In the Time of COVID: ‘Love life and it will love you back!’

Dr. Virginia “Ginny” Pineda-Garcia, a pediatrician and volunteer with Doctors Without Borders, advises: “Love life and it will love you back!” CONTRIBUTED

TORONTO—A doctor-friend from Pasig in Metro Manila emailed me mid-March, after the coronavirus pandemic had upended the world, sharing how strange it felt waking post-COVID.

“Would you believe? With Covid…no traffiiiic, clean air, no human beings on the streets. Many shops are closed, schools, malls, hardware stores. But it’s sad to note that for people who live with day-to-day work—and now, no pay—they will have to struggle doubly hard.”

Looking back, she added, “I am glad you read through my photobook…iyan ang aking (that’s my) ‘memoirs’—tama ba ang spelling?—or my autobiography. Sabi nga (as they say), after a few doctors dying suddenly, eh maghanda na tayo ng mga memoirs (let’s get memoirs ready).”

“Covid can attack us any time, especially very vulnerable old people. But after having been to Laos and Nepal in Asia, and to Sierra Leone and Ethiopia in Africa, including the community here in Pasig where I have served for 45 years working with the underprivileged, eh itong ‘death’ is a common thing, so less fear for me.”

So, I responded:

“COVID-19 is a message of caution, a message for us to keep track of what we’ve done to ourselves, and to our world.

“It is frightening to not know if we will get it. Then what happens next? Will we survive it?”

I shared how I felt sad and at a loss. Each morning I’d wake up and ask myself, is it safe to even walk out for an hour to buy groceries?

We had not stocked up for the months that the news media told us it would last. Up to June, they say.

We are only good for a month at the most. Some sardine and tuna tins, a jar of peanut butter, some pasta, a little rice, dried beans.

We’d planned to go for a quick visit to the little supermarket in our neighborhood once a week to get fresh produce.

I’ve also planted garlic cloves and tomato and green pepper seeds in our small backyard. I hope to harvest in a month or so.

Then I asked my friend how she has prepared herself.

Since she has seen some of the worst cases in her practice, working in various danger spots across the globe, I told her she must think I exaggerate.

Our FB Messenger is saturated with predictions and worst-case scenarios. Also, numerous calls to prayer.

And unceasing fear that those near to us have either succumbed to the virus or have lost their jobs or livelihood.

I then asked my friend: “Please reassure me that we will survive this unscathed.”

And then she replied after a few days.

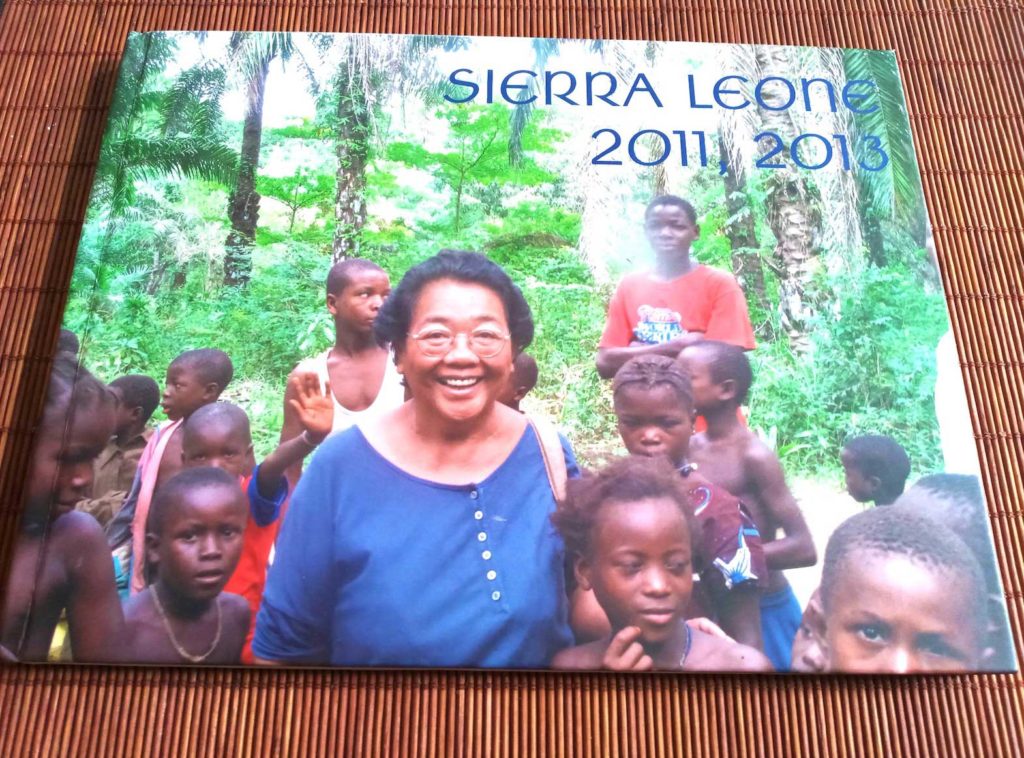

Dr. Virginia “Ginny” Pineda-Garcia’s book on her stint in Sierra Leone. CONTRIBUTED

“Everything in this world passes by. They become one way or the other part of our past but then we have to deal with the present now. Good planting gives us hope. Hope is a virtue we need. Once we plant each day, the seeds grow and then develop branches, leaves, and fruits or flowers. This is the result of the love we planted.

“In my tour of Laos refugee camps, I attended to infants convulsing and dying—150 deaths in one month! At that time, I didn’t think about when it would all end. Every day I WORKED, trying my best to save their lives. I don’t even remember praying…. It was just work, work, work…until there were no more patients coming and the epidemic ended.”

To ease her emotional load, my friend said she grew a small garden in the refugee camp, planting beautiful flowering plants.

During the encephalitis outbreak 1979, she would sit beside the mother of the infant who was convulsing and cry with her as she pleaded to save her son’s life since he was on the ONLY one left. The woman’s husband, father and mother died during the war in Laos, where American forces dropped bombs every eight minutes: 80 million bombs from 1965 to 1975.

So, she concludes, “What we are now having is not sooo different or greater than what I had seen. Nevertheless, we address every stage in our lives doing the best we can.”

Today my friend employs two house helpers since she tires easily. She calls it “easy fatigability.” Her house has seven rooms and they get dusty EVERY DAY (she has put this in all caps for emphasis)—”This house was built 36 years ago as a 42-sq. meter house with one toilet, one bedroom and dining room.” Now after 36 years, she has added rooms, a garage, a garden on the second floor as well as a third-floor small room on a tower overlooking all her flowering plants and trees: ylang-ylang, champaca, boungainvillea, kamuning, kampupot, sampaguita. At 70, she adds, “I cannot possibly attend to all these.”

The one-month quarantine in the Philippines has given her special moments to enjoy all her labors—planting flowering plants—as well as moments to remember all the places and people she has met. She has a roomful of photos from those travels, including paintings of women in different parts of the world: Myanmar, Vietnam, Japan. Her husband Oliver too has lined up favorite oil paintings he did from 2000 to 2015.

And, of course, the everyday quarantine gives both of them the “pleasure” of listening and watching their only grandchild grow. He’s now 11 years old.

in the time of Covid, my friend of many decades, Dr. Virginia “Ginny” Pineda-Garcia, a pediatrician and volunteer with Doctors Without Borders, advises: “Love life and it will love you back!”

•••

Dr. Virginia Pineda-Garcia, left, with Hmong refugees, 1980. She contracted tuberculosis while attending to her patients in the Laos refugee camp. She was 179 lbs. when she first arrived, and weighed 90 lbs. when she left the camp. CONTRIBUTED

Birthing in the time of COVID

As if hiding from the virus would save me, at 70, and having served as a doctor for almost all my lifetime—45 years in practice, I decided to open my clinic at my home recently.

So, yesterday I delivered a five-month-old fetus—fetal death in utero—and had to deal with a fragmented placenta. Extraction was difficult because the cord was thin and fragile. I had to do a manual extraction.

Being a community doctor, I learned all these tricks over the past 45 years without going through an actual obstetrics residency.

Years ago, I remember being in a refugee camp at the foot of Mekong River between Laos and Thailand, during the secret war of the C.I.A. –from 1965 to 1975—when 80 million bombs were dropped in Laos to kill the Vietcongs.

I was on duty that night; meaning, the only doctor in the camp with 45,000 refugees and three wards—pediatrics, obstetrics and internal medicine. There was a woman in labor, and she was convulsing, having an eclampsia. I had to give her valium and oxygen. The newborn I had to extract with a vacuum cap attached to her head and maneuvered by my foot—you need to pump, pump, pump to make the baby come out alive.

In the same emergency room that night was another woman actively bleeding from an abortion. Her hemoglobin was so low I needed to transfuse blood. A refugee donor lay down beside her. We got his blood and directly transfused it to the mother. Remember that in this place there was no blood bank, only a medical technologist to examine blood type and cross matching.

A third woman had a fetus stuck into her birth canal, and I could not extract it out. The following morning, when our van arrived from town—a two-hour drive—I brought her to the town public hospital. Since the travel was rough—bumpy roads along the zigzag mountain terrain of Thailand—the fetus came out by itself, just as we entered the hospital gate.

That was my life in 1979, inside the Hmong refugee camp. —Dr. Virginia Pineda-Garcia, M.D, Pasig, Metro Manila