NEW YORK—As if to underscore the possible ties between the subservience of Malacañang to Beijing, and the horrendous killings due to President Duterte’s barbaric drug-war campaign came two recent developments.

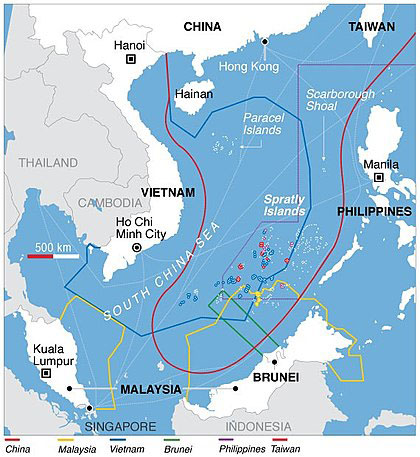

The first had to do with how Filipinos view the increasing encroachment of China over islands well within the Philippines’ coastal waters. According to the latest Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey, ninety-three percent of Filipinos expressed their conviction that it was important for the country to regain control of China-held islands in the West Philippine Sea. Other results from the late June survey: seventy-four percent of the respondents viewed the situation as “very important”; nineteen percent believed it was “somewhat important”; one percent said it was “somewhat not important”; one percent felt it was “not at all important”; and four percent were undecided.

The Duterte administration has responded with surprising but understandable restraint, for it would have been politically unwise for the president to characterize the ninety-three percent as “idiots”—his term for those who have criticized his foreign policy when it comes to China’s bullying maneuvers, the latest instance being the ramming of the Philippine fishing vessel cited in my last column.

Presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo stated at a press conference: “For now, because there is a problem on the claim of ownership, we will resort to diplomatic negotiations.” This is a crack in the previously held what-can-we-do attitude of the government. The question of course is, why only now, when the proverbial horse has been practically stolen from the barn?

The United Nations’ 47-member Human Rights Council in Geneva, to begin an investigation into the thousands of alleged extrajudicial killings in Duterte’s war on drugs. UN PHOTO

It’s precisely the use of diplomacy concomitant with international pressure that has long been advocated in dealing with this sea grab by China—a mighty push given to the Philippine claim in 2016, when the UN tribunal found no legal basis for the Chinese case. Alas, even before exploring how that could be used to the fullest, the supposedly tough, macho Duterte caved in.

The second development was a vote Thursday, July 11, by the United Nations 47-member Human Rights Council in Geneva, to begin an investigation into the thousands of alleged extrajudicial killings in Duterte’s war on drugs. The approved resolution comes at a crucial time: the president has threatened to ramp up the drug war, with even more killings in the final three years of his six-year term.

The Council voted 18-14, with 15 abstentions, approving the Iceland-initiated resolution, calling on the Philippine government to take all steps to prevent extrajudicial killings and charging the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet to prepare a comprehensive report on the Philippines, to be finished in a year’s time. That could set the stage for tougher actions.

Predictably, Malacañang condemned the resolution, characterizing it as Western meddling; Panelo questioned the resolution’s validity, saying only 18 nations in the 47-member U.N. body voted for it.

The former police chief now elected Senator Bato de la Rosa declared that he was ready to be decapitated if the killings were state-sponsored. May I suggest the Quirino grandstand as a venue, should this ever come to pass?

At the same time, an International Criminal Court prosecutor has begun examining these extrajudicial killings to see if a case, of crimes against humanity, can be brought against President Duterte.

Manila has said there have been at least 6,600 people killed since mid-2016, when Duterte took office. A vast majority of the fatalities came from the underclass, suspected (but not convicted) of petty drug crimes. Human rights groups contest that figure, and claim a much higher one, as high as 30,000 deaths.

Nicholas Bequelin of Amnesty International said of the Council’s vote, that it “provides hope for thousands of bereaved families in the Philippines and countless more Filipinos bravely challenging the Duterte administration’s murderous ‘war on drugs.’” At the same time, Amnesty points to Bulacan province immediately to the north of Metropolitan Manila as “the country’s bloodiest killing field” after some officers involved in the crackdown—notably, those originally with the Davao Death Squads—were transferred there from the capital, which used to be the “epicenter of killings.”

Let’s leave the last word to Senator Leila de Lima, one of Duterte’s most vocal critics: “The door of domestic investigation may have been shut, but the windows of international scrutiny are beginning to open up toward justice for the Filipino people.” The senator has been in prison now for two years, on drug charges that she and other human-rights groups say were made up to silence her.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2019