Why the ICC case against Duterte is legally flawed

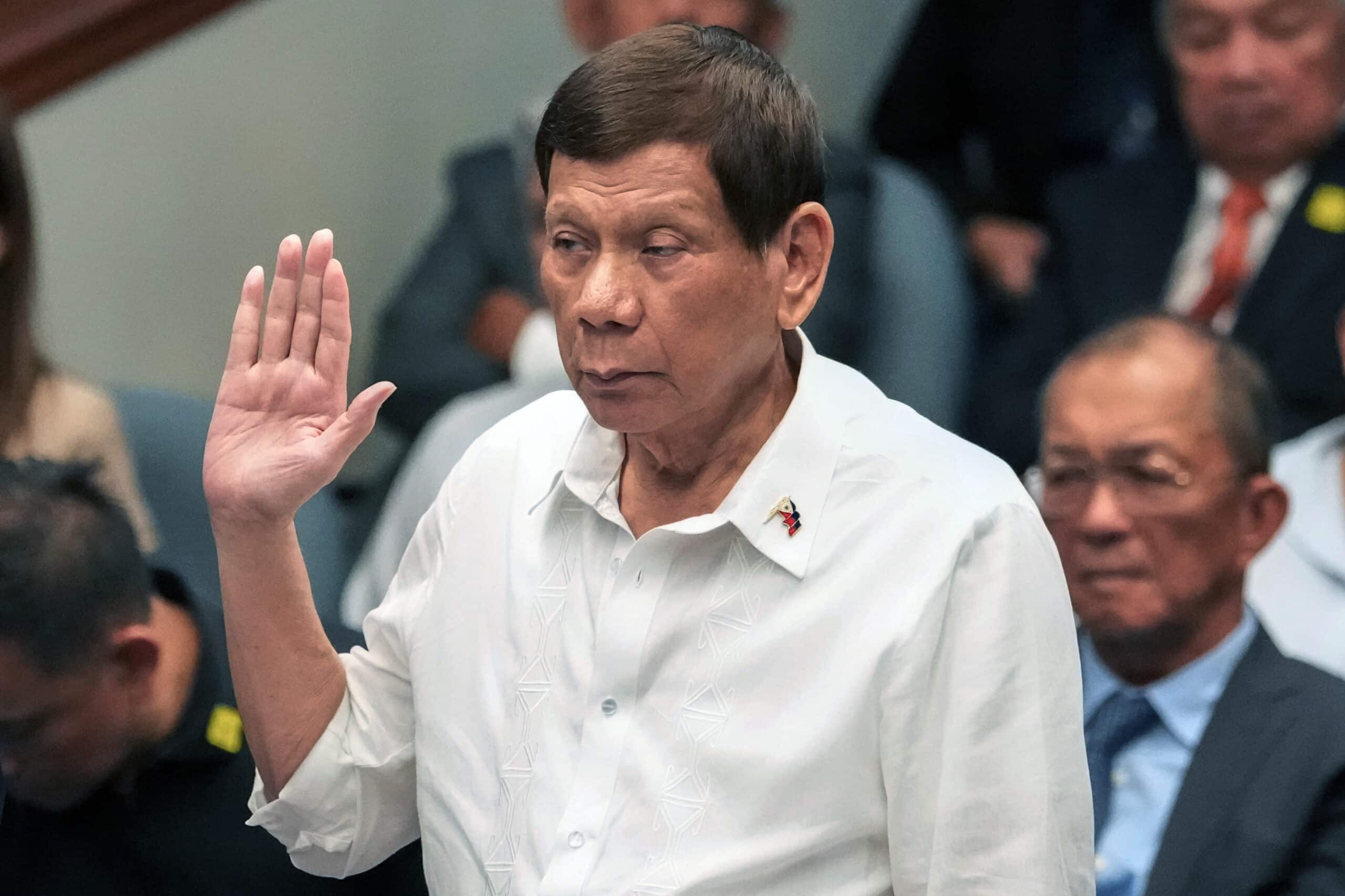

FILE – Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte takes oath during a senate inquiry on the so-called war on drugs during his administration at the Philippine Senate, on Oct. 28, 2024, in Manila, Philippines. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has never prosecuted an anti-drug campaign as a crime against humanity, and attempting to do so now raises serious legal and jurisdictional concerns.

More importantly, the global war on drugs has already been acknowledged as a failure by the very institutions that once championed it.

After more than 63 years, even the United Nations (UN) has admitted that its international campaign against illegal drugs has not succeeded. Instead of curbing the drug trade, decades of prohibitionist policies have fueled mass incarceration and escalated violence, and created black markets controlled by powerful cartels.

Now, in a drastic shift, the UN is proposing dangerous alternatives – legalization and decriminalization of illegal drugs – without addressing the root causes of the drug epidemic.

Similarly, the United States’ own war on drugs, spanning more than three decades and costing trillions of dollars, has failed to eliminate the drug problem. The policies of prohibition, particularly in Latin America and within the US, have led to the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives, including innocent civilians caught in cartel violence.

Despite these enormous efforts and expenditures, drug addiction rates remain alarmingly high, and illicit drug trafficking continues to thrive.

Crimes against humanity: The legal standard

Under Article 7(1) of the Rome Statute, crimes against humanity require:

- A widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population

- A state or organizational policy directing the attack

- Acts such as murder, extermination, torture or other inhumane acts

These elements must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. However, a closer examination of the Philippine case reveals why it fails to meet this legal standard.

The Philippine drug war lacks the characteristics of crimes against humanity

1. No widespread or systematic attack on civilians

Crimes against humanity cases before the ICC have typically involved genocide, war crimes or ethnic persecution – such as the Darfur Genocide (Prosecutor v. Al Bashir) or the Rwandan Genocide (Prosecutor v. Akayesu).

By contrast, the Philippine anti-drug campaign was a law enforcement operation targeting criminal drug networks. The deaths reported in drug operations often resulted from armed resistance by suspects, legitimate self-defense by police or extrajudicial killings that were not sanctioned by state policy.

Furthermore, Duterte’s drug war is not unique in its intensity or tactics. Countries such as Mexico (120,000 deaths under President Felipe Calderón’s drug war), Colombia’s decades-long counter-narcotics campaigns and Thailand’s violent drug war under Thaksin Shinawatra all faced allegations of mass human rights violations. Yet, the ICC declined to prosecute these cases, recognizing that drug enforcement remains within the domain of state sovereignty. Treating Duterte’s campaign differently raises concerns of selective justice.

2. Law enforcement, not crimes against humanity

The United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (1988) obligates states to adopt strict measures against drug trafficking. The Philippines’ Oplan Tokhang was not a campaign of extermination but a police initiative to neutralize drug syndicates.

While some police officers may have engaged in abuses, individual cases of misconduct should be prosecuted under domestic law – not through an ICC case against a former head of state.

The principle of complementarity under Article 17 of the Rome Statute dictates that ICC intervention is only warranted if a country is “unwilling or unable” to prosecute crimes. This does not apply to the Philippines, which has:

- Convicted police officers for extrajudicial killings (e.g., the Kian delos Santos case)

- Investigated and prosecuted rogue law enforcement officials

Since Philippine courts remain functional, ICC jurisdiction is both unnecessary and an overreach.

The global drug war’s failure: Why the ICC must reconsider

The case against Duterte must also be viewed in the context of the wider global drug war failure.

- The UN’s admission of failure: After over 63 years of aggressive anti-drug policies, the UN now acknowledges that prohibition has failed and is proposing decriminalization and legalization as an alternative.

- The US drug aar: A trillion-dollar failure: The United States has spent over $1 trillion on the war on drugs since the 1980s, yet overdose deaths continue to rise, with more than 106,000 drug-related deaths recorded in 2021 alone (CDC).

- Latin America’s narco-terror crisis: Countries like Mexico, Colombia and Brazil remain overrun by drug cartels, despite decades of military-led crackdowns.

Given this undeniable global failure, why should Duterte’s approach to the drug crisis be singled out for prosecution? The ICC risks losing credibility by selectively targeting the Philippines while ignoring the far deadlier drug wars waged by Western nations and their allies.

Selective persecution: Why Duterte?

The ICC’s decision to pursue former President Duterte while ignoring other global leaders with far more egregious crimes underscores its glaring bias and selective prosecution.

Russian President Vladimir Putin faces an outstanding ICC arrest warrant for alleged war crimes in Ukraine, yet he travels freely to allied nations. George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush orchestrated military campaigns that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands in Iraq and Afghanistan, yet the ICC never indicted them. Benjamin Netanyahu‘s ongoing military actions in Gaza have resulted in mass civilian casualties, but he has faced no ICC action.

Even former Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir, who was charged with genocide, managed to avoid arrest for over a decade despite numerous ICC warrants.

The ICC’s refusal to act on these cases while singling out Duterte – whose alleged crimes do not even fall under the traditional scope of crimes against humanity – exposes its lack of impartiality and raises concerns that the Court is being weaponized for political motives.

Conclusion: The ICC should dismiss the case against Duterte

The attempt to prosecute Duterte for crimes against humanity is legally unfounded and unprecedented. The case should be dismissed because:

- The anti-drug campaign targeted criminal syndicates, not a civilian population.

- There is no state policy of extermination – isolated abuses do not equate to systematic crimes.

- No previous ICC case has treated a government’s anti-drug operations as a crime against humanity.

- The Philippines has a functioning judicial system, negating the need for ICC intervention.

More broadly, prosecuting Duterte while ignoring the well-documented failures of the global drug war is both hypocritical and legally inconsistent.

The ICC should not allow itself to be weaponized for political agendas, nor should it undermine sovereign nations’ rights to enforce their laws against criminal drug networks.

In light of the UN’s admission of failure, the continued drug epidemic in the US, and the persistent cartel violence in Latin America, the ICC must reconsider its priorities.

The real question is not whether Duterte’s drug war was perfect – but whether the global community is finally ready to confront the failure of prohibitionist policies and pursue solutions that actually work.

Atty. Arnedo S. Valera is the executive director of the Global Migrant Heritage Foundation and managing attorney at Valera & Associates, a US immigration and anti-discrimination law firm for over 32 years. He holds a master’s degree in International Affairs and International Law and Human Rights from Columbia University and was trained at the International Institute of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. He obtained his Bachelor of Laws from Ateneo de Manila University.