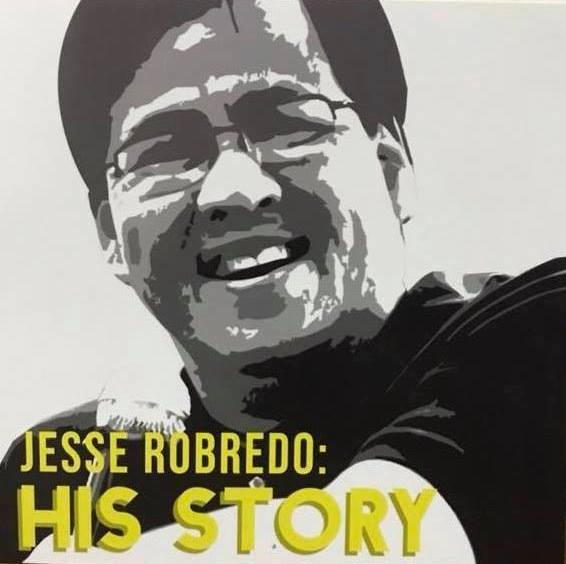

A painting of the late Jesse Robredo in the Museo ni Jesse Robredo. CONTRIBUTED

In 2000, Jesse Robredo received the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award for good governancefor his “sheer dedication, untarnished reputation, and visionary leadership as the 3-term Mayor of Naga City.”

In 2017, Rodrigo Duterte was named Man of the Year by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, tagged as the “individual who has done the most in the world to advance organized criminal activity and corruption.”

It’s not surprising that Naga, the city once led by a mayor who, according to the Ramon Magsaysay Award citation, gave “credence to the promise of democracy by demonstrating that effective city management is compatible with yielding power to the people,” has been denounced by a president who, the Organized Crime and Corruption Project said, “empowered a bully-run system of survival of the fiercest” making the Philippines “more corrupt, more cruel, and less democratic.”

It’s not just because another Nagueño Vice President Leni Robredo, Jesse Robredo’s widow, has emerged as a credible alternative to a president who has also inspired mass slaughter.

Naga, in many ways, is a reminder of the type of leadership style that Duterte and his allies would reject and find threatening.

Jesse Robredo was in the process of taking his “matino at mahusay” leadership philosophy to the national level when he died in a plane crash in 2012. It was a devastating blow to the nation.

Finally, Filipinos, especially the youth, can learn more about Jesse Robredo’s uplifting story in a newly published biography.

Jesse Robredo: His Story, by award-winning novelist and journalist Criselda Yabes, traces one of the most inspiring political journeys in recent Philippine history.

This is the story of the Filipino leader who made “decency and brilliance” the cornerstone of his political career. Jesse Robredo spelled this out in his most famous quote: “Hindi na sapat na tayo ay matino lamang. Hindi rin sapat na tayo ay mahusay lamang. Hindi lahat ng matino ay mahusay, at lalo namang hindi lahat ng mahusay ay matino. Ang dapat ay matino at mahusay.”

(“It is not enough to be decent. And it is also not enough to be brilliant. Not everyone who is decent is brilliant, and not everyone who is brilliant is decent. You have to be both decent and brilliant.”)

The cover of Jesse Robredo: His Story, by award-winning novelist and journalist Criselda Yabes. CONTRIBUTED

In Cris Yabes’ absorbing account of Jesse Robredo’s story, we meet the person who had the greatest influence on his life: his father, Jose Robredo. He was blind.

“Jose Robredo did not dwell on his handicap,” Yabes writes. “He turned his misfortune around and made it a rod of his strength. Without his sight, he used his ears to listen to radio news for the daily fill of politics, he made the children read instruction manuals to him.”

The Robredos were a well-connected family in Bicol. Jose Robredo was “a confidante to Luis Villafuerte,” the powerful governor of Camarines Sur who was Jesse Robredo’s uncle. In fact, that connection helped Jesse Robredo in his first successful campaign for Naga City mayor.

Eventually, a dispute over jueteng led to his break with Villafuerte.

“Jesse wanted it out of the city,” Yabes writes. “No sooner had he sat in office than the controversy broke out. Jesse fired the chief of police whom he discovered to be protecting the jueteng operations. The chief of police, as it turned out, was Luis Villafuerte’s appointed man. The governor didn’t like that. The conflict ruptured bloodlines.”

In the book, Yabes cites a Robredo cousin, Vic Hao Chin, who “saw that Jesse’s moral ground stood on the principles of his blind father …The old man’s mooring between what is right and what is wrong was unshakeable. He simply expected the same of his own. Vic recalled that apart from the jueteng scandal, the fissure began with a small thing when one of the Villafuerte kin wanted to use a government-owned jeep from City Hall for private purposes. Jesse refused, he was clear about any abuse of authority. He especially didn’t want family to be seen taking advantage of his position.”

Robredo overcame repeated attempts to discredit and dislodge him from Naga City Hall. Meanwhile, he worked with diverse forces and organizations, including opposition groups, in transforming Naga from what the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation called “a dispirited provincial town” into an internationally recognized success story. In 1999, Naga was named Asia’s most improved city by Asiaweek.

Jesse Robredo’s success in Naga City propelled him to the national stage. His achievements in Naga also underscored a core principle of his leadership style: work within the system, but have the guts to challenge the corrupt power-wielders who stand in the way of making the system more responsive to the needs of the people he vowed to serve.

One aspect of this biography is unfortunate and disappointing: the cover, which features a smiling Jesse Robredo with text in yellow. The yellow theme was apparently meant to highlight Jesse Robredo’s high profile role in the administration of Noynoy Aquino.

But that’s only a small part of Robredo’s political story. In fact, Pnoy didn’t always get along with Jesse Robredo, who led his 2010 presidential campaign. Jesse Robredo was a tireless, hardworking campaigner. Unfortunately, his candidate didn’t have the stamina to keep up. In fact, PNoy bore a grudge against Jesse Robredo for the way he organized the successful campaign.

“The campaign period was too extreme and arduous for Noynoy; since there was a sudden twist in the political events, he had to cover as much groundwork as he could,” Yabes writes. “Noynoy couldn’t take the fatigue and mental black outs from having three hours sleep, eating a Jollibee sandwich that constituted breakfast and lunch while on the go, and a late dinner of bulalo broth with some rice. ‘These people worked with my mom,’ he said, ‘parang I was being ordered around.’”

Noynoy Aquino’s resentment toward Jesse Robredo lingered even after he won the presidency. That bitterness came into play when Robredo was being considered for a cabinet position.

Noynoy’s running mate, Mar Roxas, had to step in to advocate for Jesse, Yabes writes: “Noynoy could just not forget it, a trait of harboring a long memory that he must have inherited from his mother. ‘You know,’ Mar offered his opinion to Noynoy, ‘it’s not against you as a person, he was just so enthusiastic.’”

Aquino eventually agreed to let Jesse Robredo join his cabinet — but with a catch. Jesse would be appointed Secretary of the Department of Local Government. But his role would be limited to “administration of the local government units.” He would not have anything to do with security matters, or “the police side of it,” Yabes writes.

That part of the job would go to an undersecretary, Rico Puno. He was PNoy’s close friend and kabarilan, his shooting buddy.

Again, it was Roxas who stepped into to convince Jesse Robredo to accept the offer: “Mar told Jesse to take it, ‘Pare, whatever it may look, whatever it may feel … whatever it will be, just stay and keep it.’”

Jesse Robredo did and he quickly found himself in a bind due to his limited role. In August 2010, shortly after PNoy’s presidency began, a disgruntled police officer took over a tour bus at the Rizal Park. A bungled rescue operation led to the deaths of eight tourists and an international scandal.

Yabes writes: “Even though Jesse was not involved in the police operation of his department, he nonetheless took responsibility as head of the DILG. He wanted to be at the scene but he was prevented from going; it was much later in the evening when he went there to assess the situation with his two young staff members.”

“Jesse was kept out of the Luneta operations but he took up the cudgels, ready to resign if he had to. His hands were tied.”

The Luneta tragedy set the tone for what turned out to be a short but challenging stint as DILG secretary. It also set the tone for the PNoy years, which came to be known as a time when the country was led by a president whose loyalty to his closest friends at times led to disastrous decisions.

Author Criselda Yabes (right) at the monument to Jesse Robredo. CONTRIBUTED

Thanks to Cris Yabes’ biography we get a more complete picture of Jesse Robredo’s record, which clearly went beyond the hacendero-style politics of the president he served as cabinet secretary before he died.

Jesse Robredo: His Storyrecalls the journey of the hardest working public servant of his time, the political visionary who learned to navigate a corrupt, inefficient political culture and found creative ways to work with forces of different stripes and colors.

Sadly, we never got a chance to see how his “matino at mahusay” leadership philosophy would have evolved or perhaps even set a more upbeat and constructive tone especially in the turbulent closing years of Noynoy Aquino’s presidency.

Still, the Robredo “matino at mahusay” philosophy is a powerful counterpoint to the current “balahura” leadership style embraced by Duterte and his allies, boosted by the Marcoses who seek to restore an authoritarian order.

Even more important is this: the tale of how Jesse Robredo rallied an entire city to effect dramatic changes in Naga City is a compelling reminder of what needs to be done in order to resist the return of fascism in the Philippines.

Cris Yabes sent me a photo of a painting of Jesse Robredo which hangs at the Museo Ni Jesse Robredoin Naga City. The colorful portrait is a more accurate representation of Jesse Robredo’s life story.

“This is the cover I would have wanted,” she told me. “You see it as you enter the museum. This was done by an artist from Naga. Jesse was a rainbow man. He was open to everybody, including those who were in the opposition.”

For more information on Jesse Robredo: His Story, send an email to partnershp.jmrf@gmail.comor visit the Jesse Robredo Foundation site.

Follow the Kuwento page on Facebook.