Southern California trying to make rain water safe for the ocean

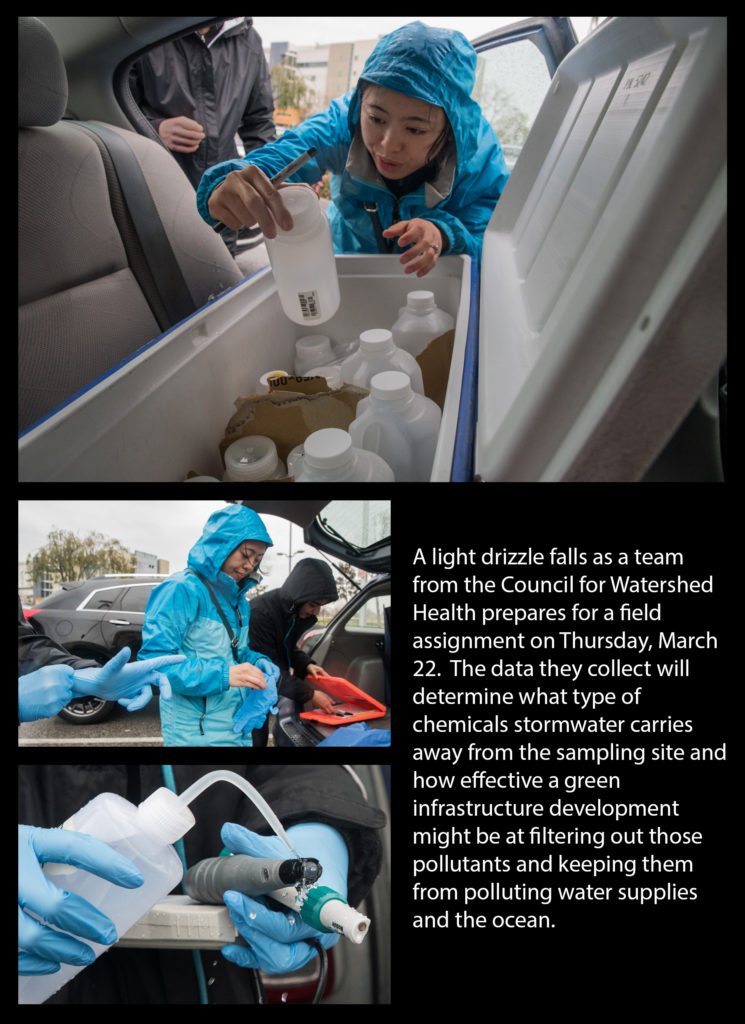

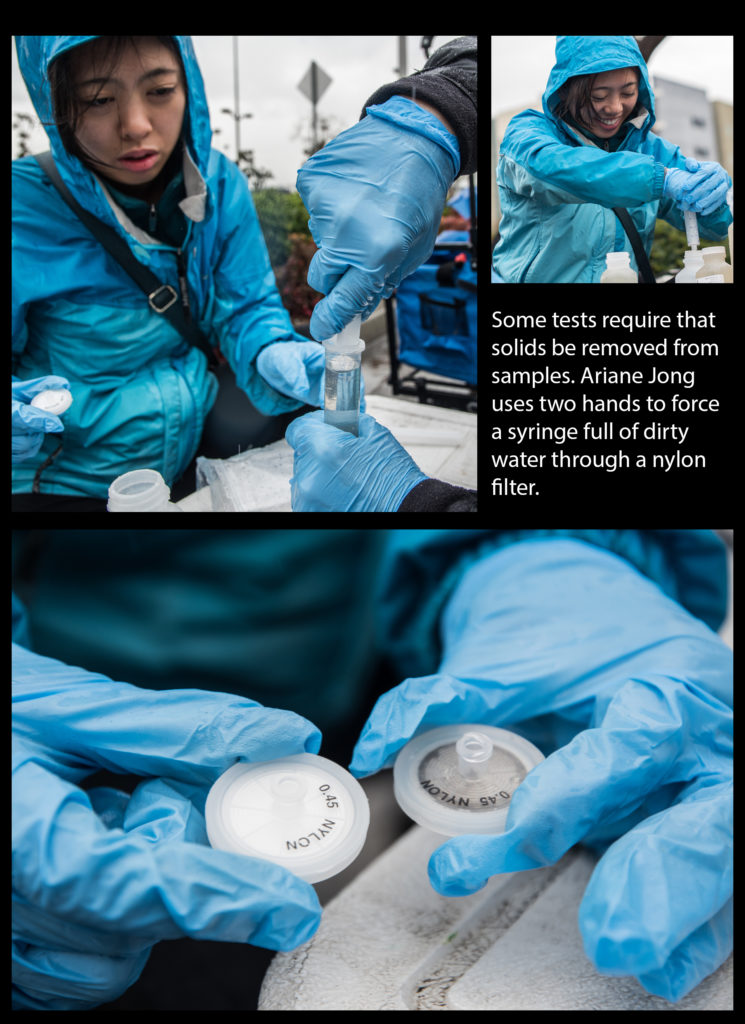

LOS ANGELES — A storm had just passed overhead without incident, sparing Southern Californians from a second round of disastrous mudslides. In a puddled parking lot in El Monte, Ariane Jong stashed away a pair of rain boots and soggy coveralls in her backseat, next to a cooler full of samples that she and her team had collected beneath a pounding torrent. Finally dry but drained and hungry, she stepped into Ramen Ichiraku and joined the others at their table.

The air was warm inside the tiny restaurant with walls decorated in red, black, yellow, and orange by murals and toys. Faint steam and the scent of savory broth wafted up from freshly served bowls, halting conversation. A good end to a good day of bad weather.

“I think the strangest thing about today was how well everything went,” said Jong, a staff scientist for the Council for Watershed Health (CWH), as her waiter packed away leftover stewed pork ramen. The sound of plastic bag handles crinkled into a knot was heard over the muted pitter patter of a drizzle beating on car hoods and pavement outside.

Rain happens infrequently in Los Angeles County, but occasionally falls with an intensity that can wreak havoc. At the very least, rain snarls commutes and deposits the oil and garbage that accumulate on the County’s roads, highways, and sidewalks into the Pacific Ocean.

At their worst, extreme downpours and the flooding that results can wrench homes loose from their foundations and trap people and property in potentially lethal waves of water and mud.

Decades ago, the banks of the Los Angeles River swelled during what meteorologists called a 50-year storm. Flooding led to over 100 deaths and caused $78 million in damage in March of 1938, which would amount to over $1.2 billion now, if adjusted for inflation.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the Army Corp of Engineers encased the river in cement, transforming it into the concrete channel that snakes through most of the county today.

Flood management measures taken 90 years ago proved effective in preventing the type of catastrophe LA experienced in the first half of the twentieth century. However, they did not account for storm water runoff pollution, restricted groundwater infiltration and other environmental concerns people in Southern California encounter today.

“Back then, yes, it did prevent flooding,” said Jong. “But 50 years from now who is to say, with the size of a storm like that being more frequent, that it would prevent flooding?”

She agrees with a growing body of evidence projecting that extended droughts punctuated by intense storms will get progressively worse if global temperatures continue to rise. Longer periods without rain could make water even scarcer in a County that currently gets 70 percent of its supply from outside sources.

Officials at the Department of Public Works hope to develop a holistic solution to LA’s water dependency with what they call the Safe Clean Water Program – LA. If approved, the initiative would install green infrastructure improvements like those monitored by CWH throughout the County to help capture and repurpose an additional 100 billion gallons of rain.

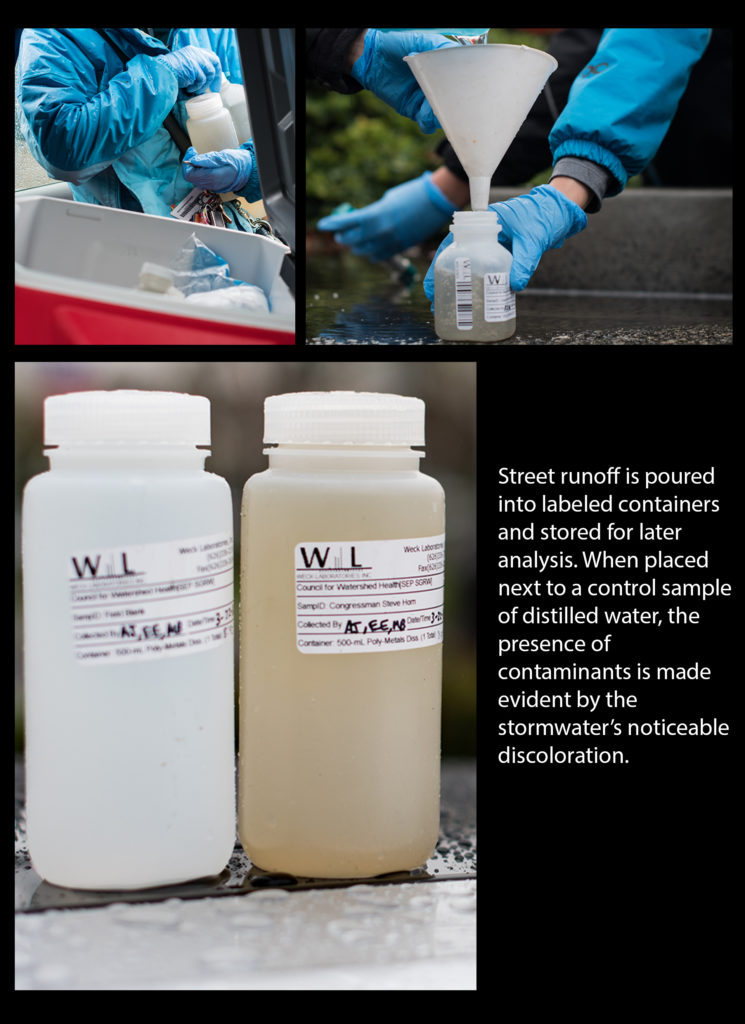

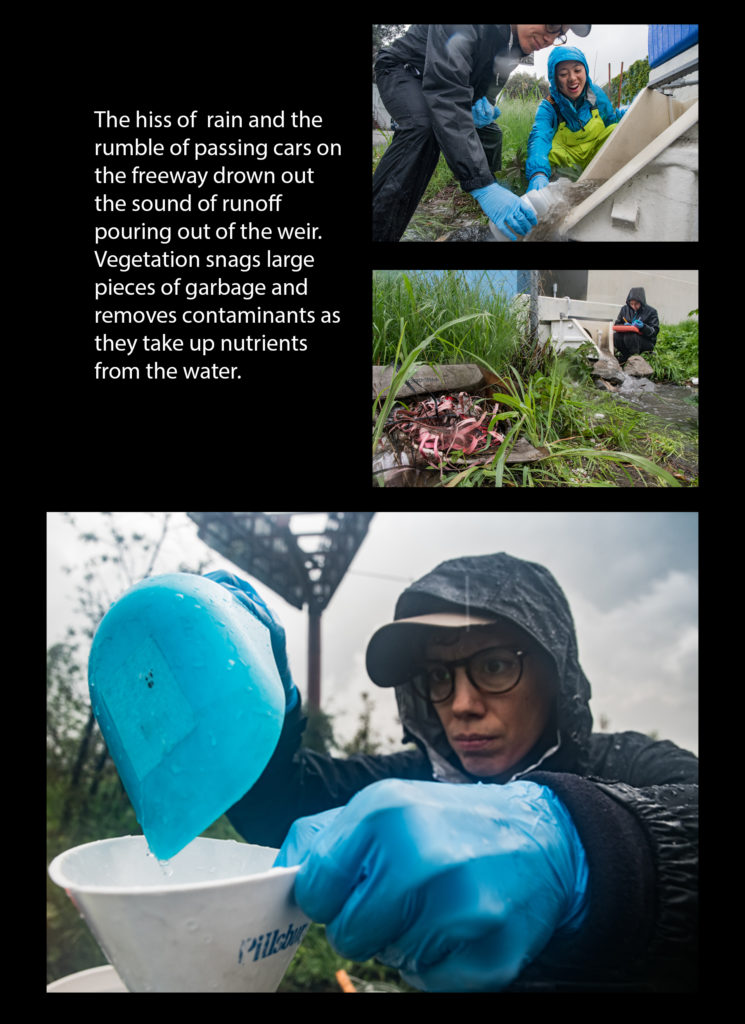

Green Infrastructure features mimic natural environments to mitigate flooding. They use vegetation to filter out debris and chemical contaminants while directing water over unpaved surfaces that allow it to seep into the earth. That stops polluted rain from reaching the ocean and allows it to rejoin local groundwater supplies.

These sites take on a variety of forms and sizes and can be as inconspicuous as a row of shrubs planted in the center divider of a suburban street or a rain park growing out of a previously vacant lot tucked beneath the shadow of a freeway overpass.

Efforts like the Safe Clean Water Program – LA are an example of a forward thinking, environmentally conscious approach to problem solving. Reintroducing green space into predominantly concrete landscapes might also serve as a reminder that cities are still part of the environment.

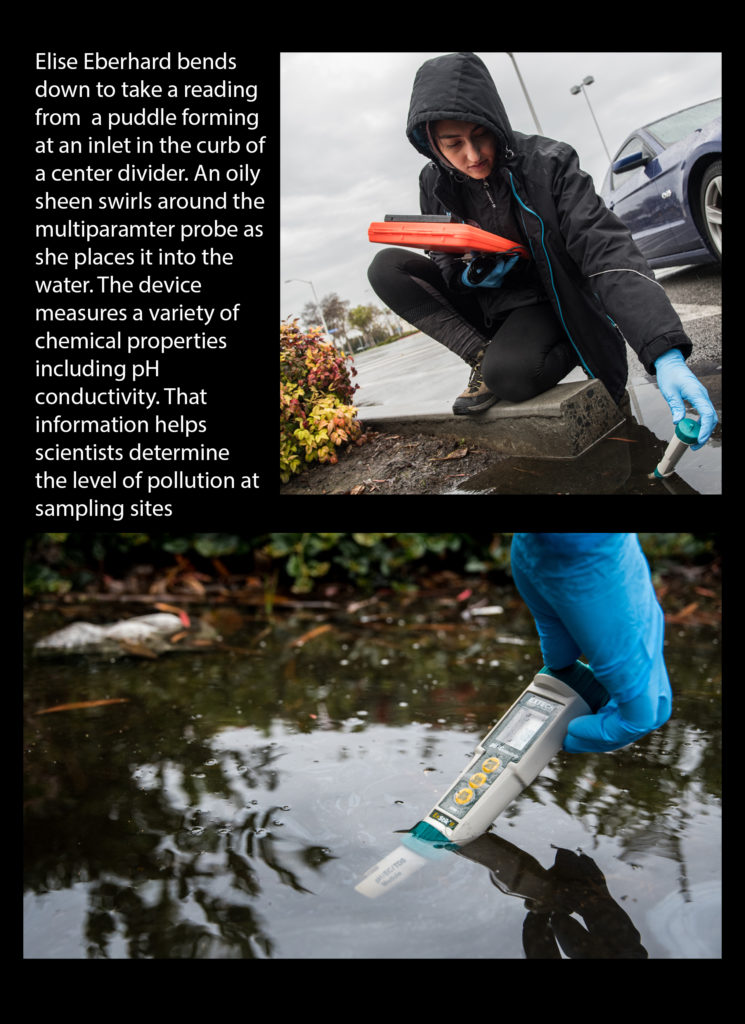

“There’s a separation between urban areas and nature,” said CWH Research Associate Elise Eberhard. “Even though we are in an Urban area, there is still wildlife and nature that we need to protect here.”