Human rights lawyer Chel Diokno

(10th in a series of profiles of Martial Law Babies, the generation Marcos tried and failed to mold into his version of the Hitler Youth. They fought his dictatorship instead.)

Chel Diokno was only 11 years old when his family’s world was turned upside down. One night in September 1972, soldiers came to their home in Magallanes and told his father, Senator Jose Diokno, that he had to come with them.

“We’re here to invite you,” the military officer in charge of the team said, Chel recalled.

“Magalang naman siya. He was polite,” he said. “I remember my father saying, ‘Is this an invitation I can refuse?’” No, the colonel said. ‘I’m sorry sir. But you have to come with us.”

The respect the military officer showed his father was not surprising. Senator Diokno was a well-regarded public figure, and the Dioknos were a prominent family.

That changed after his father’s arrest, after Ferdinand Marcos grabbed power by imposing martial law.

“Parang bumaligtad yong mundo namin,” Chel said. “It was like our world got overturned.”

“My dad was a senator. He was a lawyer. We never thought that he could be taken away from us in that manner. There was no legal reason to put him in jail. That really was very traumatic. It was the first time na natikman namin ang mapait na lasa nng inhustisya. It was the first time we tasted the bitter taste of injustice. We were thinking. ‘If they could do that to my father, then they can do that to anyone.’ And in fact, that’s what happened.”

***

The respect and politeness shown by Senator Diokno’s military captors was eventually replaced by crass, even cruel treatment from a military now under Marcos’ control.

Visiting his dad in prison was challenging. At times, it became excruciating. The military imposed arbitrary rules that were sometimes unreasonable and mean-spirited. “Sometimes they would tell us you can visit every day and when we would go there they would say, ‘Sorry, no visits today.’ The low point was when we were suddenly denied visits.”

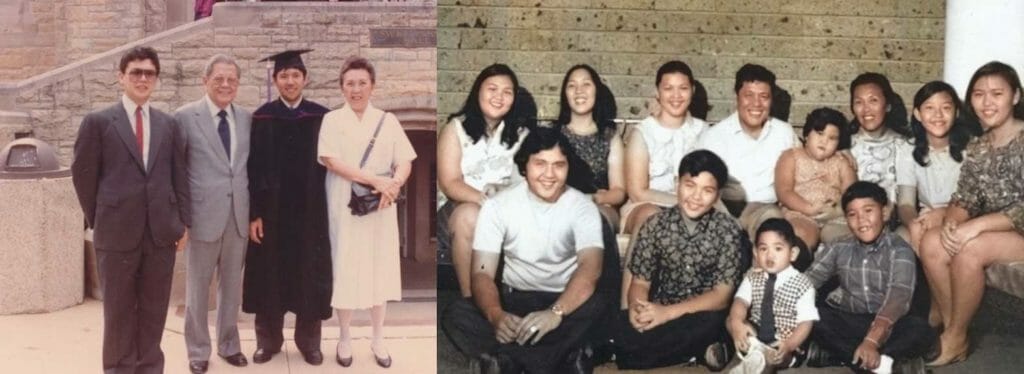

Chel Diokno, with his parents, graduating from law school in the U.S. (RIGHT): With the Diokno brood. FAMILY PHOTO

It got worse. One morning, the military arrived at their home to return Senator Diokno’s belongings.

“Why are you bringing these here,” Nena Diokno, Chel’s mom, asked the soldiers. “Nasaan ang asawa ko? Where is my husband?”

“We had no idea where he was,” Chel recalled. “They didn’t say anything. They just put everything down in the garage and left.”

The reason for the visit became clear soon enough. The Marcos military had transferred Pepe Diokno, together with Ninoy Aquino, to another military prison at Fort Magsaysay in Nueva Ecija.

“When we saw him it was again very traumatic. We couldn’t even touch [him]. There were two layers of barbed wire between us. He looked very pale and gaunt. He had obviously lost a lot of weight and he was holding on to his pants. “If I let go of my pants mahuhulog ang pantalon ko. My pants will fall,” he said. “We were all very emotional umiiyak kami lahat.”

“Iyon siguro ang pinaka low point. That was probably the lowest point,” Chel said.

*******

Pepe Diokno was eventually released in 1974. The dictatorship demanded that he report on a regular basis to Marcos’ military and he was required to provide a recording or a transcript of any speech he gave.

But Ka Pepe, as the senator was fondly called, was not going to be silenced. His release began a new chapter in his political career, and for Chel and the Diokno family.

“It was an awakening,” he said. Before his father’s arrest, the Dioknos were exposed mainly to the world of the elite. “Before he was arrested, the people that would usually come visit the house would be other senators, other politicians, most of the time coming in expensive cars and expensive clothes,” Chel recalled.

That changed after Pepe Diokno’s release when he became deeply involved in the fight against the Marcos dictatorship — a struggle that was being waged by workers, students, farmers, church workers and the urban poor. The Dioknos moved from Magallanes to a house in New Manila, Quezon City, which became a center of activism against the dictatorship.

“The people that would come to the house would be karamihan ay mga naka-tsinelas na. Most of them were in slippers. You have priests and nuns coming in pretty much every day, students, workers. We were exposed to them. And that really opened our eyes to what was happening.”

Pepe Diokno launched the Free Legal Assistance Group, or FLAG, which quickly emerged as a leading advocacy organization defending Filipinos against the regime. It was around that time that Chel decided he was also going to be a lawyer. Ka Pepe would show him how to become a good one.

“Whenever I would see him dressing up for court, I would ask him if I could go with him. I would dress up in a polo barong, carry his bag. On several occasions, I was even allowed to sit at the counsel’s table. I never got bored. The trials were really fascinating.”

The trials were “really moro-moro (for show),” Chel said. But they “became a way for the people involved to bring out really what happened.” “The cross examinations were fantastic. Doon talaga lumalabas yong cover up or if the evidence was planted. That was when coverups were exposed. It was very exciting. Kung minsan talagang napapahiya ang mga witnesses for the government. Sometimes, government witnesses found themselves embarrassed.”

Chel worked for his dad during summers, helping him prepare for his cases. “I learned so much about preparing a case during those times more than I ever did in law school.”

It was not an easy time for the Dioknos and the entire country. “Of course the anger and the frustration was there every single day. We were still being monitored and subjected to surveillance. The anger was also how they managed to destroy our democracy and take away our freedoms.”

The early years of martial law had been particularly hard and frustrating, marked by the “feeling that you were alone,” Chel said.

“Takot lahat. People were scared. Nobody wanted to speak up.” But by the time Ka Pepe was released and building FLAG, people were also starting to fight back. From only about four lawyers, FLAG grew to more than 100 lawyers nationwide. Unlike the initial years of the dictatorship, Chel said, “they weren’t like voices in the wilderness fighting the government.”

******

And the voices kept getting louder. They grew stronger following the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983. Pepe Diokno emerged as one of the most inspiring figures in the fight against the regime which was eventually overthrown in the 1986 uprising.

Chel had left to study law in the U.S. in 1983. By the time he returned home in 1986, the dictator had fallen. By then, Pepe Diokno was ailing. He died in February 1987.

He left behind a powerful legacy. Pepe Diokno helped build a movement and culture based on respect for human rights. By the time he began practicing law, Chel knew he wanted to continue and build on his father’s work. “From the time I became a lawyer in 1989, I’ve been a human rights defender and a teacher.”

Chel taught law at De La Salle and became founding dean of the university’s newly-established law school which opened in 2010. He also did the job that he had been preparing for with the help of his father since he was a young boy: defending and advocating for victims of human rights abuses.

******************

Human rights violations were still a problem for law enforcement and military agencies that never really underwent serious reforms and never came to terms with what happened under Marcos.

But things were improving, Chel said. One key reason was one of Pepe Diokno’s biggest contributions, the creation of the Commission on Human Rights. Many military leaders also showed willingness to work with human rights lawyers and advocates to find ways to instill a stronger human rights consciousness within the military.

“I was very happy where I was in my life and where the human rights situation was,” Chel said. “By 2015, we would even be invited by the armed forces and the Philippine National Police to conduct training. Things were looking very bright and there were so many laws already being passed. We felt that we were really going in the right direction.”

But then another storm hit. “When 2016 came around, all of that simply collapsed,” he said.

That was the year Rodrigo Duterte was elected president. He immediately unleashed a massive campaign supposedly against illegal drugs but which turned out to be a brutal onslaught against human rights. Suddenly, under Duterte, human rights became a dirty phrase, dismissed and even denigrated by Duterte himself.

“The concept of human rights was demeaned by no less than the highest executive officer in our country. And of course that was when the killings began every day.”

A few weeks after the Duterte Killings began, Chel began speaking out against the brutality. “I just woke up one Sunday and said I can’t abide by this and remain silent. So I wrote something and posted it on Facebook and made it a public post.”

“Sabi ko hindi na ako pwedeng tumahimik sa ganito. I could not keep silent. I couldn’t abide by the fact that all our democratic institutions were attacked, and that not many people were opposing it. Hindi ako papayag na my kids are going to grow up in a place like this. I have to fight. There’s no choice.”

****************

Chel had proudly embraced his father’s path as a warrior for human rights. But even though he was the son of a prominent and even revered political figure, he had never thought of entering politics. “I never had any political ambitions. I had been offered the run ten, fifteen years ago and I declined all of that.”

The brazen disregard for human rights under Duterte, and the destruction of a culture for human rights that his father and many others worked for made him reconsider.

In his late 50s, Chel realized that it was no longer enough to lead a life as a teacher, academic and human rights lawyer. In 2019, he joined the opposition ticket Otso Deretso. Not one of the opposition candidates won. But Chel was prepared for that.

“I had no illusions of winning,” he said. But joining the campaign was “a way of being able to reach more people with what I want to say.” He got about six million votes, which he found surprising. This year, he joined the Leni Robredo campaign and again lost. But Chel got even more votes than three years ago.

**************************

Bongbong’s election, the Marcos’s return to power, was an expected but still jarring development for many of us who lived through the dark years of dictatorship. It’s especially disconcerting and demoralizing for Martial Law Babies like Chel and myself.

I began this series at the start of the year before the dictator’s son claimed victory. I had meaningful conversations with former fellow activists and friends — the feminist leader Jean Enriquez, climate activist Lidy Alejandro, human rights lawyers Raffy Aquino and Ted Te, Senators Risa Hontiveros and Kiko Pangilinan, Congressman Erin Tanada, international relief advocate Jade Pena, and social entrepreneurship advocate Lisa Dacanay.

Chel was the first martial law baby I interviewed after the election — and the last for this series. In some ways, it was also the conversation that helped me understand what our generation went through — and what the nation now faces in this new political order.

*****************

Politics is now an arena where Chel is prepared and willing to engage.

Suddenly, the young boy who watched his father unjustly prisoned and who served as his little assistant in courtroom battles to defend victims of the regime was taking a higher-profile role in a new fight.

It’s a challenging new era, now dominated by the dictator’s son who has routinely belittled and denied the atrocities during the Marcos dictatorship.

“It just makes us all the more determined to continue to speak the truth, the power and continue to explain to people what really happened during that dark period of our history. I view my role as someone who can speak the truth to power especially, especially with the young people. The hope of changing what’s happening is with the young people of today.”

One of Chel’s stories about his father’s imprisonment in Nueva Ecija underscores this optimism, and the perseverance and patience, courage and faith that helped many of us survive and even thrive during martial law.

Ka Pepe’s cell had a door that led to a yard overgrown with weeds and tallgrass, got permission to clear the area where he hoped to build a garden. “On Sundays, me and my brothers would bring shovels. He started to grow plants and trees. He tended to that until he was released.”

Fast forward about 20 years. Chel, who had just started practicing law, found himself working with a client who was detained “in the exact space where my dad had been detained.” Chel immediately realized this during one of his visits to his client, “As we were approaching, I said, ‘I know this place.’ When we entered the cell, I told my client, ‘This is where my dad was.’”

He saw the door that led to the garden. Before leaving the camp, he asked the guard if he could see the yard beyond it. “Puwede ko bang makita iyong nasa likod? Gusto ko lang malaman kung nandiyan pa iyong mga tinanim ng tatay ko. Would it be okay if I checked out the back? I just want to see if my father’s garden is still there. Lo and behold, when he opened the door, it was still a garden. It really amazed me that it lasted that long.”

When asked if he ever feels discouraged, Chel was quick to say, “No.”

“I get that question so often. I can’t explain why, but perhaps it’s because I interact with so many young people. They’re the ones who give me hope. That is really what keeps me going. I have never given it the thought that it’s a hopeless situation.”