What it takes to be a foreign student in the U.S. now

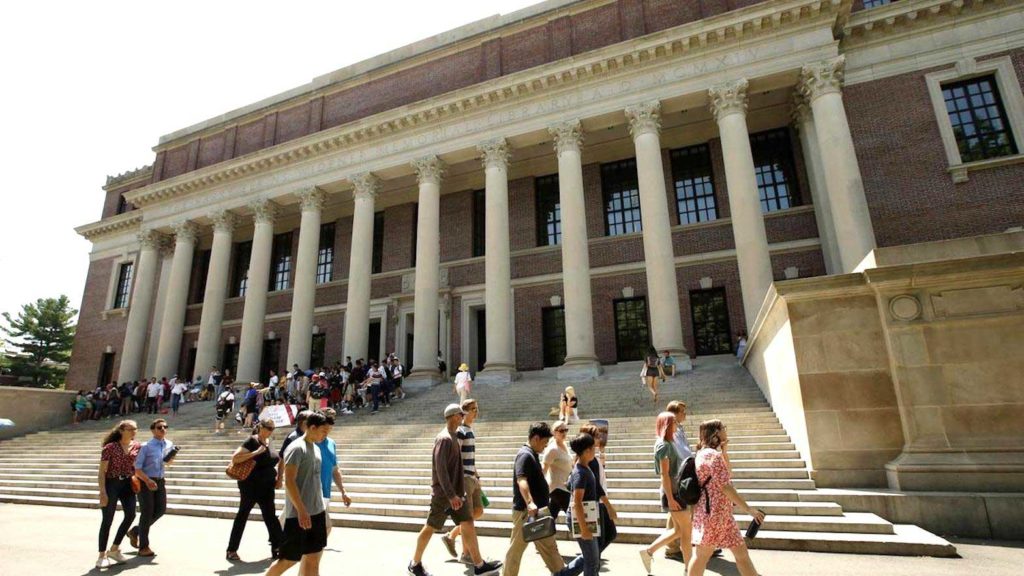

Many US institutions depend on the arrival of new international students each year. AP

When my grandfather left the Philippines for his master’s studies in 1949, it took over a month to travel from Manila to Michigan. Three weeks on a ship to Hawaii, then another week of sailing to San Francisco, before a long train ride to the Midwest. When my dad came to Chicago in 1977 for his master’s, it was free to apply for visas at the US Embassy on Dewey Boulevard by Ermita, which was the center of Manila then. By 1983, when he returned for his doctorate, it wasn’t free anymore.

Later renamed after President Manuel Roxas, the boulevard was originally named for the American admiral who defeated the Spanish in the Battle of Manila Bay in 1898 — fought six weeks before the Philippine Declaration of Independence. Seven months later, the Treaty of Paris let the US buy the Philippines from Spain for $20 million. Today, that $20 million in 1898 dollars is worth about $600 million.

By the time I came to the US to study law, we no longer had to pen messages to our loved ones on paper and entrust them to the vagaries of the post office. We didn’t need to spend fortunes on phone cards to call our loved ones back home like we did up to the early 2000s. Our smartphones now allow us to call, text, or beam memes or cash instantly around the globe.

For the duration

One thing that all three generations had in common was that we all interviewed at the same US embassy and all came to the US as F-1 international students. After inspection at the border, our Filipino passports were all stamped “D/S” – which stands for duration of status. This means that F-1 students are generally not admitted until a certain date like B-1/B-2 tourists, J-1 exchange visitors, or K-1 fiances serving their 90 days.

So long as they are fulfilling requirements from the school and from the US government, international students can stay in the US as long as they maintain status. This includes taking a full-time course load, being current on your tuition bills, keeping a clean criminal record, and updating the US government if you move and change addresses. Skipping class too much can make you fall out of status.

Typically, students stay until they graduate, and then have another year of optional practical training to work in fields related to their degrees. This idea is key for doctoral students like my father — because any graduate student can tell you that it generally takes years of writing and defending your dissertation to achieve your degree. He finished in six years, but still had classmates toiling away at theirs decades later.

All x equals y

You’re probably part of many groups. You work, study, worship, or play somewhere. You’re part of a family, of multiple friend groups, maybe associations or other organizations. If you’re reading this, you might identify as Filipino, Filipina, Fil-Am, Pinoy, Pinay, or Filipinx, or maybe an even smaller slice related to province or dialect. Maybe you already have a green card or a blue passport, or maybe that’s your dream.

Maybe you’re second- or third-generation and immigration is a distant family memory, along with the Filipino language. The US Constitution enshrines birthplace citizenship for everyone born in the United States, regardless of their parents’ immigration status or lack thereof. The only exception covers the children of diplomats who have diplomatic immunity and thus aren’t subject to American law.

Many Fil-Ams who came here “the right way” have a tendency to look down on others. One question though: how would Americans tell the difference? We can change our accents and adjust our fashion sense to be more “American,” but we’re still branded by the color of our skin, the shape of our noses, our love of karaoke, or our height. US immigration law places immense importance on country of birth, and US culture and life marks us as Filipino even in the white coats of doctors, the tailored suits of lawyers, or the masks of Jabbawockeez.

Reverse brain drain

Factors like economics, history, and the policies of both the US and Philippine government have traditionally caused a brain drain from our islands to the US mainland. A recent proposal from the US Department of Homeland Security might flip that. On September 24, DHS proposed eliminating Duration of Status admission for F-1 students, J-1 exchange visitors, and I visa holders — foreign media that are coming to the US from home offices in the Philippines or other countries solely to engage in work for foreign information media outlets.

Under the proposed rule, F-1 international students would not be allowed to stay in the US for the duration of their status even if they are otherwise complying with American law. They would only be admitted for a maximum of four years, or until the program end date marked on their I-20s. J-1 exchange visitors such as nurses, doctors, or medical students would face similar restrictions.

Worse, the Philippines appears on a list of 50-some countries whose students and exchange visitors have more than 10% overstay rate. This means that if this proposed change happens, Filipino F, J, and I visa holders would be limited to a max of two year visas. This is not enough time to finish a doctor’s, master’s, or almost any advanced degree. Filipino students studying regular BA or BS college degrees would be forced to submit requests for extensions of stay in the middle of their programs, which costs not only money, but time and the stress of possibly being denied and having to abandon their investment in an American education.

Immigrants make America great

America is great because of its immigrants. A 2018 study showed that over 50% of the US’s billion dollar startups had an immigrant founder. While students are technically non-immigrants, many international student graduates go through the yearly H-1B lottery that only a third succeed in winning. That gives them a working visa tied to an employer that hopefully renews them after it expires, or even better, sponsors them for permanent residency, making them legal immigrants. Others fall in love and marry Americans. The Fil-Am community is quite integrated. We have one of the highest rates of intermarriage, and one in five Fil-Ams identifies as multiracial.

Other graduates, like my father and grandfather, take what they learned in their American education back with them to the Philippines. Many of our Presidents, Vice-Presidents, and other political and business leaders do the same. The US has always been a shining beacon of education. Cutting-edge research, discourse, facilities, and knowledge are found here, and unlike almost any country other than Germany, American colleges and universities sometimes even give scholarships to international students.

The days of someone with a high school education that works a labor-intensive factory job easily being able to afford a big house and car and life are long gone in both the US and the Philippines. Knowledge is power, and education is a means for students to grow and learn and eventually benefit both countries. Those who care about higher education and the future can only hope that reason will prevail over rhetoric, so that Filipinos can continue to learn from America’s best and brightest, and shine even brighter.

Jath Shao is a lawyer and writer who is passionate about building the Fil-Am community. He helps Filipinos and other immigrants achieve the American dream.