Watsonville Anti-Filipino Riot, a reminder of bigotry gone berserk

Filipino farmworkers in California in the 1930s. The Watsonville riot targeted Filipinos for consorting with white women. UC ARCHIVE

There’s a small Filipino American community in Watsonville, California (pop. 54,000), scene of one of the worst racially-driven attacks against Filipinos 90 years ago, that also helped define the Filipino diaspora in the United States.

Watsonville is hardly a household name for most Filipino Americans. Dioscor Recio Sr. was barely out of his teens when he moved to this farming town in 1928. The place prospered on the backs of migrant labor – Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino sacadas who received scant wages for long hours in the field, their white employers often pitting one group against the other to ensure they always got the cheapest, most productive workers. What was to be known as the Watsonville Riot was five days of bloody mayhem on January 19-23, 1930. White marauders attacked every Filipino they could find on the streets, including 22-year-old Fermin Tobera.

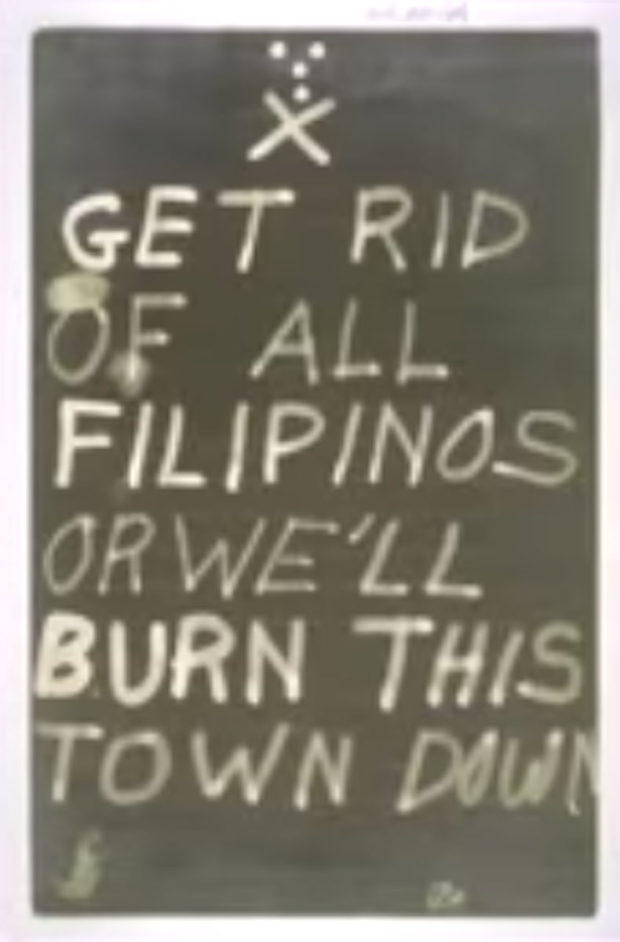

An anti-Filipino sign circa 1930s.

“There are no Filipino markers to signify us and our history,” Mr. Recio’s son Ray told the website pajaronian.com. His father Dioscor Sr. passed away in 2018. Last October, the younger Recio led a “Community Call Out” to remaining survivors and their families to share their stories, and this week he helped people to remember.

“I want to bring them forward, to get people involved and excited,” he explained. “We have made huge contributions to this town’s history, this is the time to highlight that.”

The Equal Justice Initiative also posted the story of the Watsonville riot on its website:

“Beginning on Jan. 19, 1930, mobs of up to 500 white people roamed Watsonville, California, and the surrounding towns and farms, attacking Filipino farmworkers and their property after Filipino men were seen dancing with white women at a newly opened local dance hall.”

The EJI account noted that “In the days and weeks before the rioting, politicians and community leaders had ramped up their anti-Filipino rhetoric, calling the farmworkers ‘menace’ and demanding that Filipino residents be deported so ‘white people who have inherited this country for themselves and their offspring could live.’”

The Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924 allowed Filipinos to take advantage of the growing demand for labor on the US mainland, and became the dominant Asian farm labor force in the 1920s to 1930s.

Filipinos were often assigned to the backbreaking work of cultivating and harvesting asparagus, celery, and lettuce. Employers saw Filipinos as docile and pliable, and were often used to counter the perceived “laziness” of working-class whites and other ethnic groups.

The Watsonville Riot began outside a Filipino dance club in the Palm Beach section of Watsonville. The club was owned by a Filipino and offered dances with the nine white women who lived there. The mob came with clubs and weapons intending to take the women out and burn the place down. The owners threatened to shoot if the rioters persisted, and when the mob refused to leave, the owners opened fire.

Mobs dragged Filipinos from their homes and beat them. Shots were fired into their homes. The police in Watsonville, led by Sheriff Nick Sinnott, gathered as many Filipinos as they could rescue and guarded them in the City Council’s chamber while Monterey County Sheriff Carl Abbott secured the Pajaro side of the river against rioters.

The violence eventually spread to Stockton, San Francisco, San Jose, and other cities. A Filipino club was blown up in Stockton. Fifty unemployed whites and Filipinos were hustled out of town by police, trying to preempt possible fighting.

The body of Mr Tobera, who was shot in the heart while he hid in a closet from the marauders, was brought home and extolled as a martyr of American injustice and inequality by advocates of Philippine independence.

Filipino immigration in California plummeted after Watsonville and they began to be replaced by Mexicans. In 1933, California enacted a law to prohibit marriages between Filipino and white residents.

But seven months after the riots, Filipino lettuce pickers carried out a successful strike in Salinas in 1934 and then reprised it in 1936. They became one the catalysts for the development of the Filipino labor movement in America that would be carried to fruitition two decades by Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, Chris Mensalvas, et. al.

On Sept. 4, 2011, California apologized to Filipinos and Filipino Americans and in an Assembly resolution authored by Assemblyman Luis Alejo.

“Filipino Americans have a proud history of hard work and perseverance,” Mr. Alejo said in a statement. “California, however, does not have as proud a history regarding its treatment of Filipino Americans. For these past injustices, it’s time that we recognize the pain and suffering this community has endured.”

According to EJI, no one was ever charged with Mr. Tobera’s murder. Seven men were later convicted of rioting, but received either probation or 30 days in jail.