Artist Jenifer K Wofford explores ‘in-betweenness’

Jenifer K Wofford in front of her ongoing series of works entitled CPV, in honor of her mentor Carlos Pedro Villa. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

SAN FRANCISCO – Jenifer K Wofford’s most recent exhibition at University of San Francisco’s (USF) Thacher Gallery was aptly titled Limning the Liminal—a collection of drawings, paintings as well as artist books spanning 13 years that explore and share a common theme: liminality—a state of being at both sides of a boundary or threshold.

This state of in-betweenness is inescapably the essence of Wofford’s art since it is what she is as a person as well as her life and experience.

“As an artist with my own complicated back story, I’m always relentlessly drawn towards images, stories, or phenomenon that is in a state of in-betweenness because that’s my own identity. I’m not necessarily interested in autobiography in my work, but I feel that I identify with those things elsewhere.”

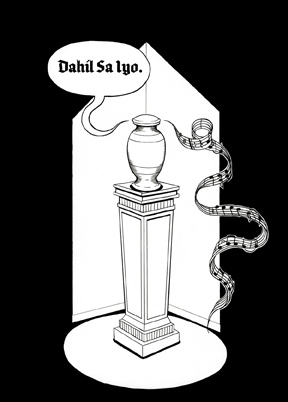

Dahil Sa Iyo from Death Songs, 2019 by Jenifer K Wofford

Wofford is a San Francisco (SF) native with a Filipino mother from Manila and a European American father from Northern California who had met in Thailand. She spent her formative years living in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Dubai with frequent visits to Manila and summer vacations in the Bay Area.

Wofford has been based in the Bay Area since coming back to live here in her teens. “I went to high school in Walnut Creek, did two years of community college in the suburbs, and came out to the city for SFAI.”

Meeting Carlos Villa

It was at the San Francisco Art Institute where she met the celebrated Filipino American artist Carlos Villa; one of a handful of Filipino American visual artists then who was recognized by the mainstream American art scene. Villa became Wofford’s mentor.

Excelsior Fog (detail from Flor 1973-78, 2008_2019) by Jenifer K Wofford

“Carlos opened up this world of thinking about Filipino content in my work, and I didn’t necessarily feel that I have the right to because of the way I grew up. I did not grow up in a deep traditional community at all. But because his practice was so hybrid, intersectional, and the fact that he simply was Filipino American in a space that rarely had Filipino Americans was huge; to just have that role model for me.

“He gave a lot of his students and mentees a different permission to exist in spaces that were not necessarily friendly to them. Carlos’ main ethos was: when you’re an artist, you’re not just a studio based artist, you’re a scholar—you’re informed and you think through it and not just in a little bubble by yourself, you’re an activist, you’re a member of a community. I think that naturally leads to a sort of Filipino community philosophy in terms of interconnectedness, it really all comes from that sensibility.”

I-Hotel (detail from Flor 1973-78 ,2008_2019) by Jenifer K Wofford

Wofford, who is also a professor at USF teaching a course on Filipino American arts, began her inquiry and exploration of the part of her that is Filipino and its implication in her work through other Filipino artists. In the early ‘90’s, she was part of a collective of Filipino American artists called Diwa Arts. Eventually, she formed her own group in collaboration with Reanne Estrada and Eliza Barrios called Mail Order Brides/M.O.B.s

Filipino themes

“Between some of these things and other ideas that that I was exploring in my solo work, I felt that Filipino themes were a very natural way for me to work through imagery. But, you know, its come and gone, and it doesn’t come up in every single project.”

Wofford describes her art as interdisciplinary. Her work is rooted in drawing and painting but is comprised of various media as informed by each project.

I Hotel Protest (detail from Flor 1973-78, 2008_2019) by Jenifer K Wofford

“Every project varies, and the idea determines the medium I end up using. For some of the work in this particular exhibition, it felt like the right strategy to work in a pictorial way whereas other projects are video, performance, photo, sculpture, and installation.”

After finishing a degree at SFAI, Wofford went on to pursue a master’s degree at UC Berkeley where came at a crisis point for her and her art.

“I found myself in a space that felt really homogenous, pretty white, and I felt that I was at a crisis point as to how to contend with making the different kinds of imagery for the world.”

She then took a class with UC Berkeley professor and author Catherine Ceniza Choy in Filipino Narratives. It became another pivotal point in her life and career.

Lola Cristeta from the Lolas series, 2018 by Jenifer K Wofford

“That class was really inspiring for me. And Cathy’s scholarship on nurses in particular, her book Empire of Care inspired me, of course, because I have a Filipino nurse mom. That’s really where the point of connection came.”

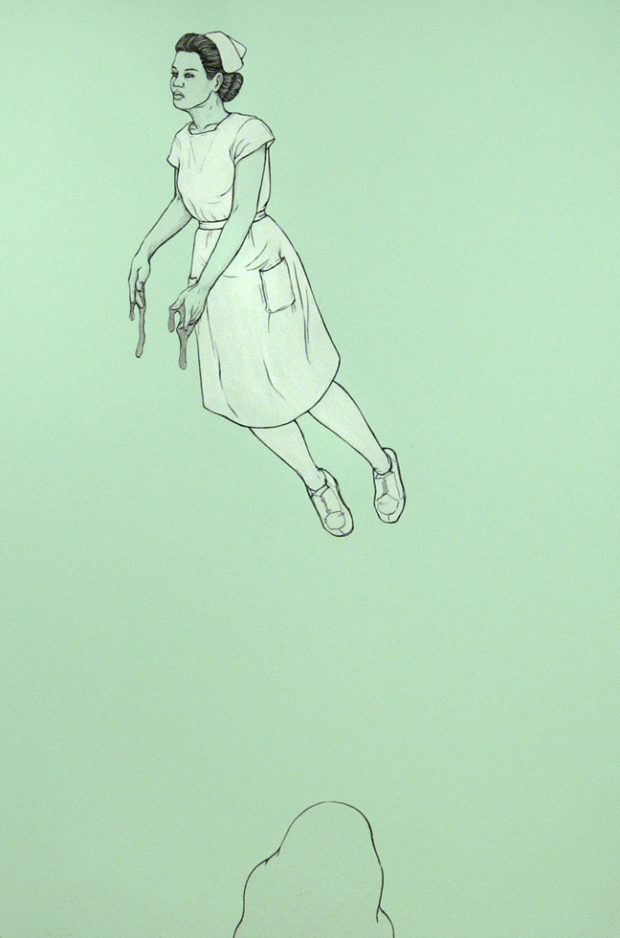

Limning the Liminal, that ran from February 25 to April 14, 2019, featured drawings by Wofford from as early as 2006 known as the Nurse series in which Wofford “presents images of Filipina nurses enveloped in an abstract and institutional green ‘goo’ that functions as both flesh and border, asking viewers to consider the ways in which these essential caregivers are made invisible.”

Figurative and the abstract

“What I really love about her work is when she’s combining that narrative or figurative with the abstract—that nurse series had the two together. It allows her mystery and allows for the viewer to bring what they want to the pieces. I have a nurse in my family, so I could empathize with that,” says Thacher Gallery Director, Glori Simmons.

Looking Up Kearny Street (detail from Flor 1973-78, 2008_2019) by Jenifer K Wofford

Other works that were featured in this exhibition are the Lolas series (2016), “portraits of some of the longest-living lolas and comfort women who as girls were enslaved and brutally raped by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II;” Flor 1973-1978 (2008), a series of public art posters commissioned by the SF Arts Commission as part of their Market Street Art in Transit Project that “imagines six years in the life of a fictional immigrant from Manila, Flor Villanueva, situating her in a variety of settings and historic events in both San Francisco and Manila in the 1970’s;” Collapse (2015-2019, ongoing), a series of acrylic paintings “functioning as a metaphor for broader contemporary conditions of cognitive and cultural collapse, this suite of paintings renders the aftermath of seismic ruptures around the Pacific Rim;” and Death Songs (2018), a series of drawings and an artist book that imagine the dead submitting their final song requests.

“We all accumulate grief and loss in our lives, and so I’d written a grant to do a project on people’s death music. Basically, when you die, what would you like played at your funeral?”

“A great liminal space between life and death. This is my inappropriate way of dealing with it.”

Also part of the exhibition is an ongoing series of painting, drawings and small studies entitled CPV that she started in 2013 to honor her mentor Carlos Pedro Villa who passed away that year.

Riser Nurse from the Nurse series, 2006 by Jenifer K Wofford

“The gallery’s mission is to bring art, scholarships, and the community together. I think this show does that really well,” says Simmons. “The works definitely have clear intentions, but I also feel that they are open for us to bring what we have to the pieces. I love that balance .All of her work dealt with liminal spaces and liminal identities and experiences. We touch on so many different aspects of liminality, from immigration experience to being invisible to history, to death.”

As with her ongoing work of earthquake paintings, Collapse, Wofford, who happens to have a fixation with earthquakes, is creating more works around the same theme. She will be creating and exhibiting works for the 30th anniversary of the Loma Prieta earthquake that happens later this year. One of these will be an exhibition at Black and White Projects in SF from September 20 to October 26, 2019 that she describes as “an immersive installation with a lot of images related to that era. It will be built like a late ‘80’s dance club, but with drawings of earthquake stuff.”

In relation to the Loma Prieta earthquake anniversary, Wofford is also going to exhibit prints from an ongoing web project called Earthquake Weather as part of a biennial exhibition marking the 30th year since the global, cultural, and political upheavals of 1989 entitled Present Tense 2019: task of Remembrance at the Chinese Culture Center of SF from April 27 to December 21, 2019.

Unlike the majority of Filipino Americans who grew up in a social system that is highly racialized, in which one is forced from the get go to try to assimilate and identify one way or the other, Wofford had a radically different experience growing up as a mixed-race person of Filipina and European American descent that is distinct from her counterparts in the Filipino diaspora in the US as well as the Philippines.

“Unlike a lot of my Fil-Am friends who grew up really isolated from their culture and having a different kind of yearning, I just quite didn’t have that feeling.”

But despite all the different circumstances that makes for our unique experiences, a common feeling that binds all Filipinos, that could also be said of all postcolonial people who, along with their fragmented histories continue to face the challenge of how to be in this world, is that state and feeling of in-betweenness, of not quite belonging anywhere, of liminality. It is in these liminal spaces that Wofford not only thrives but also knows the only way to be and make sense of the world around her.

“I don’t understand the world in any other way.”

The big shift

The “big shift” in her way of seeing the differences between her and other Filipinos, and how this could be an enriching part of her life and identity, happened when she went to the Philippines in 1998. It was for an exhibition at the Museo ng Maynila called Sister City Sisters (SF and Manila being sister cities).

Sinking Nurse from the Nurse series, 2006 by Jenifer K Wofford

“I met a bunch of local Filipino artists, and all of a sudden I felt ‘my people, my people in Manila.’ It really hit me hard because I grew up without a lot of traditional attachments. And pretty much from that point on I just kept showing up year after year just to hang out with folks and built a number of friendships that way.”

Finding comfort and grounding in the liminal and having liminality as away being and an essence of her art, Wofford shuns mainstream notions of identity and the constant need to identify.

“I didn’t grow up with a particularly monolithic, fixed, centralized identity. I’m always going to gravitate towards things that are liminal or hybrid. I think that is my grounding. I actually get a little claustrophobic, I feel constricted, when somebody tells me, ‘You know this is how it’s supposed to be,’ and I’m like ‘The world isn’t that fixed friends.’ I tend to get a little shifty around that stuff.”

“I’m not afraid of identity, but there were too many times, especially when I was younger, when people were very insistent that you be this or you be that. And I was never about that. That made no sense to me… Are you Filipino or are you white? Are you American or are you Filipino? Those kinds of questions are pointless to me.”

“The only place that I ever feel that I wished I belonged more is that I don’t speak Tagalog. I could’ve learned it at this point, but part of the challenge of going to a place like Manila is that everybody speaks better English than I do. It’s a constant battle of folks just being, ‘Don’t worry about it, don’t even learn,’ but two seconds later, ‘Ay talaga (Oh really)? You still don’t speak Tagalog?’ That’s the only place where I feel a certain kind of hiya (shame).”