden bench) that fetched $460,000 brings to fore the loss of cultural properties and increasing economic marginalization of Indigenous peoples. In the Philippines, this is a continuing process that started during Spanish colonization, reinforced today by nationalized Philippine history curricula. The Philippine colonial experiences, from the Spanish, to the US, to the present-day nationalistic fervor, have erased the existence of Indigenous peoples in historical narratives.

If we are to redress Indigenous peoples from the economic and political oppression, we can start with providing tools to reclaim their history and heritage. In this essay, we highlight our work in Ifugao, where the Kiangan (Ifugao) community has taken control of and is conserving its heritage through the interweaving of archaeology, history, and community stories.

The Ifugao are known for their majestic rice terraces, previously claimed to be at least 2,000 years old but are now dated to about 400 years old. What most Filipinos don’t know is that these rice fields allowed the Ifugao to resist the Spanish conquest and facilitated their participation in the colonial economic world. This new historical narrative is based on archaeological research and community interpretations of the artifacts recovered from the Old Kiyyangan Village (OKV).

Kiyyangan is mentioned in Ifugao creation mythology as the first village to be inhabited by the Ifugao. There are different versions of the myth, but they consistently refer to the Kiyyangan as the location of the first village in Pugaw. This was confirmed by the myth documented by Roy F. Barton, a pioneer American anthropologist, which was provided by Pumihic Pablo, a mumbaki (Ifugao religious specialist) of Puitan, Banaue and was confirmed by two other mumbaki from Bo-oh village in Banaue, Tabayag and Pahitte.

The Batad rice terraces, one of the five terrace clusters listed in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The settlement was first documented in a letter by Fray Juan Molano to his Father Superior in 1801, indicating the village had 183 houses and 4,000 inhabitants (a very large settlement of that time). This letter was also the first to describe the existence of rice terracing complex in Ifugao. When the Americans reached the region, the Old Kiyyangan Village was already abandoned, and its inhabitants relocated to the present town center of Kiangan.

The Kiyyangan Valley and its stories

Archaeological investigations uncovered thousands of potsherds from several trenches. A number of intact pots with infant remains have also been unearthed. Ifugao elders still remember the burial jar practice since it was only about fifty years ago that pottery production ceased to exist. Accompanying the burial jar is the custom of burying stillborn, infants, and children under their houses. This practice is based on the old belief that burying the infant or child under the house will keep it a secret from the deceiver gods, the cause of such tragedy.

No ceremonies are conducted, no animals are sacrificed (adi madangliyan) and mourning is not allowed for the death of a child. Funerary textiles that normally shroud an Ifugao dead are dispensed. Doing otherwise will encourage the deceiver gods to take more children as they take great pleasure in the suffering of the Ifugao. The only material thing that the child is donned with is a string of arm beads, an amulet to keep any soul snatcher at bay as it journeys alone to the afterlife.

Jars and beads, local or imported, played a role in the lifeways of the Ifugao. Nobles are bedecked in layers of gold and gold-foil, carnelian, agate or glass beads in the performance of their feasts of merit. They wear them during their funeral, though imported beads, unlike textiles, were rarely buried with them. The “soul stuff” (inanimate power) of the object is bestowed on the departed through magical incantations during the burial rites. Same thing goes with the mandatory animal sacrifices (dangli) where the meat is consumed by mortals and the soul stuff offered to the legion of ancestors and divinities in the Ifugao pantheon.

A scene from the animated film “The Old Kiyyangan Story.”

Pottery was a local merchandise among the villagers of the Kiyyangan. A neighboring village, Mungayang, less than a kilometer away, produced the finest earthenware potteries in the district until the craft was rendered obsolete by the influx of lowland merchandise during the American period. These earthenware ceramics were used as cooking pots and water containers.

Imported tradeware, stoneware, and porcelain, obtained from lowland merchants were preferred as fermentation jars for the much-prized rice beer, bayah, an essential commodity in rituals and community feasts. Stoneware ceramics have always been identified with the Ilocanos, Christianized lowlanders from northern Luzon who have been resettled by the Spanish through the reduccion policy, in what is now the provinces of Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya. Stoneware jars are much more common, though less valuable, compared to Chinese porcelains.

Porcelain jars have always been highly prized by the Ifugao. It has acquired purchase and redemption value, so much so that it was used as a currency to pay off debts, purchase rice fields and exchanged for slaves prior to the coming of the Americans. It is also an object of antiquity among the Ifugao as they have evolved specific terms for particular designs, e.g., ginayyaman for dragon jars, galgalit for the expensive white and blue Ming jars, binullangon for Vietnamese brown jars with lion stud handles and dinolman for the more common smooth brown jars.

While the Ifugao generally associate these imported porcelains to the Chinese as they do their beads, the origin is not as important as the story that comes with it on how it was passed down from ancestor and so on until it reaches the present possessor – the longer the story of its ancestral provenance, the more expensive it is.

Knowledge co-production

The Ifugao origin myth and other community stories help make sense of the archaeological findings from the Old Kiyyangan Village. Without the knowledge passed down by the ancestors, scholars are left to hypothesize about what happened in the past. However, the active involvement of the Kiangan community in the pursuit to learn about their past provide us with the tools to claim Ifugao history as told by Ifugao themselves.

These community stories do not contradict the archaeological findings; rather, they complement each other. More importantly, community stories serve as a counterpoint to colonial and nationalist narratives and serve to facilitate the decolonization of history. The story of the Old Kiyyangan Village and the short history of the terraces represent how Indigenous history empower descendant communities. As an example of this narrative, the Kiangan community initiated the development of an animated video that details how the Ifugao successfully resisted Spanish conquest.

The story of the Old Kiyyangan Village is a story of Indigenous peoples struggles against historical hegemony. Using Ifugao heritage as an example, we argue that a deeper understanding of Philippine Indigenous history is not only empowering, it is also meaningful as it makes us perceive history from the standpoint of the Indigenous. Incorporating Indigenous explanations and community stories facilitate conversations about the colonial foundations of Filipino identity.

Stephen Acabado is associate professor of anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles. His archaeological investigations in Ifugao, northern Philippines, have established the recent origins of the Cordillera Rice Terraces, which were once known to be at least 2,000 years old. Follow him on twitter at @stephen_acabado.

Marlon Martin is the Chief Operation Officer of the Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement, a non-profit heritage conservation organization in his home province of Ifugao, Philippines. He actively works with various academic and conservation organizations both locally and internationally in the pursuit of indigenous studies integration and inclusion in the formal school curricula.