Moving on from America’s dark past in PH Part 1

The volume of Anti-American rhetoric in the Philippines grew louder recently. Bolstered by the current administration’s efforts to pursue an independent foreign policy of sorts, many citizens have chosen to support a neo-nationalist narrative, which asserts that in totality, the U.S. had not helped but hindered the Philippines by advancing a century-long agenda of exploitation against Filipino interests and sovereignty.

If such a trend of anti-Americanism were to persist, it would amount to a complete reversal of longstanding popular sentiments. In its annual survey of 39 key countries around the world, The Pew Research Center showed the Philippines scoring at the very top of its “U.S. Favorability” survey across the study’s entire 16-year period; a whopping 92% of Filipinos favored the U.S. as recently as 2015.

Yet, the most fervent of nationalists maintain that this former colonial master’s historical transgressions and exploitative practices against the Philippines should force a substantial foreign policy shift today—one that ushers the country’s exit from U.S. economic and military orbit and abrogates existing treaties and agreements.

U.S. colonial rule: a sordid history

No doubt, the early period of U.S. involvement in the Philippines was a very dark blight on modern history.

Emboldened by the prospects of an alliance with the U.S. at the start of the Spanish-American war in 1898, Filipino resistance fighters succeeded in pushing Spanish forces in the Philippines to the brink of defeat. Three hundred years of European rule would end when U.S. forces finally arrived in Manila Bay to symbolically strike the final blow.

But General Emilio Aguinaldo’s proclamation of national independence on June 12, 1898 proved to be premature. U.S. president William McKinley chose to annex the Philippines instead at the Treaty of Paris just six months later.

During the 14 years that followed, from the start of hostilities in what would become the Philippine-American war of 1899, some 34,000 heavily outgunned Filipinos would be killed in the early fighting as countless war atrocities were committed by American soldiers against the populace.

Within this fairly unknown chapter in world history, Filipino freedom fighters in the northern Philippines and Moro rebels in the south would be systematically decimated by the U.S. Army. A staggering 250,000 civilians (estimates go as high as 1 million) would perish as victims of malnutrition, cholera, and violent military conflict. In stark contrast to the slaughter of a large percentage of the Filipino population, only 4,200 U.S. casualties would be sustained throughout the war.

World War II: liberation and betrayal

After a more peaceful period in the ‘30s with an autonomous Filipino commonwealth established, and national independence within sight, the Japanese attack on Clark Field, just hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, would usher in another tragic era. Filipinos would be drawn into the bitter fighting of World War II, this time, side by side with U.S. forces.

More than 10,000 Americans and Filipinos would perish in the fighting leading up to the fall of Corregidor in 1942. And over 20,000 more would die during the forced Bataan Death March and in Japanese captivity. By the end of a bloody period of Japanese occupation in 1945, some 25,000 Americans and 60,000 Filipino soldiers would die liberating the Philippines.

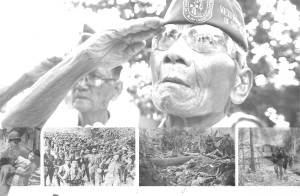

Shortly after the war, a blow would be dealt to the 260,000 Filipinos who fought under the American flag in the Pacific theater of military operations. Despite U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s promise of full veteran’s benefits for the Philippine Commonwealth Army, incorporated with the U.S. Armed Forces in 1941, Filipino veterans of World War II would be stripped of disability pay, U.S. immigration rights, and other benefits by the notorious Rescission Act of 1946.

Passed by the U.S. Congress shortly after Philippine independence was granted, the Rescission Act reversed the official status of Filipino fighters as having been in the service of the U.S. military during the war—making Filipinos the only group out of 66 nations allied with the U.S. that did not receive military benefits.

Post-Philippine independence: evicting the U.S.

In the next three decades after World War II, a newly independent Philippines would be embroiled in a lengthy struggle to end a series of unfair U.S. trade agreements beginning with the Bell Trade Act of 1946 and its Parity Amendment which tied the Philippine economy to the U.S. and provided Americans the same rights to Philippine natural resources as Filipinos.

After World War II, the last major vestiges of U.S. occupation in the Philippines would be projected from their two largest overseas military bases, the massive Subic Bay Naval Station and Clark Airbase, both under government lease until a nationalist movement pressured the Philippine Congress to evict the U.S. military from both facilities in 1991.

Righting the past

Looking back at this long history, it is a travesty that very little about the Philippine-American war is widely known, nor is the story reflected accurately in the historical record. It would be difficult to hold the blame for this injustice over the heads of the current American population as diplomatic leverage though—100 years have passed and no decision maker or participant in that dark period survives to this day—but there’s much to be done by America to restore the honor deprived from its Filipino participants.

And while the sacrifice of thousands of Americans who gave their lives toward the liberation of the Philippines in World War II should not be diminished or forgotten, it is unfortunate that today, the stories of triumph and suffering of Filipino soldiers and citizens have largely been written out of the American World War II narrative.

More importantly, unlike those affected by the Philippine-American War, 18,000 surviving Filipino veterans of World War II are still with us today. In a move to address past grievances, President Obama signed into law an act establishing the WWII Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund in 2009, which earmarked $198 million to be paid out to Filipino veterans. New efforts underway include a 2016 program to fast track the U.S. immigration process for veteran’s families. In November, the U.S. Congress passed a bill to award the Congressional Gold Medal to Filipino World War II veterans.

Whether this is all too little too late is a matter of debate. But using these historical resentments against the U.S. as a present-day foreign policy determinant may open up a world of contradictions: the Japanese, despite being directly responsible for the deaths of up to a million Filipino civilians; and having unleashed on the population some of the most vile war crimes ever perpetrated in history, are at present held in high regard in the Philippines.

Today, Japan is the Philippines’ top trading partner, with trade worth $19 billion in 2015 alone, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. Japan is also among the top direct foreign investment partners and foreign aid donors to the Philippines.

History is not policy

It would be all too easy to steamroll any present-day ties between the Philippines and the U.S. under the weight of this very complicated history. But we need to be reminded that relationships with another nation must be contingent on the virtues of their present-day iteration—not of their identity from a distant past. We must focus on their current ideologies, actions and intentions.

It would be unfair to regard anyone with contempt based on their distant ancestor’s transgressions; relying on historical events from long ago as a measure of any nation’s present value is also impractical. Consider: by going back just two generations, hundreds of countries that are currently at peace were once bitter combatants.

The reality is that the America that was once a colonial master of the Philippines is long gone. Just as we know that the Belgium of King Leopold, the Cambodia of Pol Pot, or the Germany of Hitler are no longer the same nations who perpetrated the mass genocide of millions in Africa, Asia, and Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries.

So reasonably, unless a former transgressor is unrepentant; still inequitably enjoying the spoils of its past aggressions; maintains the same caustic ideologies; or harbors the same malicious intents, then their ancient history should be left for perpetual remembrance and reflection by all—but it should not preclude the cultivation of present-day relationships.

Certainly, there still remain some historical wrongs to address. Efforts should be doubled until all veteran’s rights are restored for Filipino World War II soldiers, and more effort needs to be made to revise the historical record so they accurately and honorably reflect Filipino involvement in wars they fought with and against the U.S. And critically, a reckoning of scars from past colonial oppression is also in order—so some formal expression of regret can finally be heard from America in order to help Filipinos heal their ancestral wounds.

The history of Philippine oppression by the U.S. must never be forgotten—indeed it must be revised and retold. But in order to continue forging productive partnerships with other countries—critical for a rapidly developing nation—the people of the Philippines and their leaders will need to stay focused on the present, and the many opportunities that lie ahead.