The March for Our Lives protest, which drew more than a million young Americans and their supporters, is an important reminder for Filipinos in the Duterte era: fighting for justice means mobilizing huge numbers of people in the streets.

It means mass demonstrations, not in cyberspace or in social media, but in the real world.

It means getting people to turn away from their mobile phones and laptops and to get directly involved in communities, factories, campuses.

Yes, the young activists behind March for Our Lives used Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other social media platforms to organize, rally supporters, and publicize the event.

The “likes,” the “shares” and the “comments” all helped boost their engagement stats and helped them reach more people. But ultimately, they succeeded in the most important aspect their struggle: getting people to go out into the streets.

That’s an important point to stress as supporters of Duterte and his emerging fascist order flaunt their dominant, loud, often obscene and obnoxious presence in social media.

March for Our Lives took place just weeks before the 40th anniversary of another historic protest that’s worth remembering — and celebrating.

On April 6, 197f8, the entire Metro Manila erupted in noise, in a collective act of defiance against another fascist regime.

That evening, people throughout the capital cheered and yelled, banged pots and pans, honked their horns and openly spoke out against the Marcos dictatorship. (This report on YouTube offers a glimpse of that historic protest.)

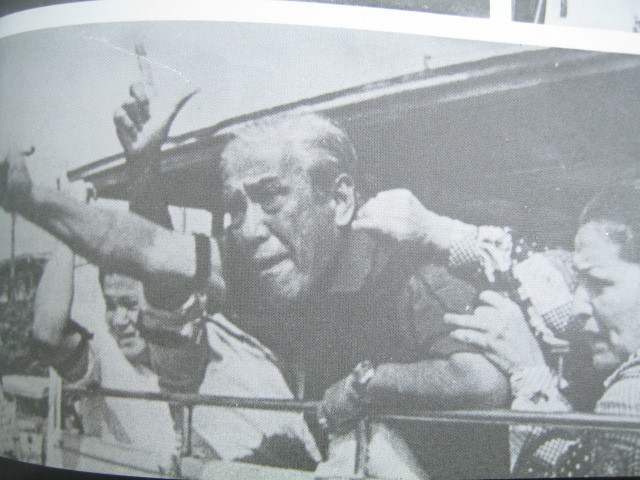

This was during the Batasang Pambansa elections when an opposition coalition that included Ninoy Aquino and Nene Pimentel, father of Duterte-ally and Senate President Koko Pimentel, launched a bold and seemingly Quixotic electoral challenge against the Marcos dictatorship.

They knew the elections would be rigged and they would lose. But they knew it was an opportunity to speak out against the regime.

A high point of the Laban campaign was the April 6 Noise Barrage. As the narrator in the YouTube clip of that night said: “The regime was stunned by a new form of protest: the noise barrage. … In the six years of martial law, it was the first time that such a boisterous protest exploded in Metro Manila.”

Now, it’s important to understand the context of the 1978 Noise Barrage. The elections were meant to deceive the world into believing that the Philippines under Marcos was a democracy.

But the country was then a police state. Marcos was then at the height of his power, having padlocked Congress, cracked down hard on media and jailed most of his critics and opponents.

In many ways, launching the 1978 Noise Barrage seemed like a stupid and even dangerous idea.

Remember this was before Facebook, Twitter and Google. People didn’t use cell phones or computers. To organize any kind of mass action meant making phone calls or face-to-face meetings to let people know about when and where a demonstration was going to take place.

It was also a time of intense repression. Even the mildest forms of opposition could mean harassment or arrest. In some cases, it even led to death.

That’s what made the 1978 Noise Barrage a stunning victory of Filipino activism during the Marcos regime.

I was only 13 when, for a few hours in April 1978, Metro Manila seemed to speak in one loud, defiant voice.

The dictatorship cracked down hard after the elections. But many Filipinos, including many from my generation, never forgot the thrill of that short-lived victory on April 6, 1978. Eight years later, many of us would join the final confrontation with the tyrant.

Visit the Kuwento page on Facebook.