U.S.-China trade war: What’s behind it, who will be hurt?

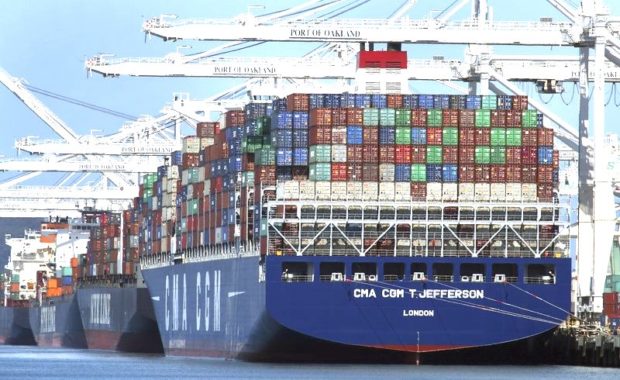

In this May 21, 2018 file photo container ships are unloaded at the Port of Oakland in Oakland, Calif. Barring a last-minute breakthrough, the Trump administration on Friday, July 6, will start imposing tariffs on $34 billion in Chinese imports. And China will promptly strike back with tariffs on an equal amount of U.S. exports. AP PHOTO

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump has boldly declared that trade wars are easy to win. He’s about to find out.

The Trump administration on Friday was scheduled to start imposing tariffs on $34 billion in Chinese imports. And China has promised to promptly strike back with tariffs on an equal amount of U.S. exports.

And just like that, a high-risk trade war between the world’s two biggest economies begins — one that could quickly escalate.

“I see us running into a full collision course in a few days,” said Ashley Craig, a trade lawyer at Venable LLP. “It seems as if both sides are fairly dug in.”

WHAT IS THE U.S. DOING?

The White House last month announced plans to slap 25 percent tariffs on roughly 1,100 goods imported from China, worth $50 billion a year. It had originally proposed the tariffs in April, starting with 1,333 Chinese products. After receiving public feedback, the administration cut 515 imports from the blacklist and added 284 others.

Starting Friday, the U.S. is taxing 818 Chinese products, worth $34 billion a year, from the original list. It won’t target the 284 additions, worth $16 billion, until it gathers further public comments.

___

HOW IS CHINA RESPONDING?

China has warned that it won’t yield to Trump’s pressure. Once the U.S. starts taxing Chinese imports Friday, Beijing has said it will impose 25 percent tariffs on 545 U.S. products worth $34 billion a year — from soybeans and lobsters to sport-utility vehicles and whiskey. China is considering a follow-up tariff on an additional 114 U.S. goods, worth $16 billion a year.

Beijing’s target list of U.S. goods to penalize is heavy on agriculture. That’s hardly a coincidence. Its tariffs are meant to deliver pain to American farmers, who overwhelmingly backed Trump in the 2016 election and whose interests are represented by powerful lobbyists and members of Congress.

In this April 5, 2018, file photo Terry Morrison of Earlham, Iowa, watches as soybeans are loaded into his trailer at the Heartland Co-op, in Redfield, Iowa. If the U.S. starts taxing Chinese imports Friday, July 6, 2018, Beijing plans to impose 25 percent tariffs on 545 U.S. products worth $34 billion a year, from soybeans and lobsters to sport-utility vehicles and whiskey. AP PHOTO

In the meantime, Trump has told his U.S. trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, to identify an additional $200 billion in Chinese goods for 10 percent tariffs. These penalties would take effect, Trump has said, if Beijing fails to reform its trade practices and proceeds with retaliatory tariffs.

The stakes could rise further yet: Trump has threatened tariffs on still another $200 billion in Chinese products if Beijing continues to retaliate.

___

WHAT’S BEHIND THE U.S.-CHINA RIFT?

The Trump administration has accused China of using predatory tactics in a lawless drive to overtake America’s technological supremacy. U.S. officials point to Beijing’s long-range development plan, “Made in China 2025,” which calls for creating powerful Chinese entities in such areas as information technology, robotics, aerospace equipment, electric vehicles and biopharmaceuticals.

Foreign business groups argue that “Made in China 2025” is unfairly forcing them to the sidelines in those industries. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative concluded after an investigation that China’s tactics range from requiring U.S. and other foreign companies to hand over technology in return for access to the vast Chinese market to outright cyber-theft. The U.S. also asserts that Beijing uses state money to buy American technology at prices unaffordable for private companies.

In May, the White House had said it would announce curbs on Chinese investment in U.S. technology by June 30 and impose those restrictions shortly thereafter. But it has dropped that plan.

___

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE INVESTMENT RESTRICTIONS?

The administration settled on a less draconian plan: It would back an effort in Congress to strengthen reviews of foreign investment under the existing Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS. This committee, led by the Treasury secretary, considers whether a foreign investment poses a risk to America’s national security. These reviews apply to all countries — not just China — and are conducted on a case-by-case basis.

The House has approved a bill to strengthen the CFIUS law, and the bill will likely be considered by a House-Senate conference committee for a Senate-approved defense measure.

___

WHAT’S THE LIKELY IMPACT FROM A U.S.-CHINA TRADE WAR?

The initial fusillade of tariffs will likely do little damage to the United States, China or the global economy. But if they escalate, the pain will deepen and spread.

Economists at Bank of America Merrill Lynch have warned that a full-fledged trade war, especially one that lasts more than a year, would slow the U.S. economy. By disrupting supply chains, eroding business confidence and heightening uncertainty, a trade war, they say, could “push the economy toward full-blown recession” and jeopardize America’s economic expansion — the second-longest on record.

Many individual businesses could soon endure hardship, too. Consider American soybean farmers, who send about 60 percent of their exports to China. Their shipments will now be subject to a 25 percent tariff, which will instantly make their crops far costlier in China.

What’s more, the U.S. tariffs on imported Chinese products could end up hurting American manufacturers. The Peterson Institute for International Economics calculates that 85 percent of the Chinese products to be hit by the initial Trump tariffs are machinery and components used in finished goods made in the United States. A result is that U.S. manufacturers will have to pay more for parts and equipment, thereby putting them at a competitive disadvantage to foreign rivals.

___

ISN’T THE U.S. ALSO SPARRING WITH OTHER TRADING PARTNERS?

Yes. Trump is battling in just about every direction. He has slapped tariffs on imported steel and aluminum — action that has drawn retaliatory tariffs from U.S. allies like Canada, Mexico and the European Union. The president is also threatening to impose tariffs on imported vehicles and auto parts on the grounds that they pose a threat to America’s national security.

And he is pressuring Canada and Mexico to agree to rewrite the North American Free Trade Agreement to shift more auto production to the United States and encourage companies to move investment from Mexico to the United States.

By brawling with America’s friends, critics say, Trump has squandered an opportunity to build a united front against China. After all, Europe, Japan and other rich countries have the same complaints about Chinese trade practices that America does.

___

IS THERE ANY REASON TO EXPECT A RESOLUTION?

Maybe. For a time, it looked as though peace might be at hand. In May, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declared the trade war “on hold.” The Trump administration suspended its tariffs after Beijing agreed to increase its purchases of U.S. goods, especially in agriculture and energy. The idea was that China’s additional purchases would shrink its trade surplus with the United States. Yet the cease-fire was short-lived. Critics dismissed Beijing’s commitments as vague, and Trump decided to proceed with the tariffs after all.

The top White House economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, has said the two countries are “in communication” — although there’s been no word of any formal negotiations. Trump himself told Fox News Channel’s “Sunday Morning Futures With Maria Bartiromo” that “China wants to make a deal, and so do I, but it’s got to be a fair deal for this country.”

____

HAVE THERE BEEN TRADE WARS BEFORE?

You’d have to go back to the 1930s to find anything close to the hostility between the U.S. and its top trading partners right now. During the Great Depression, many countries, including the United States, closed their markets to imports. A plunge in global trade likely worsened the Depression.

Many less intense trade conflicts have followed. President Ronald Reagan slapped tariffs on $300 million worth of Japanese imports in a dispute over the semiconductor industry and strong-armed Tokyo into accepting limits on car shipments to the United States.

In 2002, President George W. Bush imposed tariffs on Chinese steel. The move allowed U.S. steel producers to increase prices, raising costs for companies that buy steel and pressuring them to cut back elsewhere. But the tariffs are thought to have cost significant U.S. job losses.

In 2009, the Obama administration imposed tariffs on Chinese tires, charging that a surge in imports was hurting the U.S. tire industry. Beijing counterpunched. It imposed a tax of up to 105 percent on U.S. chicken feet — a throwaway item in the U.S. that’s considered a delicacy in China. The Peterson Institute for International Economics calculated that the tariffs probably saved 1,200 American tire jobs. But consumers paid over $900,000 in higher tire prices for each job saved.