This was intended to be a light column. But it’s hard when you consider journalism is one of the world’s most dangerous jobs.

The price of truth, right?

So, we pause to pay our respects to Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi, an American permanent resident who wrote columns for the Washington Post. He was last seen entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul last week, and wasn’t seen from again. His fiancée, a Turkish woman was waiting for him outside but Khashoggi never emerged.

The Turkish government now reportedly says they have video and audio evidence that Khashoggi was murdered inside the consulate.

What will the Trump administration do?

The Saudis spent under $10 million in lobbying operations in the U.S. in 2016, and that number tripled in 2017 to $27.3 million, according to reports. The money is used to ensure the continued flow of U.S. arms sales and military spending to the Saudis.

So, when Donald Trump says, “What happened is a terrible thing, assuming that happened,” we can’t be sure what response the U.S. will have.

Will the U.S. care about human rights and sanction Saudi Arabia? Or will Trump’s hesitation show he only values dollars over common sense?

This is the problem when the president has the moral compass of a bean counter. Human compassion, concern, empathy lose out. It’s profits over people. And you can get bet other nations are watching. A critic of the Saudi government is reportedly murdered in the Saudi Embassy, and the U.S. is doing nothing?

Well, then, anything goes. Score another point for the fascists.

The world continues to worsen with every Trump move.

Kashoggi had been critical of the Saudi government in his writings. But was in Turkey to get documents to allow his impending marriage. The mysteriousness of his disappearance should give pause to all, and make us all realize journalists’ work still packs a wallop.

The press is not the enemy of the people. It wields real power and influence. Maybe too much. Enough to make the brazen silence an ethnic journalist like Khashoggi and take his life.

Importance of the ethnic press

It’s the first draft of history, as they say. Once the 15th passes, the confluence of National Hispanic Heritage Month and Filipino American History Month ends, and the Filipinos have October all to themselves.

Or so I thought.

October turns out to be a little promiscuous. It’s also German American Heritage Month (Oh, yeah that Octoberfest thing). LGBT History Month, and it’s Polish American Heritage Month (Hot dog!)

And why stop there? Since there are only 12 months, can you blame breast cancer, dyslexia, anti-bully, anti-vaccine, orthodontists, and even pit bulls from wanting a piece of October? Why not, the more the merrier. It’s also ADHD Awareness month.

The ultimate October parade just might be one with a trans breast-cancer survivor, who was bullied and suffered a vaccine injury, but who had a really great smile with straight teeth and good dental hygiene, proudly marching their (gender neutral) pitbull as they patrol the neighborhood. (Didn’t you know? it’s National Crime Prevention Month.) That could be the look of the best overall October poster child, if they were at least half Filipino with a Spanish surname, with another parent of German/ Polish descent.

And to top it off, let’s sit down to a meal of that Chinatown specialty, roast pork, Filipino lechon. What do you know–it’s National Cholesterol Month.

Ah, Diversity! But let’s keep it simple, shall we. We’re Asian Americans.

From now until the end of Halloween, Filipinos are the pumpkin spice of the tribe.

Literally, we’re the Asian American flavor of the month.

And the month started off with a bang when I won a Plaridel Award for best commentary for a column on the first Filipinos to America that appeared on this blog and in the Philippine ethnic media.

I did more serious columns in the last year about Trump and Duterte. But of all my columns, this one engaged the most readers.

Plaridel is the pen name for one Marcelo H. del Pilar, billed as a writer/journalist above lawyer, and known as a Philippine national hero–the father of Filipino journalism–for his passionate writings railing out against the Catholic Church and colonial Spain.

Of course, he wrote in a small publication and died a pauper. What an example for the modern ethnic journalist who writes the first draft of history for the community.

For this amok columnist, it was an honor to receive the award. And another for Best Radio/Podcast for an interview on the Congressional Gold Medal for Filipino vets of WWII. A third column won a merit award, but it was the top entry in the Personal Story category. I wrote about how men can be sexually harassed by women in the workplace. Don’t think it’s not a two-way street.

So all of this, to kick off the month, and so close to my birthday, on the self-canceling Leif Ericsson Day, the day Scandinavians celebrate immigration to the U.S.!

Filipinos Were Here First

The subject of that award-winning column is one of the reasons October is Filipino History Month. Filipinos were actually first to step foot on America, Oct. 18, 1587.

That’s 33 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. And they get a holiday. And yes, it was nearly 100 years AFTER Columbus, but he was somewhere in the Bahamas. Not in California like the Filipinos.

The Filipino American National Historical Society picked October as its month based on the scholarship of Eloisa Gomez Borah, a librarian who published her analysis of explorer Pedro de Unamuno’s logs in UCLA’s Amerasia Journal.

Her article details how Unamuno, sailing for Spain, had at least eight Filipino crew members. It was the Filipinos who led the landing party off the central coast of California in what is now Morro Bay.

Of course, the help never gets any of the glory. And the land was taken for the Spanish. But the Filipinos technically were the first non-indigenous people to step foot on the continental U.S.

Being fodder comes with some privilege. Any sliver of mention are points of pride and worth savoring in a whitewashed mainstream history.

But the day after I got my award, I had lunch with Alex Fabros, a former FANHS trustee and San Francisco State Asian American historian, who has long taken issue with the accuracy of Morro Bay.

Unamuno’s landing is solid. The diaries back the dates. But where did he land?

My column didn’t question that. But Alex Fabros, 72, set me straight.

Fabros is somewhat of an American Filipino renaissance man. He’s a retired military officer, as well as a sailor, and in 2001, he took a boat load of the historically curious off the Pacific coast with the hopes of replicating Unamuno’s voyage.

That’s when Fabros noticed something fishy.’

NSC WEBSITE

“Unamuno talks about having to avoid some islands and then he comes inland,” Fabros told me. “There are only two places on the California coast that meet that criteria–one is San Francisco, which has the Farallon Islands, the other is Santa Barbara. But if he’s sailing south, it’s the Farallons, and chances are it could be Half Moon Bay.”

As he replicated Unamuno’s galleon sail, Fabros was armed with an astrolabe and a sextant in 2001, and noticed that he could be 100 miles off. With the island reference and the error factor, Fabros is almost certain that Unamuno landed in Half Moon Bay, about a three-and-a-half hour drive north of Morro Bay on U.S. 101.

Borah mentioned the “crab mentality” of others and stands by her interpretation.

But Fabros is no crab. He’s a former adjunct Asian American history professor, who happens to be a decorated veteran, exposed to Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. He’s not interested in a fight. Just the truth. He simply says his replication of Unamuno’s journey shows Morro Bay is just the wrong place for history.

Postcards from Salinas

Fabros’ challenge goes beyond the first Filipinos. He’ll say unabashedly that it was the Salinas Valley, Steinbeck Country, just north of Monterey, where the Filipinos really fought the violence of discrimination and racism in America. Much more so than Stockton or San Francisco.

The Stockton Filipinos were mostly migrants, Fabros said. Hence, the labor contracts would come and go. In Salinas, the workers stayed, so labor contracts were usually hard fought victories that resulted in stronger more lasting contracts, Fabros said.

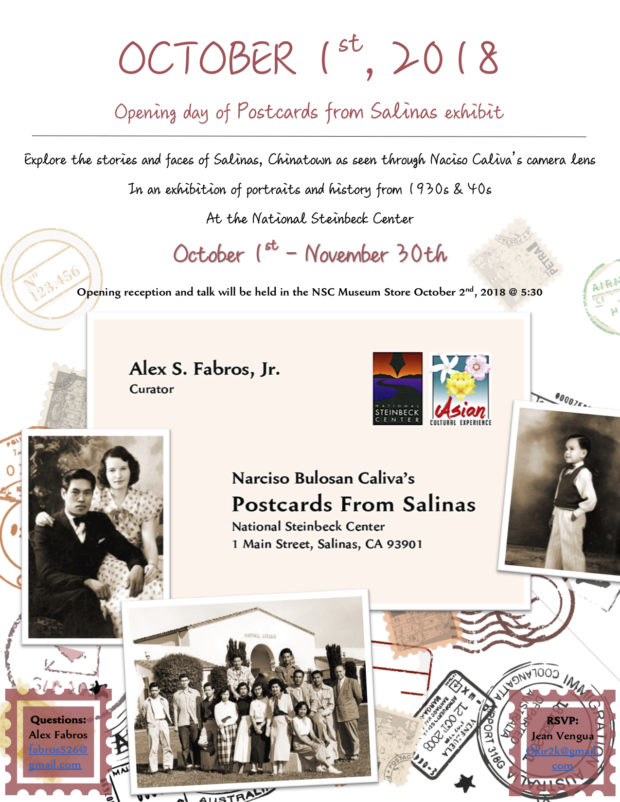

Fabros tells the story of the Central Coast Filipinos in a new curated exhibit, “Postcards from Salinas,” at the National Steinbeck Center’s art and culture gallery.

You’ll see the sepia toned photographs Filipinos sent home during the 1920s and ’30s to let the family know all was well in America.

Meanwhile, Filipinos were being violently harassed for consorting with and marrying white women. It led to anti-intermarriage laws that were the emotional subtext of the day.

Fabros uses the Caliva family photos in the exhibit. Narciso was a cousin of the legendary Filipino writer Carlos Bulosan.

Caliva is seen with his wife, Lucy, in a key photograph. Just the sight of a Filipino man and a white woman was enough to justify rage and anger among white men at the time.

Love meant courage.

Filipinos stood their ground.

If you don’t know Filipino American history, the postcard exhibit in Salinas is a great primer. The evocative photographs are as comprehensive a look at Filipino American life from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Along with the FANHS National Museum in Stockton, they’re both worth a visit to Northern California, especially during October, Filipino American History Month.

It will show you there’s more than enough material in the past and present for journalists and historians to mine.

Too much has been left unsaid, and untold when it comes to Filipinos in America.

Emil Guillermo is a journalist and commentator, and a columnist for the Inquirer’s North American bureau. Listen to him on Apple Podcasts. Twitter@emilamok