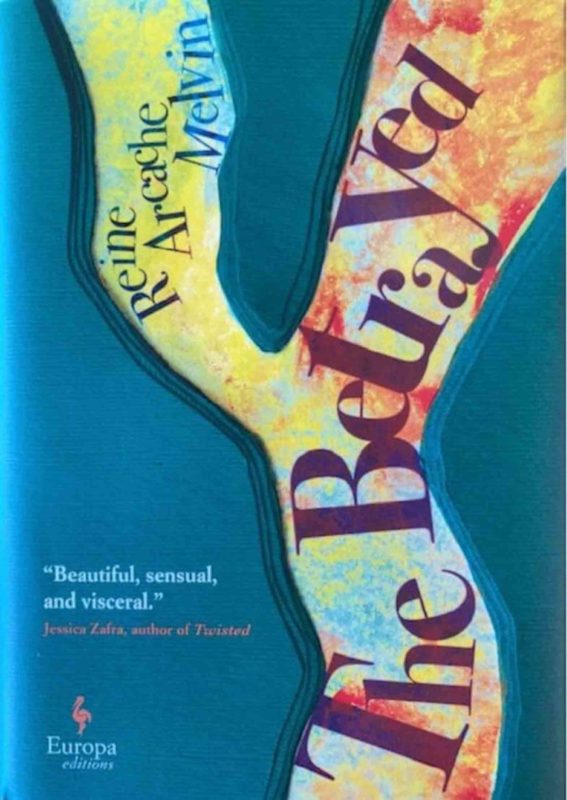

The Betrayed, Reine Marie Melvin, Europa Editions, 464 pp.

NEW YORK—Here is the continuation of my interview with the Paris-based Filipina writer Reine Marie Melvin, author of The Betrayed. The novel, centered on the lives of two sisters and the man they both love, offers a disturbing portrait of contemporary Philippine society, where the personal almost always trumps the political—a, if not the, major reason political parties come and go with predictable rapidity.

LHF: The complicated relationship between the sisters Lali and Pilar—daughters of the slain opposition figure—and between them and Arturo, the dictatorial General’s godson, constitutes a kind of menage à trois and seems to exemplify how personal fealty and boundaries within upper-class Philippine society constantly shift even when political and social strictures are firmly in place.

RMM: The sisters and Arturo all come from the same upper-class society, even though two of them have money and position while another has lost these, even though their families and loyalties are on opposite ends of the political spectrum—pro-dictator and anti-dictator. People in that circle tend to know the same people and go to the same schools, and are often related to each other by blood or marriage. I was interested in showing how class and power structures in the Philippines define so much of what people believe in, and how these remain largely intact to this day. Marcos was ousted, but the strongman figure remains popular, and now another Marcos is running the country. In the novel, Arturo is aligned with the dictator, but he rebuilds his political career after the dictator is kicked out—the old families protect their own. Business interests, political alliances, the old-school network, the intermarriage of the elites and family ties: all helped destroy the promise of the so-called revolution, and continue to impede real social and political change in the country.

LHF: The title The Betrayed raises the question, what and who are betrayed, and who does the betraying. There are levels of betrayal: of personal commitment, of a democratic society, of historical truth, etc. And there are the betrayers: coup plotters, corrupt politicians, warlords, unfaithful spouses, vigilante groups, businesses, etc. What made you choose this theme and did it suggest itself right away ?

RMM: For a long time, the working title was The Sisters, but the deeper theme of the novel is how most people mean to do good, or at least to do no harm, but they are living in a violent, damaged world and find themselves faced with terrible choices. Some of my characters are born into lives that are too big for their souls, and the historical and political circumstances—and their own weaknesses—drive them to betray each other, their country, and even the best part of themselves. And yet they are fundamentally decent people. There are so many layers of betrayal in the book, as you point out, so the title eventually imposed itself.

LHF: The American journalist David is an intriguing and enigmatic character, a reflective man who lives a monkish existence. Were you writing him against type, i.e., the brash, presumptuous, Western foreign correspondent who rarely bothers to look beneath the surface realities of whatever country he or she is covering?

RMM: I wanted to write about a well-meaning, intelligent man who creates havoc despite himself: in trying to report on violence, he creates more of it. David is an outsider who is sincerely curious and reflective about the Philippines, but the danger is that he thinks he understands the country: he does try hard to look beyond the surface realities, but he imposes his interpretations on an extremely complex, often contradictory situation and people. And Lali has a revelation about him at some point: David wants to document the violence in the country because violence excites him—and because he doesn’t have to live with it. He can fly into the Philippines and fly out whenever he wants, unlike people like Lali and Pilar and Arturo, who are stuck inside and must make compromises to survive. He infuriates Lali with his moralistic judgments toward her and the Philippines, especially because he has never been in danger himself. Also, David has a half-Filipina mother, so although he looks and acts very American, he is a Fil-Am who is looking for a way back into the Philippines. David, Lali, Pilar and Arturo are all flawed characters who aim high and mean well, but what hell they create around them.

LHF: Could you talk a bit about how having lived in Paris now for several decades has shaped both your writing and your views of Philippine society?

RMM: I’ve lived in Paris for decades, but for so long, perhaps too long, my heart and thoughts and passions have remained rooted in the Philippines. My library is full of books about the Philippines. Paris always felt like a transient place for me, a place where I could disappear. I will always be a stranger here. Now I want to try and write stories set in France, as I tell myself it’s time to let go of Manila, that I’ve been gone too long and no longer hear the stories and the silences there, but I am not sure there’ll be anything to say.

LHF: You finished the novel a few years prior to this year’s presidential elections, with the Europa edition being released just when the Marcoses have returned to power. As you were working on the novel, did you ever foresee this happening?

RMM: I didn’t foresee Marcos Jr. being elected president, but the novel does talk about how the same families keep getting elected into office, how political dynasties are entrenched in the country. Also, and this was unconscious (yes), the Arturo character was initially called Bong, and he is pushed into politics by an ambitious mother who wants to salvage the family’s reputation and fortunes. There are many Bongbongs and Arturos in the Philippines, as we know.