Amerasian in Olongapo needs help for dialysis

Pinky Date Yabut having dialysis in Olongapo on July 23. CONTRIBUTED

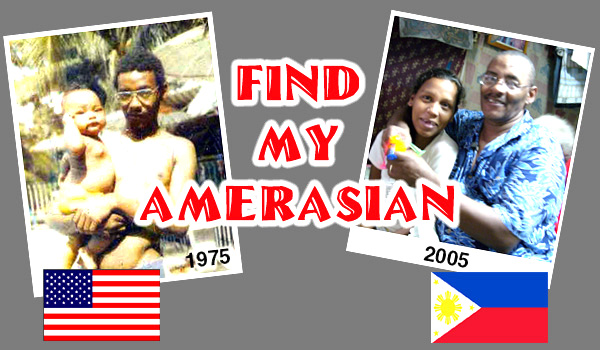

Jimmy Edwards, 66 years old of North Carolina, was among the hundreds of former U.S. servicemen looking for children had they left behind in the Southeast Asia. With over 200,000 Amerasians in the Philippines, many of whom have no birth certificates, only photos and mementos, it is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Edwards did not intend to leave behind his girlfriend, a certain “Merlie Asis/Francisco,” and his baby, Pinky, who was born on March 27, 1975 in Olongapo City.

I was on a repair ship that visited Subic and we were there for long periods of time. My brother was stationed there and he introduced me to Pinky’s mother. I put in a request chit to marry her before she even got pregnant, but it was denied. I told her when we returned in nine months I was going to marry her illegally out in town,” Edwards says.

Edwards claims that he was in touch with Merlie until 1978. The last photo he had with his daughter was taken at White Rock Beach in Subic. Pinky was only seven months old when he last saw her.

Finding Pinky

Edwards says that Merlie had married another sailor, thinking that he would not come back. Naturally, the husband did not want Edwards to continue communicating with Merlie.

Father and daughter reunion. CONTRIBUTED

“Her husband sued me to keep me from having contact with her mother and giving her money for Pinky. I still gave money through one of her mother’s friends,” Edwards recalls.

When the letters stopped coming, Edwards started looking for Pinky in 1980. He contacted Pearl S. Buck Foundation and some Catholic groups to no avail. However, on March 28, 2005, just when Pinky turned 30 years old, Edwards got an email from the coordinator of USA Bound Inc., telling him that Pinky Daet Yabut has been found living in poverty in Olongapo. Pinky has also a kidney problem and is undergoing dialysis.

That same year, a German filmmaker heard about the Edwards and decided to do a documentary on Amerasians. Edwards was sponsored a trip to the Philippines to be reunited with his daughter and to meet his grandchildren.

Meeting Pinky made him realize the extent of the “left behind” children of the GIs. He started a website (www.amerasianregistry.yolasite.com/) to help other parents reunite with their children. Edwards was able to locate over 200 fathers and some of them were able to visit their offspring. He also started sending petitions to Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump to change the laws and allow Amerasians to be U.S. citizens.

A dark-skinned Woman in the Philippines

Pinky is the oldest among seven siblings from different fathers. Only one is Filipino, the rest are African Americans.

If a Caucasian Amerasian found things difficult growing up, it was worse for the blacks.

“My classmates and relatives taunted me, calling me names like ‘negra,’ ‘baluga,’ even asking if my blood was also black,” Pinky says.

Like her siblings, Pinky is considered an ‘illegitimate’ since her mother refused to register her name under Edwards. They also found out that their mother used different aliases in their birth certificates. Only when two of her siblings went abroad, and her mother also became an overseas worker, that they were able to know her real name. She is Maria Oliva Daet.

Among the seven children, only one was able to go to the United States with his father. The Filipino sibling died in an illness when he was 17.

“My mother asked a father to bring one brother the U.S. when the base closed down. He was only five years old then. He visited us once. But we lost touch,” says Pinky.

Pinky says that her mother tried to abort her, the reason, she says, why she is sickly.

Despite her sickness, Pinky was able to raise a family–five sons and one daughter. She is now a grandmother too. Maria Oliva, however, still refuses to talk to her, or help her get better.

‘Not American’

In 2008, Pinky applied for a U.S. Visa and was denied. She is not qualified for the Adult Derivative Citizenship because of her mother’s failure to include the name of Edwards as her father. Due to the absence of communication and ignorance of immigration rules, Edwards failed to apply for Pinky’s citizenship before she turned 21.

A letter from the U.S. Consulate to Edwards said:

The petition in Superior Court should have occurred before her 21st birthday. Petitioning her now could no longer constitute legitimation since she already reached the age of 21. If you want to undergo DNA test to prove that she is your daughter, you may do so. However, positive results of DNA would not help resolve the legal issues between you and Pinky, for purposes of derivative citizenship.

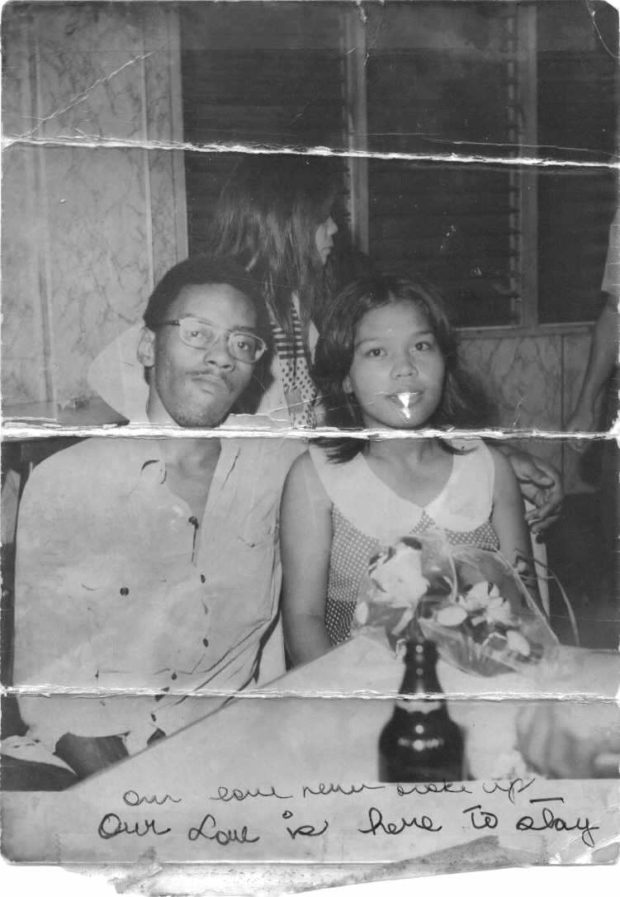

Jimmy Edwards and Merlie in 1974. CONTRIBUTED

Further, the letter said that under the Philippine law, Pinky is an illegitimate child since Edwards and Daet were never married. Under the U.S. law, Edwards did not meet the legitimation requirement of the state of North Carolina, his legal residence after Pinky’s birth and before her 21st birthday. In the state of North Carolina legitimation occurs only if the father files a petition before the Superior Court of North Carolina.

Edwards feels that US Immigration is unfair in dealing with the Amerasians’ claim for citizenship.

“Did you know a U.S. citizen father that has a child out of wedlock in a foreign country can’t automatically transmit U.S. citizenship to his child? I have a daughter, her husband, and six grandchildren that will probably never see the land of their father and grandfather,” Edwards laments.

Edwards also expresses his sadness for not being able to help Pinky. On her part, Pinky understands her father is a retiree and has his own family.

Pinky is still undergoing dialysis. Father and daughter are not giving up hope of being reunited.

If you wish to send help to Pinky Yabut in the Philippines please contact her at +63 9473911824 and home address at Blk 17 Narra Street, Lower Gordon Heights, Olongapo City.

A gofund me account was also set up for her dialysis: https://www.gofundme.com/pinky039s-medical-fund