NEW YORK—This year is the birth centenary of Nick Joaquin, born on May 4 and who in 2004 died in his sleep at his San Juan home.

Honored by the Philippine government as National Artist for Literature in 1976, Nick—short for Nicomedes, a name he wasn’t overly fond of—was a versatile writer who wrote in all genres, from journalism to fiction, from to poetry to biographies, from plays to cultural criticism. The amazing thing is, he made a name for himself in all these.

Penguin Classics has just come out with a collection of his works (not including his poetry or his reportage), Nick Joaquin: the Woman Who Had Two Navels and Tales of the Tropical Gothic, with a foreword by Gina Apostol and an introduction by Vicente L. Rafael. This edition includes his landmark drama, A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino: An Elegy in Three Acts.

This is the fourth book of Philippine literature that Penguin Classics has issued, the previous three being the two novels by José Rizal (translation by Harold Augenbraum), Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, and the poetry of José Garcia Villa, edited by John Cowen and with my introduction.

These inclusions under a venerable and prestigious imprint have come about through the efforts of Penguin Classics’ Vice-President and Publisher Elda Rotor, a Filipina-American, who had worked previously at Oxford University Press. I knew of her initially as a poet and included her work in the anthology that Eric Gamalinda and I co-edited in the late 1990s, Flippin’: Filipinos on America. Elda deserves a whole warehouse of credit for enlarging the readership of some of our most revered writers.

Here is a previously unpublished essay that I wrote some years back on Nick.

In the Time of Nick

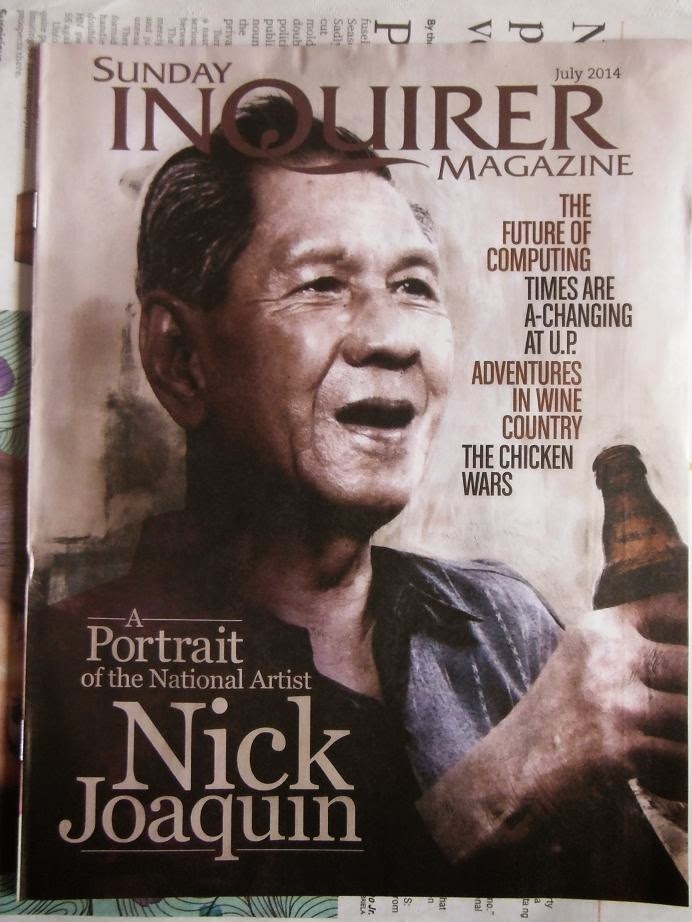

When was it I first met Nick? The earliest image I can dredge up from the mental archives of a young man just beginning his twenties is Nick at the cafeteria of the Free Press, somewhere in Makati. And it has him holding a bottle of San Miguel beer. Jose “Pete” Lacaba introduced us, so Pete is in that picture, too. Pete, a cohort of mine at the Ateneo de Manila, had dropped out during our senior year and began working at the weekly magazine, pursuing the craft of journalist and wordsmith, and Nick was one reason—likely the main reason—Pete was at the Free Press.

Then again, on that particular occasion, Nick may not have had a beer, but even if this recollection is inaccurate, it isn’t false. For St. Nick and San Miguel may have been separated from birth but were now and forever inseparable, two halves of a bubbly whole. As to the parlor-game question of whether there is beer in heaven, I am convinced there is, otherwise the celestial realm would have been split by Nick’s howler of a voice, once likened by José Garcia Villa to an air-raid siren.

I hadn’t as yet read his fiction or his poetry—that was to come later on, when I had joined the never-ending exodus of the young and the restless to Greenwich Village in Manhattan. But I certainly had read the journalistic pieces he had written under his nom de plume, Quijano de Manila—transformative work that alone made purchase of the Free Press a necessity.

I was one among countless younger writers whom Nick befriended, and of those I believe it was just Pete and I who had studied at the Ateneo; most of the others seemed to have been from the University of the Philippines at Diliman. Our appellation for him, St. Nick, wasn’t just wordplay but an indication of his generosity. For Nick was the patron saint of those of us just beginning the arduous trek through the forbidding terrain of language, hoping to discover our own paths. Whenever we would sally forth into the night in his company, he was always taya, picking up the tab for food and drink, paying for cabs. I am certain he also, and quietly, helped a few writers who were down on their luck.

Of course, he knew and hobnobbed with the other bright lights of the literary establishment. He was good friends with the poet Virgie Moreno and my older cousin the late Larry Francia, and thus came to befriend my oldest brother Henry and his fiancée Beatriz Romualdez. Henry and Betsy, both now departed, wed in 1969. I missed the wedding held at Malate Church as I was by then living in Montreal, but from the press clippings my father sent me, clearly, it was one of the year’s notable social events. If my memory of those clippings (since lost in a fire) is right, Nick was a sponsor. He had worn a Barong Tagalog over a turtleneck, maybe the only instance of Nick playing the fashionista. It was a hippie wedding, and here was Nick’s chance to be part of the Sixties, if only fleetingly.

Nick showed up occasionally at Los Indios Bravos in Malate, the happening café owned and managed by Betsy, and where assorted writers like myself, artists, lost souls, intellectuals, hustlers, and pretty colegialas hung out. But his favored haunts were the small, smoke-filled dives of Manila’s demimonde, with jazz and Sinatra the music and crooner of choice. Who can forget Nick’s delicious (sometimes delirious), sly rendering of “You’re the Tops”? You heard him before you saw him. He had a distinctive laugh that was at once a cackle and a loud hoot.

Villa, by the way, had immense respect and fondness for Nick both as a person and a writer, and described the best of his stories as “world-class.” I couldn’t agree more. In compiling my 1993 anthology of Philippine literature in English, Brown River White Ocean, for Rutgers University Press, I decided to include him in both the “Short Stories” and “Poems” sections. Of his stories, I picked “The Summer Solstice”—its intense eroticism, its unforgettable portrait of a Hispanicized late-19th century haut bourgeois couple whose conventional marriage is upended by the Tadtarin, a powerful pre-Christian ritual centered on the female, render it a masterpiece.

He could be gruff and play the world-weary cynic, but in reality he was a sweetheart, his hail-fellow-well-met demeanor concealing a writer who could write like the best of ‘em. Yet Nick never put on airs, equally at home hobnobbing with the glitterati and the literati or having beers with cops at some hoi polloi joint. The last vivid image I have of Nick in fact is of seeing him, on one of my balikbayan trips, with a whole row of Manila’s Finest listening to a girl band at a Malate club and contentedly drinking their, what else, San Migs. As usual he was the benevolent paterfamilias, so there was no question of my paying for my beer and pulutan. Nick was like that, a true democrat. Tolerant and humorous, his was a rare illuminating and playful presence.

It is said that memory is all we bring into that looming good night. It was my good fortune then to have known such a brilliant, humane writer—good fortune that as I get older grows even more valuable no matter how many times I mine it.

You’re the tops, Nick.

Luis H. Francia / Copyright 2008/2017