The color of July Fourth

Before June 12, there was July 4. My first history lesson came from my mother when I was six years old, when she took me to a July Fourth Philippine Independence Day parade at the Luneta.

Waving a small paper Philippine flag, she told me, “We should be thankful to the Americans for giving us independence.” It was 1954, and Diosdado Macapagal, who would change the date of Independence Day to June 12 in honor of the 1898 Kawit declaration, had yet to become president. July 4 had yet to be changed to “Philippine-American Friendship Day.”

If gratitude for American benevolence was then the popular attitude towards the Great Power it was understandable; the memory of U.S. soldiers storming back to the Philippines to end four years of brutal Japanese occupation remained fresh and vivid.

I still remember seeing my Uncle Amado watching television coverage of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s final visit to Manila in 1961. When the general sentimentally declared that he had “returned again,” my uncle, a big bull of a man, wept like a child in his rattan chair.

Unfortunately, the first casualty of our sentimental education was the truth. In reality, less than honorable self-serving motives led to the American promise and eventual grant of Philippine independence.

In the late 1920s a worldwide economic depression combined with a domestic agricultural slump refueled calls in America for Philippine sovereignty. The main lobbyists were cottonseed and dairy interests opposed to the free entry of Philippine coconut, the cordage lobby against abaca hemp, the beet sugar bloc backed by the Cuban cane lobby versus Philippine sugar and the American Federation of Labor against Filipino immigrant labor. As the Depression deepened, moves accelerated in Congress for setting the Philippines free. But an equally convincing, or perhaps even more powerful, impetus for the calls for independence was white Americans’ fear of racial dilution. A May 1, 1924 San Francisco Examiner editorial, for example, harrumphed that with the exception of “peoples of Caucasian blood” inassimilable races and “inassimilable people must generally be barred from the United States.”

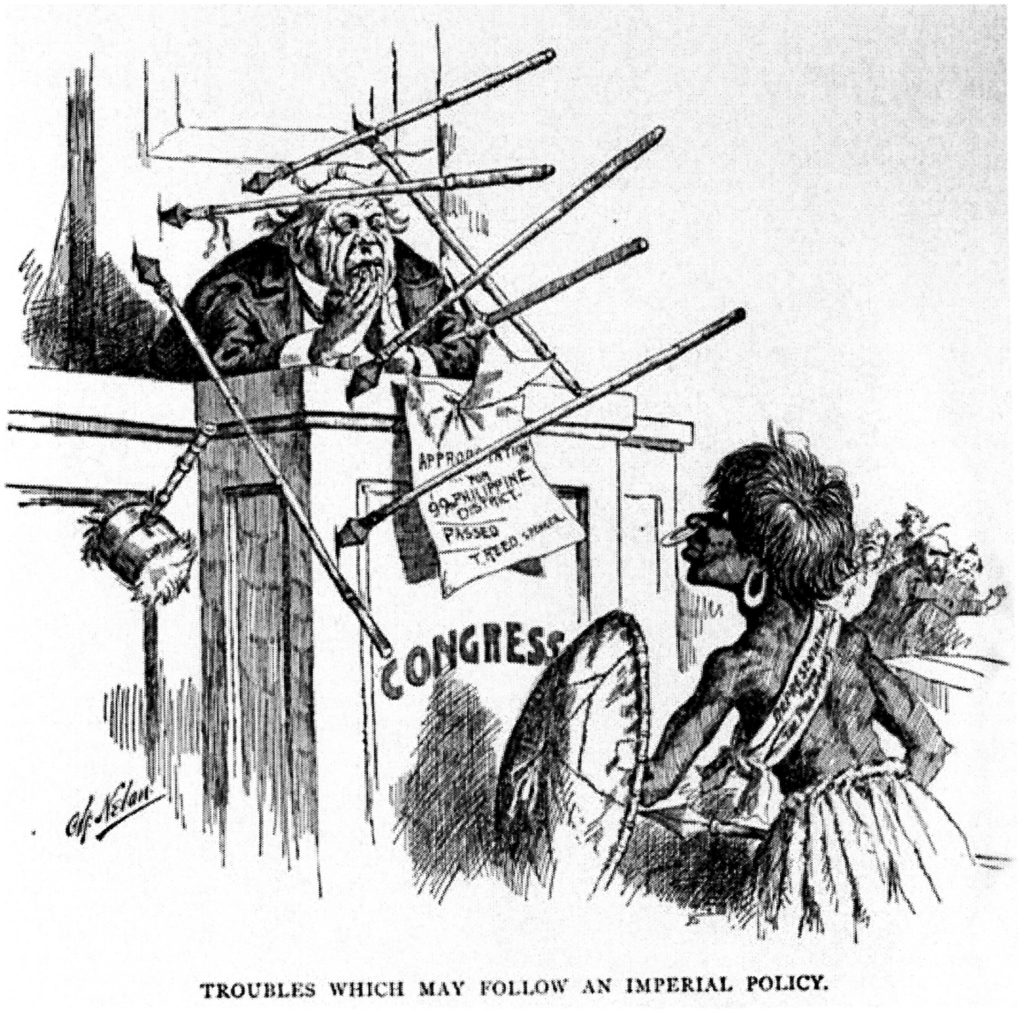

It was a period in America when pseudo-scientific and Social Darwinist racial theories that “proved” the “natural inferiority” of non-whites still held sway. Historical records show that most public officials, both national and local, still subscribed to a racially hierarchical view of the world, with Anglo-Saxons at the very top.

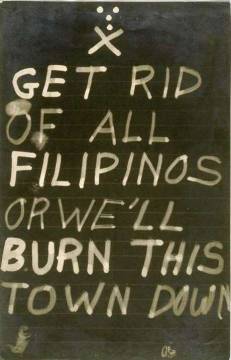

White supremacy had been the principal argument against granting self-rule to the “little brown brothers” and the genetically “tainted,” half-white mestizos at the top of the Filipino social ladder. All were unfit for self-government, the reasoning went, and only the Anglo-Saxon race could do it right. By the late ’20s, however, this reasoning had been turned on its head. The supposed racial inferiority of Filipinos had become the rationale for Philippine independence. Why the switch? By the ’20s, thousands of Filipino men had been recruited by burgeoning agribusiness in Hawaii. By the early ’30s upwards of 50,000 largely single Filipino men had come to the U.S. West Coast as itinerant farm workers. As subjects of an American colony they were considered U.S. nationals. Their presence, however, ignited social tensions. Many Filipinos figured in labor unrests. There were racist attacks on Filipinos who fraternized with white women. Laws against miscegenation were enforced. Filipinos’ presence in America became a roiling controversy. A San Francisco Chronicle editorial on April 5, 1932, departing from the paper’s strident opposition to Philippine independence, now called for fixing a date for it. It complained that, “In the last two years (the issue) has been growing troublesome, with the immigration problem making it more so. Once a definite date is set for independence no one, not even the Filipinos can object if we tell them to stay at home in the meantime.”

In the same spirit, the chauvinistic American Federation of Labor led the charge in Congress for the granting of independence as the mechanism for revoking the status of Filipinos as U.S. nationals, transforming their status into aliens excludable from entry. Finally, on March 24, 1934, the Tydings-McDuffie Act provided for complete Philippine independence after a ten-year period of preparation. (World War II would delay its implementation.) Tellingly, the Act included a provision limiting the entry to the U.S. of the now officially alien Filipinos to 50 immigrants a year. A border fence made of the promise of Philippine national independence was erected to keep out Filipinos.

Ironically, the racial supremacist ideology that spurred the conquest and colonization of the Philippines would also be the cause of its formal separation from the United States. Fear of the influx of “inassimilable” colonial subjects convinced the American policymakers of the period to scuttle the white man’s burden.

I believe I failed to correct my mother’s sentimental understanding of Philippine-American relations before she died at age 88. Perhaps I never really wanted to spoil the warm memory of my first history lesson from her on that festive afternoon in July 1954. My Uncle Amado, too, went to his grave a political and historical innocent. He died at a relatively young age of 50, felled by the imported, unfiltered, blue-seal Pall Malls that he loved to chain-smoke.

(Revised version of “The Color of Independence” published in Filipinas Magazine, June 1, 2007.)