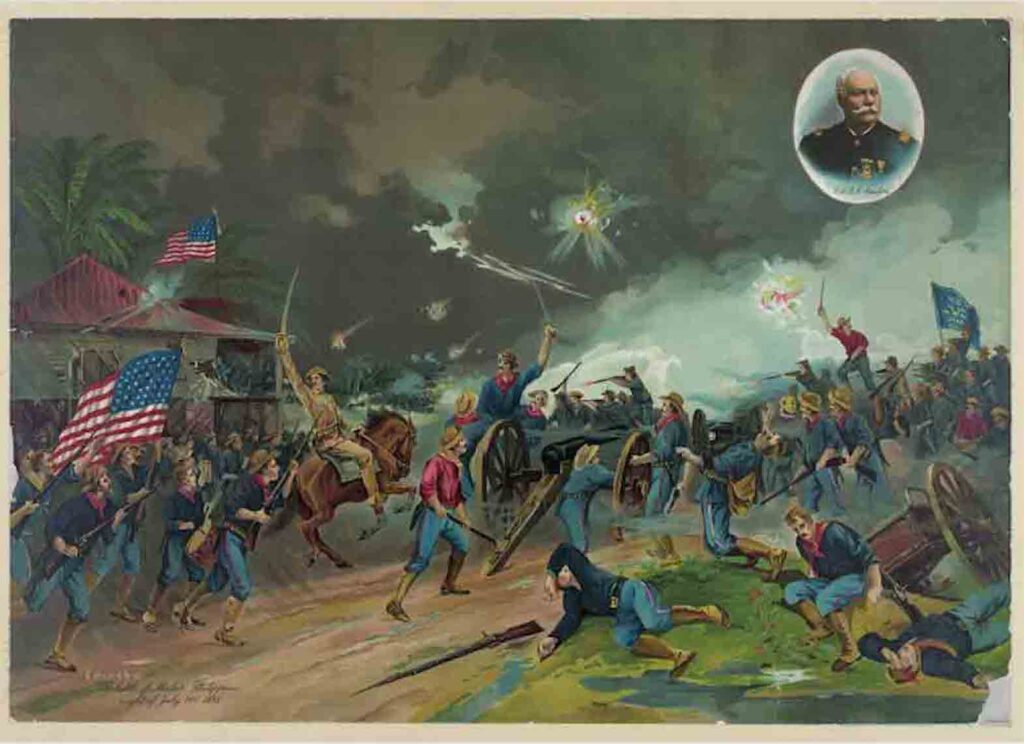

Little-known Battle of Malate, July 31, 1898

The battle between US and Spanish forces was brief but intense, with deaths and wounded soldiers on both sides.

By the end of July 1898, the Spanish-American War in the Philippines was reaching its apex. Emilio Aguinaldo’s forces were suffocating the Spanish military and civilians with siege lines surrounding Manila. The trapped and cut-off Spanish lacked a steady supply of food and water. The Philippine rebels were maintaining an upper hand on the ground around Manila and on Luzon.

At the end of July 1898, the United States Navy still controlled Manila Bay. Admiral George Dewey had received good news that the Spanish fleet in Santiago, Cuba had been destroyed by the U.S. Navy. Following the American victory in Cuba, the Spanish Flying Relief Column sailing to Manila under the command of Admiral Manuel de la Camara was abruptly recalled to Spain on July 7, 1898. The Spanish naval threat to the Americans and Filipinos was over.

The American ground troops, under the command of Major General Wesley Merritt, were slowly making their way from San Francisco to Manila. By the end of July 1898, the American ground forces in the Philippines totaled 10,464 soldiers and 470 officers. The Spanish still had a numerical advantage of 20,000 soldiers, but the combined American and Filipino soldiers totaled approximately 32,000.

You may also like: 1898, the year of dramatic changes for Spain, PH and US

The problem with the combined American and Filipino ground troops was that the Americans were not communicating with the Filipino rebels. The Americans were also not conducting operational planning with the Filipinos. Emilio Aguinaldo and his forces were supposed to be an American ally. Without a joint effort by the Americans and Filipinos against the Spanish, the numerical advantage was irrelevant.

Unfortunately, Merritt considered Aguinaldo as his subordinate and not as an equal. Major General Merritt was upset that Aguinaldo did not report to him when the American general arrived in Manila. Merritt did not want to negotiate directly with Aguinaldo until Manila was under American control.

Regardless of Merritt’s arrogance, he still needed the Filipino rebels. Aguinaldo had complete control over the siege lines encompassing Manila. If the Americans wanted a piece of the entrenchments facing the Spanish, they would have to negotiate with Aguinaldo.

Once again, Merritt irritated and slighted his ally. He refused to meet personally with Aguinaldo. Instead, Aguinaldo was forced to meet with Merritt’s subordinate, Brigadier General Francis Greene. During the discussions between Greene and Aguinaldo, the Americans only acquired a small section of the siege lines.

In fact, the American portion of the massive Filipino lines surrounding Manila was only 1,000 yards. The American lines were directly south of Malate. The American lines began at the beach on Manila Bay and extended to an area called Estero de Tripa de Gallina. The American forces directly faced a Spanish fort called Fort San Antonio de Abad.

Once the American soldiers replaced the Filipino rebels at this section of the lines, Admiral Dewey’s ships in the bay fired a few rounds at the fort to inform the Spanish of the American resolve in its ground troops.

The American soldiers started performing rotating duty from Camp Dewey, a few miles south of the lines, to the newly granted entrenchments. The soldiers used shovels and picks to expand and improve their lines. Their rifles and artillery were always close by in case of an attack by the Spanish.

The surprise attack by the Spanish came on July 31, 1898, at 11:10 p.m.. The 10th Pennsylvania Volunteers and the 1stCalifornia Volunteers were at the point of the attack. The American volunteers had never been in combat previously. The soldiers quickly discarded their picks and shovels and picked up their rifles.

They had to endure over three hours of intense rifle and artillery fire. The Americans did receive reinforcements from Camp Dewey quickly. Although the Americans were rookies in combat, the soldiers were able to hold their lines. Unfortunately, ten Americans died, and thirty-three were wounded during the battle. The Spanish proved that they still had some fight in them.

One could question why the Spanish attempted this battle when their situation in the Philippines was bleak and precarious. The Spanish knew that Aguinaldo’s forces surrounding Manila were strong and dangerous, but they did not know the how the American volunteers would respond in combat. During the battle, the Americans did not panic and did not run away The American soldiers stood their ground. The Spanish days in the Philippines were now numbered.

The fighting on July 31, 1898, has been classified as “The Battle of Malate.” The battle was brief but intense, with deaths and wounded soldiers on both sides. This battle was an obscure event in Philippine-American history during the Spanish-American War, and most Americans and Filipinos have never heard of the battle.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is Public Historian and a former park ranger in interpretation for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. He can be contacted at: flakedennis@gmail.com