Ex-GI uses DNA tests to help Amerasians find their fathers

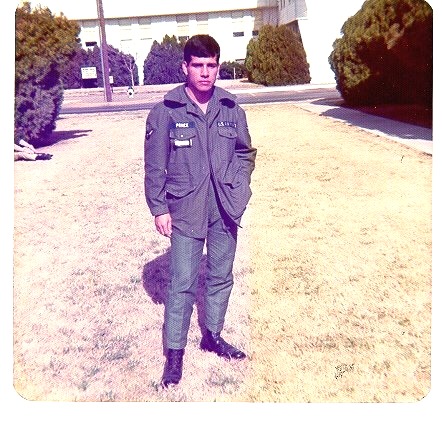

Gene Ponce as a young Air Force officer at Korat Air Base in 1970. CONTRIBUTED

Gene Ponce of California was in the United States Air Force stationed in Thailand from 1970-1972. Now 71, he recalls the day he said goodbye to his Thai girlfriend in 1970 at the main gate of the Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base in Nakhon Ratchasima province.

“She said she was pregnant. I didn’t know what to do. I went back to the U.S. for schooling,” Gene says.

In 1971, while stationed in Ubon Ratchatani Airbase, Gene visited his girlfriend in Korat. Instead of finding her, he saw a baby sleeping in a crib.

Gene Ponce today, with the author. CONTRIBUTED

“My girlfriend wasn’t there. Her parents led me to a backroom and told me that the baby was mine. From that very moment, my life was changed.”

Instead of abandoning the baby, Gene brought his 7-month-old daughter to the United States with help from the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok. The mother chose to stay. They lost communication. Eventually, he found out that the mother passed away five years ago.

In 1998, Gene’s attention was caught by an Amerasian in Denmark looking for her father. He realized the magnitude of forgotten American legacy — the luuk khreung or the Amerasian. After his retirement in 2002, he settled in Thailand until 2017. And his life-long advocacy to reconnect GI fathers and their children began.

Luuk khreung

The Pearl S. Buck Foundation estimates that there are 5,000 to 8,000 Amerasians in Thailand. From 1961 until the last military installation closed on July 20, 1976, American personnel had reached 50,000. Some Thai-Amerasians were able to immigrate to the United States under the 1982 Amerasian Immigration Act, but undetermined numbers are still left in Thailand.

Meaghan Leshana and her biological mother. CONTRIBUTED

Prior to the Vietnam War era, Luuk khreung only meant children with Thai elite lineage, usually a paternal connection. But the involvement of Thailand in the Vietnam War gave a negative connotation to luuk khreung – their mothers were known as “prostitutes.” They were outcasts and orphaned. To be able to assimilate in the Thai society, they were registered under their grandfathers’ or uncles’ names. They have no memories of their fathers except fragments told by their mothers.

Sayan Sanya, a Thai singer popularized the song Mae Pla Ra in the ‘70s deriding an Isan (Northeast Thailand) woman who wants to have a GI boyfriend. (Phla ra is a fermented fish sauce associated with the northeastern food-culture. Almost everything is seasoned with phla ra. Saowanee Alexander, a professor of Sociolinguistics at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchatani University explained that the song reinforced the negative stereotype of Isan women during the Vietnam War.) The Thai man who loves her, warns the GI will eventually dump her. In the end, the Isan woman was left by the GI.

Help me find my father

Thappani Singkamol’s mother went from Chiangmai to Nakhon Ratchasima to look for work. The Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base was opened. Thappani was born on September 9, 1970, to an African-American GI father. As a child, she was called Andy Whait, which could be the name of her father (Andrew Whait).

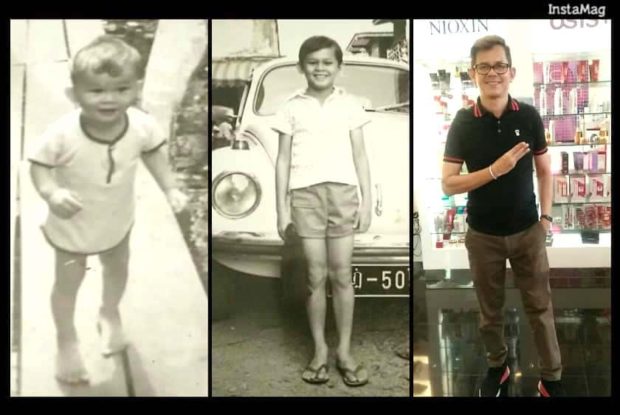

Tanong Pirunproi through the years .CONTRIBUTED

“I did not have friends because I looked different. Mom told me my father wanted to have a son, instead of a daughter, that’s why he left. I just want to know who he is,” Thappani explains.

Connecting to her roots

Born on October 28, 1975, in Ubon Ratchatani, Meaghan Ura Butsringh Leshana was adopted by Juianne Le Shana, an Australian stationed at the airbase and her Canadian husband, Keith. Her parents retained her Thai name, thus her biological mother, Janta Butsing, 70 years old now, was located after 43 years. Meaghan is an Australian citizen.

On January 3, 2019, Meaghan flew to Thailand to meet her mother and the rest of the family.

“As l stepped out of the plane at Ubon Ratchathani airport, l felt nostalgia. l could feel the presence of my ancestors. The runway at the airport was the U.S. army base runway that my biological Afro-American father may had used or stepped foot,” Meaghan shared.

Meaghan found out the circumstances of her birth. She was given up for adoption by her uncle. She doesn’t know whether her mom agreed or not. Janta mentioned Max(w)ell I. Jonson, an airman that could be Meaghan’s father. She had an older sister who died two years ago. The sister was ‘non-existent’ in the village because of her skin color.

Back in Australia, Meaghan is studying Thai language and culture hoping to understand her roots.

Tanong Pirunproi, a hairstylist, wasn’t interested in knowing his father. After all, he was abandoned. He was born in November 27, 1962, a year after the first U. S. Air Force service members arrived at Don Mueang Airbase. He was raised by his mother’s boyfriend after she married a Swiss national. .

“At this point, meeting my father or becoming a U.S. citizen doesn’t make a difference. If I would meet him, I would ask, “Where have you been all this time?” Tanong says.

DNA testing

Gene Ponce was contacted by more than 400 fathers who believed they have children left behind in Thailand. He inquired in hospitals around Bangkok and the former military bases about the children born to American fathers during the Vietnam War.

Thappani Singkamol. CONTRIBUTED

Gene says that the hospitals declared that all records were “destroyed” every 15 years. There is no way to find out the exact figures of the Amerasians born to GIs during the period 1962-1976.

This has not deterred Gene from pursuing the search. He recommends DNA testing to Amerasians to find the nearest relative which in turn could connect to the father.

Gene arrived in Thailand on June 7. Collecting DNA samples were part of the itinerary. He had 12 DNA samples sent to Ancestry.com. The DNA kit costs between $50-100. Gene does not charge anything to those who are seeking his assistance.

At the Mall, Korat, I met Gene and Thappani. He took saliva samples from Thappani.

The laboratory process takes about eight weeks to complete. Each kit has a serial number uploaded to the website upon registering.

“We can view immediate family relatives based on the same DNA. Then we contact immediate family members, 1st-3rd cousins and begin asking them a set of detailed questions pertaining to the Vietnam War and assignments in Southeast Asia (Thailand),” Gene says.

A DNA testing kit. CONTRIBUTED

Aside from Ancestry.com, GEDCOM, also a genealogical software developed by the Church of the Latter-Day Saints, allows all DNA companies to have their DNA results uploaded. This will increase the possibilities of finding more family members.

On June 26, Professor Saowanee informed me that Tanong wanted to have a DNA test. He found out his father’s name is Richard Tiger who was stationed at Don Mueang and probably in the Air Force. On June 28, Gene and Tanong met in Nonthaburi, Bangkok for the DNA collection.

It will take time before the 3 Amerasians find the identities of their fathers. The results will not automatically make them U.S. citizens, but definitely could tie loose ends in their lives.

“I don’t see any effort from the government, I’m doing this to make a difference because it is the right thing to do,” Gene ends.