Why Bishop Salazar convoked First Manila Synod in 1582

He was moving heaven and earth within the period of his actual episcopate from 1581 to 1594 — 13 long and tough years sans PLDT, Meralco, Manila Waters, MegaMall, Cebu-Pacific, Chatbot, smart TV, and other convenient gadgets of the new millennium. Bishop Domingo de Salazar, OP, had more than a few things to accomplish, too meager resources to use, scours of souls to save, and too few co-laborers in the field.

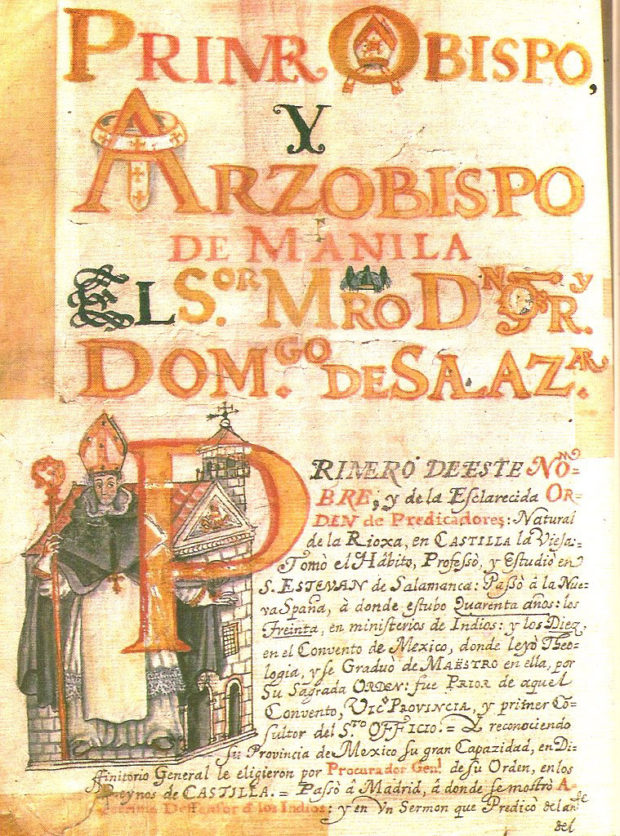

Pure courage always coexisted with holiness in the man of the cloth. The first Bishop of Manila dauntlessly fought for the downtrodden, for those wala-nawala-at-binalewala (ignored, dismissed) sector of society, and espoused the cause of the Filipinos with valor that won for him the title of “intrepido Salazar.”

The first conflict between Church and State took place in 1581, precisely when, upon his arrival, Bishop Salazar exerted his ecclesiastical authority, his sense of justice, and his paternal charity to protect the autochthonous people against the authoritarian rule of the Spanish conquerors.

Spain, the most powerful state at the time, saw some cultures as “second-class civilizations,” a subculture that distanced the conquerors “from the reality of a people” and separated them from the natives, surely a “disrespect of humankind” (borrowing the words of Pope Francis, Synod of Bishops for the Amazon, October 7, 2019).

When Bishop Domingo de Salazar, OP, was troubled, deeply troubled, by the multiple reports of the abuses Filipinos suffered at the hands of Spanish soldiers, guardia civil, and other functionaries, he convoked a synod of the clergy a.k.a. the First Manila Synod of 1582, which was later confirmed by Pope Gregory XIII, in order to address the problems.

Preferential option for the weak

His love for the poor made him sell his own pectoral cross, one of the few material things he possessed, in order to buy and distribute provisions of food and clothing among the natives.

As historiography show, the Augustinians, Dominicans, Jesuits, Franciscans, and the Recoletos were champions of the weak and the poor. Pope Francis himself in our time has to remind the Filipino bishops: “The poor are at the heart of the Gospel, if we take away the poor from the Gospel we can’t understand the whole message of Jesus Christ.”

Salazar drew a line in the sand and pointed out to the Spanish functionaries the limit of their authority, and that limit was characterized by social justice for the less privileged. His efforts and those of other missionaries tempered the ruthlessness that often marred the Spanish governance of our people.

He was unstoppable. With old age unable to reduce his zeal, he set out for Spain one last time; imagine, when he was almost eighty. Accompanied by Fray Miguel de Benavides, OP, founder of the Universidad de Santo Tomas, he took the perilous journey of several months by sea to plead in person with the King the good cause of the natives.

Exhausted, worn-out, and melting like a paschal candle at the end of the Easter Season, unable to return to the Philippines, Bishop Salazar died on December 4, 1594, with the fragrance of holiness.

Inside the Church of Santo Tomás in Madrid, his tomb bears this solemn inscription: Hic jacet D. Fr. Dominicus de Salazar Ordinis Prædicatorum, Philippinarum Episcopus, doctrina clarus verus religiosæ vitæ sectator, suarum ovium piissimus Pastor, pauperum Pater, et ipse vere pauper.

“Here lies… the most loving Shepherd of his flock, the Father of the poor, himself truly a poor man.”

Jose Mario Bautista Maximiano (facebook.com/josemario.maximiano) is the author of 500 YEARS ROMAN CATHOLIC (2020) and 24 PLUS CONTEMPORARY PEOPLE: God Writing Straight with Twists and Turns (Claretian, 2019).